Stonington, the state of Maine’s top fishing port in landed value, is facing seismic change. By mid-century, its lobster fishery could drop by 15 to 20 percent due to warming ocean waters, the Gulf of Maine Research Institute predicts.

Tethered to the mainland by a thin thread of causeway and an 80-year-old bridge, this small town also faces rising seas that threaten infrastructure – including the town pier and a waterfront fire station.

Kathleen Billings, Stonington’s town manager, knows that “worse stuff is coming.” Seven years ago, she began reviewing inundation maps, writing grants to assess the vulnerability of town infrastructure and setting aside funds.

“All these projects are really daunting, and you can’t just keep putting your mil rate up,” she says. “We’re maxed now as is.”

“All these projects are really daunting, and you can’t just keep putting your mil rate up,” she says. “We’re maxed now as is.”

Stonington has received state funds for planning and design, notes its economic development specialist Henry Teverow, but not for “physical infrastructure improvements. That’s where we need help the most.”

Climate hazards in Maine are placing an increasing strain on state and municipal budgets – reducing revenues, raising expenses and causing some economic shocks (such as price spikes in materials and food due to disruptions elsewhere). Yet little effort is being made to quantify the potential impacts.

Billings would like to see the state undertake some long-range financial planning that accounts for coming climate disruptions. She recounts a recent meeting with Maine Department of Transportation and emergency management agency staff to discuss the Deer Isle causeway, where water already overtops portions of the roadway at extreme high tides. Rocks in the roadbed never got fully rip-rapped decades ago and island residents are concerned about potential washouts.

“There should be some plans moving forward. It shouldn’t come to that,” Billings said, noting that Deer Isle contributed half a billion dollars to the state’s economy over the past decade.

Officials at that meeting told her causeway upgrades would be “super-expensive,” she says, adding, “It’s also super-expensive to lose your community or have people move off island.”

A Perfect Storm

Much of rural Maine is vulnerable to cascading economic impacts as climate disruptions intensify due to what NASA calls “the relentless rise” in atmospheric carbon dioxide from increased combustion of fossil fuels.

Maine is ramping up efforts to cut carbon pollution, but global emissions in 2018 reached an all-time high. Atmospheric carbon dioxide levels have now topped 415 ppm, the highest level recorded.

Some warming is already baked into the atmospheric system, scientists warn, and will cause marked upheaval in coming decades – even if rapid cuts are made in carbon emissions. Some climate impacts could descend with hurricane force, while others accrue incrementally.

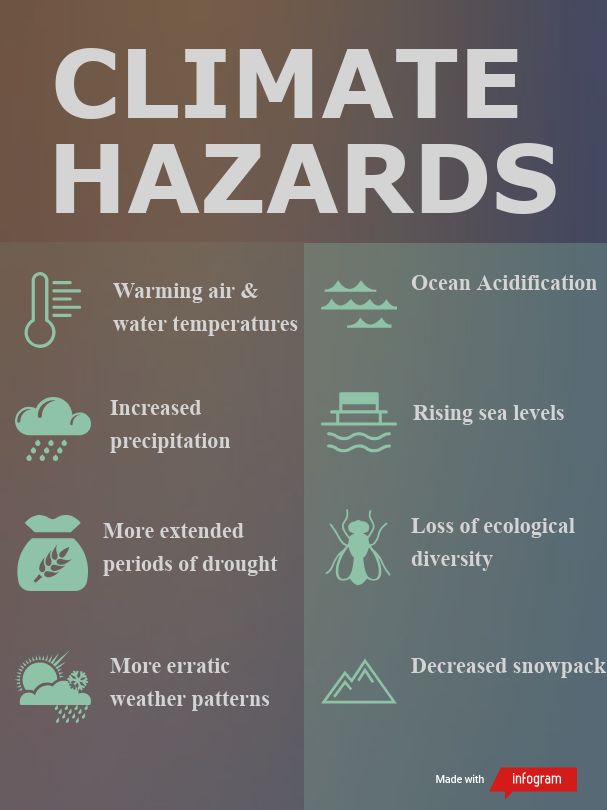

Many of the climate hazards Maine can anticipate are documented in two reports produced by the University of Maine Climate Change Institute. Work is underway on an update of its most recent 2015 report.

Yet these assessments incorporate only minimal economic analysis. Ivan Fernandez, a lead author and University of Maine professor, acknowledges that this “last step, turning it into a dollar sign” is increasingly critical.

