The ethereal refrain of the white-throated sparrow runs through memories of childhood. My own children have rarely heard its call. Bird populations in the U.S. have plummeted since 1970, with 1 in 4 birds disappearing.

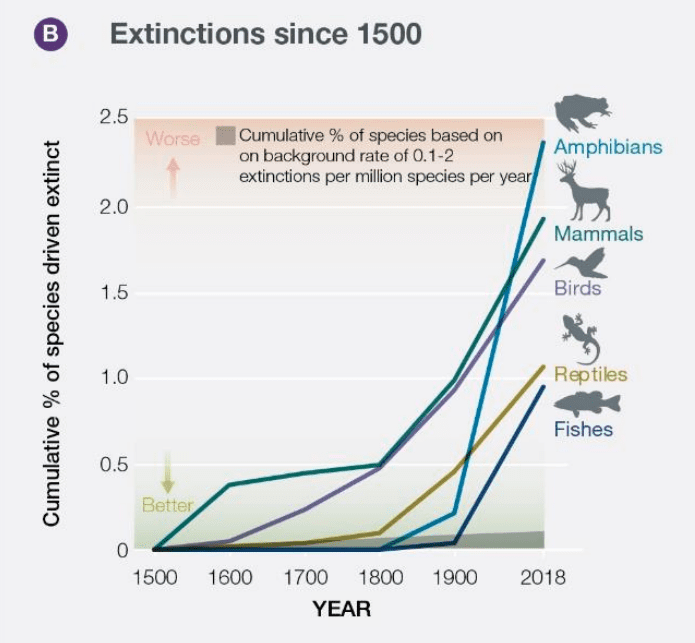

The fraction of global species lost each year is now more than a thousand times the rate that existed before humans, and the United Nations has warned that up to one million species are at risk within decades.

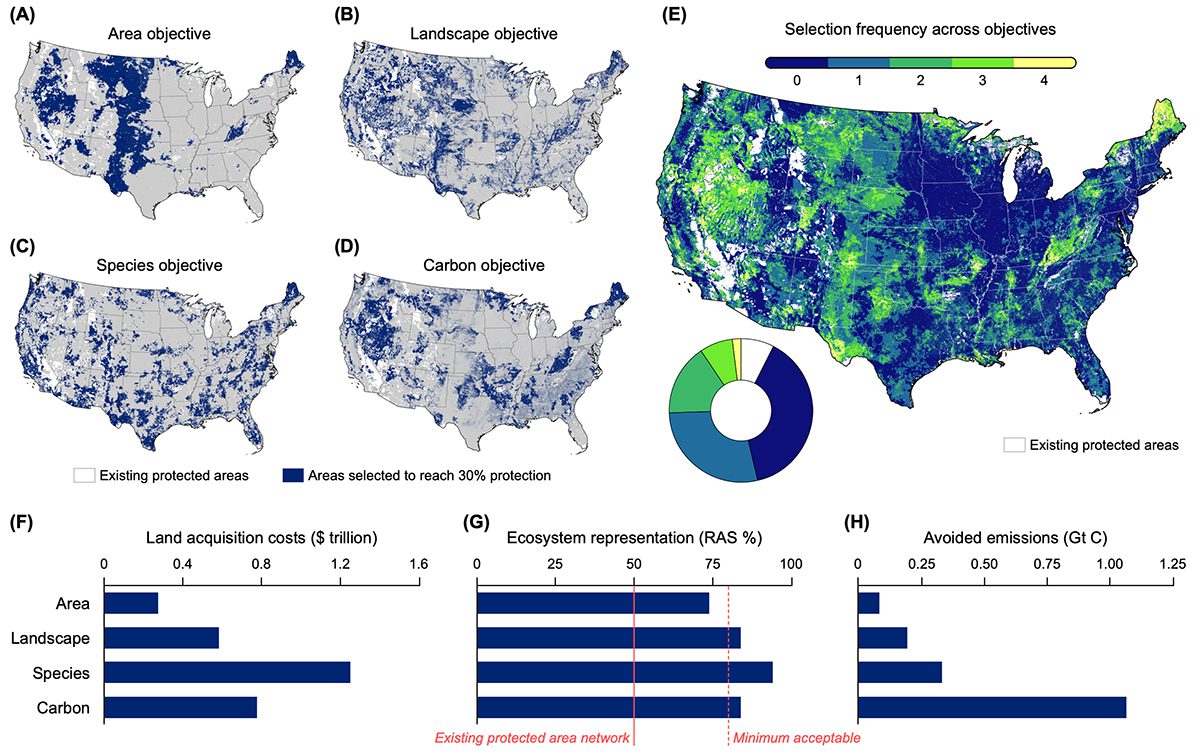

Slowing the pace of extinction and of climate change requires conservation on a new scale. While 30×30 might sound like a construction term, it is just the opposite: a goal to protect 30 percent of lands from development by 2030.

It’s a prescription Earth desperately needs, scientists tell us, given dramatic declines in biological diversity and catastrophic climate tipping points. Nor can the effort end in 2030; the planet needs half its lands conserved by 2050. Protected lands will regenerate ecosystems – supporting wildlife habitat, purifying air and water, locking up atmospheric carbon and helping moderate local weather.

The 30×30 commitment is a vital first step toward keeping