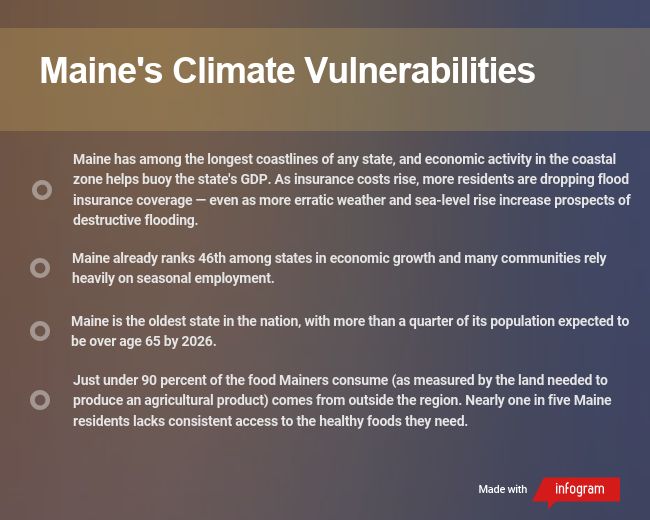

Climate-related stressors threaten to create a perfect storm in Maine, given its existing vulnerabilities: roughly 3,500 miles of tidal shoreline, an aging population, slow economic growth, high healthcare costs, a seasonal economy, crumbling infrastructure, reliance on tax revenues from waterfront properties, and dependence on one primary marine resource.

The Fourth National Climate Assessment (NCA) report, released last fall through the collaborative effort of 13 federal agencies and hundreds of independent scientists, affirmed that the brunt of climate costs will fall on “people who are already vulnerable, including lower-income and other marginalized communities, (those who) have lower capacity to prepare for and cope with extreme weather and climate-related events.”

Much of rural Maine fits that definition. Its small communities have restricted budgets, no redundancy of infrastructure, limited – largely volunteer – emergency response capacity, and aging residents who are ill-equipped to contend with disruptions.

Communities like Stonington are already losing population. Stonington characterizes itself as “one of the older towns in the oldest state,” and expects to lose 40 percent of its residents by 2030, with a third of those remaining likely to be over age 65.

Add to that demographic trend an eastward shift in the lobster fishery and threats from sea-level rise, and Billings says, “Going forward, I could see some real hard times in small coastal towns.”

Setbacks in more densely populated regions could ricochet through the state’s economy. The coastline of York County, for example, is especially vulnerable to sea-level rise and flooding given its geology and development patterns.

A 2008 case study by economists Charles Colgan and Samuel Merrill found that the portions of nine coastal York County towns subject to sea-level rise flooding represented eight percent of total state employment, exceeding the combined employment of 11 of Maine’s 16 counties.

Limited Data

That 2008 study provides a rare look at how climate change might alter Maine’s economic activity.

Most climate research focuses on the physical sciences: “There’s very little funding that goes into economic research, making it extremely difficult to do any studies outside of natural resource extraction and manufacturing,” observes Colgan, a former Maine state economist who now directs research at the Center for the Blue Economy in Monterey, California.

Most climate research focuses on the physical sciences: “There’s very little funding that goes into economic research, making it extremely difficult to do any studies outside of natural resource extraction and manufacturing,” observes Colgan, a former Maine state economist who now directs research at the Center for the Blue Economy in Monterey, California.

Maine’s new Climate Council, which begins work in October, will undertake some economic analyses, says Hannah Pingree, director of the Governor’s Office of Innovation and the Future. “We’re aware that it’s an urgent need.”

Maine is now trying to assess what other states have done, she adds, and has joined numerous regional and national networks like the U.S. Climate Alliance, some of which offer technical support.

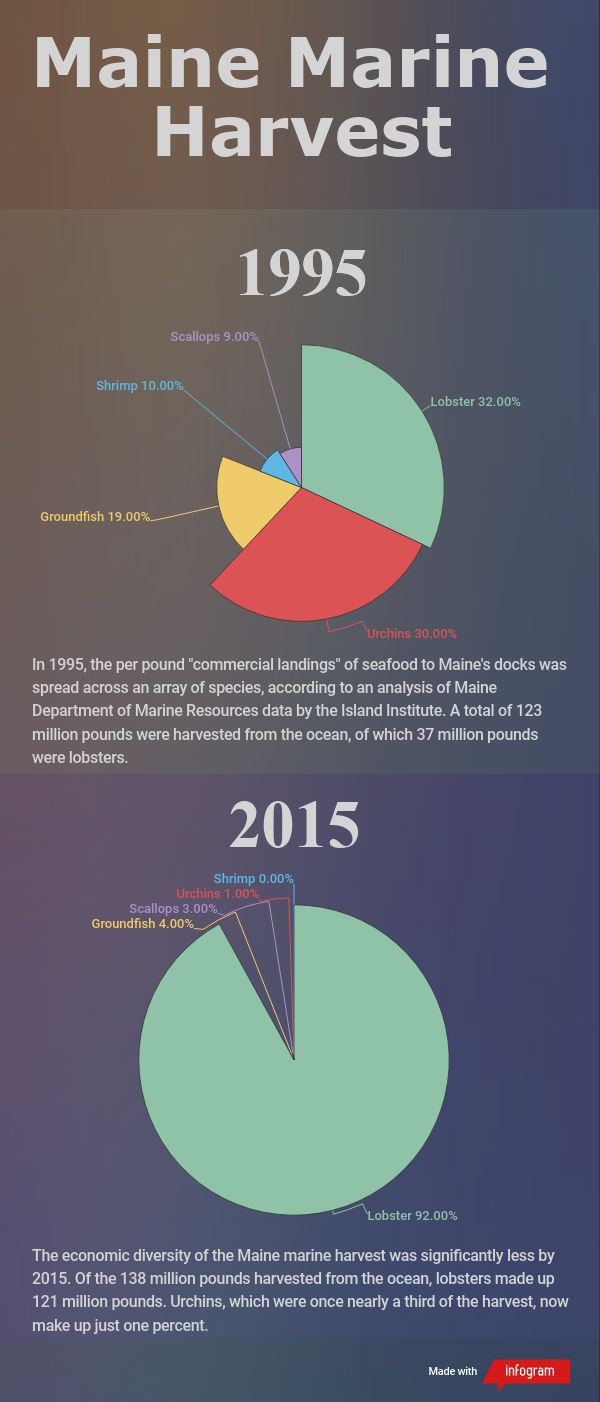

In a socio-economic study of fishery changes in several communities, including Stonington, the Gulf of Maine Research Institute found that Maine’s smaller, rural communities will not fare as well with lobster declines as settings to the south situated closer to urban areas. Many of those ports are already in transition and generating revenues from new species like squid and black sea bass.

The conventional guidance for coping with fishery changes is to shift the species harvested, adapt gear and travel farther, explains Kathy Mills, a Gulf of Maine Research Institute research scientist.

“Those strategies alone won’t get you back to the current landed value [of lobster]” in settings like Stonington, she says, where the “larger geography” works against harvesters vulnerable to “potential shocks… at different points in the system.”

Billings concurs and fears that the combined impact of lost property tax revenues, reduced fisheries activity and increased municipal costs could be “disastrous.”

Vulnerable Sectors

Maine towns dependent on winter tourism, forestry and agriculture share similar vulnerabilities to fishing communities. Winter tourism in the Northeast is likely to undergo a “slow contraction” over coming decades, write economists Jackie Dawson and Daniel Scott, as warmer winters limit the season length for alpine skiing, snowmobiling and ice fishing.

As of 2015-16, winter recreation supported more than 4,500 jobs and added $276 million to Maine’s economy. By mid-century, Dawson and Scott project, only about half of Maine’s 14 alpine ski locations will maintain a season length of at least 100 days (whereas today it ranges upward of 150).

Snowmobiling, being even more dependent on natural snow cover, could drop 70 percent by late-century to around 30 days each year.

Gauging potential losses in forest management and timber harvesting is complicated as costly negatives (such as reduced winter harvesting time or downpours that cause road washouts) might be partially offset by improved growing conditions (due to warmer temperatures and higher rainfall), explains Si Balch, a forestry consultant to Manomet’s Climate Smart Land Network.

Greater unpredictability, he adds, means that foresters and loggers “need to be nimble and adaptable” or risk facing losses in efficiency and profitability.

Among all the potential impacts to forestry, vulnerability to exotic insects and diseases is the “one that keeps me up at night,” reflects Tom Doak, executive director of the nonprofit Maine Woodland Owners.

Once confined to warmer locales, highly destructive insects like the southern pine beetle are marching north. The beetles have reached Cape Cod and threaten to decimate Massachusetts’ 100,000 acres of pitch pine forest. While forest owners generally can expect a slow changeover of species, Doak says, with the prospect of disease or insect infestations, “you’re talking about catastrophic change.”

Farms, too, are at risk from invasive new species and wilder weather patterns, with extreme temperature fluctuations, microbursts, heavy downpours and even tornadoes.

“There’s so much that’s unknown here,” says Tori Jackson, a University of Maine extension educator who chairs the Beginning Farmer Resource Network. She counsels farmers to “be prepared for anything.” There are some “very effective tools – like high tunnels – against some of that variability,” she adds, but they all tend to “increase the cost of getting in.”

Longer periods of drought, for example, can necessitate expensive irrigation systems. Over the four seasons prior to 2019, “blueberry growers experienced drought conditions in mid-season leading up to harvest,” notes Lily Calderwood, University of Maine Extension wild blueberry specialist. “Growers who do not have irrigation have seen yield losses up to 30 percent.”

“Maine does have 14 more frost-free days now than it did in 1930,” Jackson says, but “that’s an average. It’s not a guarantee.”

Shorter winters can increase the risk of a late frost when plants are blooming. In June 2018, a late frost in northeastern Washington County led to losses of 50 to 100 percent on wild blueberry fields, Calderwood reports.

Potential gains from a longer growing season also can be offset, as was true this spring, by increased precipitation that results in planting delays and soil compaction.

Costly Flooding

While weather variability is especially hard for Maine’s farming, forestry, fishing and tourism enterprises, virtually every economic sector is vulnerable to extreme events and what the NCA report calls “cascading failures” in energy, transportation, telecommunications and water/sewer infrastructure.

Storms and flooding are becoming more frequent given that a warmer atmosphere holds more water. The northeastern U.S. saw a 71 percent increase in the amount of rain falling in heavy precipitation events between 1958 and 2012.

Along the coast, flooding risks will be magnified by sea-level rise and storm surge. By mid-century, a one-foot rise in sea level will increase the frequency of annual tidal floods from six events to 46 events. The nonprofit Climate Central research group forecasts that by 2050, homes in York County worth a combined $890 million and those in Cumberland County worth $734 million could be at risk of yearly flooding.

Flooding accelerates erosion, which Stonington’s Teverow sees as one of the most overlooked consequences of climate disruption. There will be “physically less land and less value,” he says, and that devaluation could harm communities, particularly those where erosion threatens critical infrastructure.

Tidal flooding has already begun to devalue shorefront properties, according to a recent study by Columbia University and First Street Foundation, a nonprofit that examines the economic impacts of sea-level rise. Researchers found that between 2005 and 2017, more than 8,000 Maine homes lost value due to increased tidal flooding (through direct impact or the stigma of having nearby roads flood) – potentially removing roughly $70 million in property tax revenues.

Following flood events, property values don’t bounce back quickly, says environmental economist and consultant Rachel Bouvier, adding that it’s especially hard for communities with homes or businesses that repeatedly succumb to floods and require voluntary property buyouts.

Flood events can leave towns in debt, struggling to rebuild infrastructure, adjust to a lower tax base and cover overtime and emergency services. Those factors, in turn, can lower a community’s bond rating, making it harder to replace or upgrade damaged infrastructure.

“Most of rural Maine doesn’t have the resources to handle this on their own,” says Sam Belknap, community development officer at the nonprofit Island Institute. “Additional supports will need to be put in place,” which will likely mean state programs.

“There are no robust federal programs on the front end for prevention,” Belknap adds. Most communities only have access to federal help following disasters, despite a 2017 finding from the National Institute of Building Sciences that every dollar invested by federal agencies to mitigate potential disasters saves society six dollars.

The Island Institute is working in Scarborough, Vinalhaven and Stonington on a study – due out this fall – to quantify what Belknap calls the “economic costs of inaction”– seeing what long-term costs towns could face if they fail to upgrade infrastructure as near-term opportunities arise.

Unprepared

Flooding represents a major financial liability for Maine property owners, given that less than a third of the 31,000 Maine homes in federally designated flood-hazard areas carried federal flood insurance as of 2017. (Few homeowners can afford flood insurance through the private market, and major insurers have begun to drop coverage altogether in some high-risk areas.)

Homeowners are only required to have federally backed insurance if located in the floodplain, notes Frank Kimball, who directs the Maine Bureau of Insurance’s Property and Casualty Division, and they can drop coverage when their property is no longer financed.

Flood maps don’t account for sea-level rise, Kimball adds, so “that doesn’t necessarily make you safe outside” designated zones. FEMA reports that one in four claims now come from properties outside high-risk flood areas.

Assessments of flood vulnerability are still too reliant on historic data, which can create a false sense of security, notes Kerry Emanuel, a meteorological researcher at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. “A big worry,” he says, is that “the risk has already changed a lot, but the statistics being used don’t reflect the current risk much less the future risk.”

Colgan concurs, noting that federal flood insurance maps are primitive and outdated, and towns often resist more accurate maps to sidestep the accompanying insurance mandates. “Even with only minimal sea-level rise (an increasingly unlikely prospect),” he adds, “the whole system is a disaster waiting to happen.”

As flooding incidents proliferate across the country, federal funds may run short, leaving less populous states like Maine with little assistance. Already, Colgan says, federal programs to help with climate preparedness are “woefully inadequate and being defunded all the time.”

As to how the state might respond, Pingree acknowledges that “nobody has a great answer” yet, adding “I don’t know of any state that’s figured out a way to pay for it.”

Colgan hopes to see more “out-of-box” thinking in Augusta about creative approaches, such as the potential for Maine to self-insure through a “catastrophe bond,” what he describes as essentially “a build-your-own insurance company.”

Potholes

The taxpayer tab for climate impacts is apt to rise as floods damage antiquated infrastructure already suffering from inadequate maintenance. Maine’s infrastructure gets low marks from the American Society of Civil Engineers, which issues each state a report card every four years based on current conditions and needs. In its 2017 assessment, Maine received a D+ for transportation, wastewater and dams and a D for roads.

Joyce Taylor, chief engineer at the Maine Department of Transportation, says that MDOT is already planning for “more water to move through” bridges and culverts – sizing new infrastructure for 100-year storms rather than 25-year storms, and scoping bridge projects based on 4 feet of sea-level rise.

A recent study by researchers at Bowdoin College and The Nature Conservancy found that even just 2 additional feet of sea-level rise later this century could leave roughly 10,000 Maine households and businesses with limited access to emergency services during frequent tidal floods.

Taylor says that MDOT is looking more closely at “points of risk” along travel corridors so it can prioritize those as funding permits. But many of those points – like the Deer Isle causeway – pose huge engineering challenges that would involve hefty budgets.

Protecting the Priceless

Because climate change compounds security risks, military personnel call it a “threat multiplier,” a term that could apply equally in the economic sphere. Climate upheaval may simultaneously multiply costs and erode revenues, further straining Maine households and businesses. A recent working paper issued by the National Bureau of Economic Research affirmed an earlier prediction that by 2100 the country as a whole may lose 10 percent of its GDP due to climate stressors.

Those losses could potentially be reduced by investments in preparedness, which research shows pay communities back many times over – with benefit-to-cost ratios as high as 31 to 1. But mobilizing long-range investments can be difficult in a state like Maine, with chronic economic challenges.

Few citizens yet recognize the potential payoff of investing in climate preparedness. A national survey last November found that a small majority of Americans (57 percent) would vote in favor of a $1-per-month fee to combat climate change, but less than 20 percent would support a $100-per-month fee. Even that theoretical amount would be unlikely to meet the mushrooming costs of climate preparedness.

And despite a strong majority of Americans viewing reliance on clean, renewable electricity in positive terms, only about half are willing to pay for it.

Making investments to limit climate impacts and improve quality of life in Maine could provide unexpected paybacks – like reducing the state’s workforce shortages by drawing new residents. The prospect of good, reliable jobs for the future is already changing minds, notes Elizabeth Rogers, communications officer at the nonprofit Coastal Enterprises, Inc. She has “seen people change their tune” to support a community’s energy transition once they realize “this helps reduce costs and provides greater energy independence.”

In his book “Can We Afford the Future?” economist Frank Ackerman writes that “the impacts of climate change are a mixture of things that are expensive and things that are priceless. The ‘priceless’ impacts are often the most important, yet they are difficult or impossible to represent in monetary terms.”

So much of what defines Maine – its cultural traditions, diverse ecosystems, abundant wildlife and passionate, independent people wedded to land and sea – fit into the ‘priceless’ category, eluding traditional economic measures. That makes the task of climate planning and economic forecasting far more complex.

In the Gulf of Maine Research Institute’s initial review of socio-economic impacts in Maine’s fisheries, researchers were humbled by the breadth and depth of work that remains to be done, Mills reports.

Science tends to “isolate single clean questions, yet the climate crisis demands embracing many complexities,” she observes. “We really need to focus on putting more pieces together.”

Resources:

Fourth National Climate Assessment: Northeast

Maine’s Climate Future Report – 2015 update

Confronting Climate Change in the U.S. Northeast: Science, Impacts and Solutions

NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information State Climate Summaries–Maine (2017)

Climate Systems Research Center State Climate Report for Maine

Surging Seas Risk Finder for Maine

Comparison Matrix: Sea Level Rise and Coastal Flood Web Tools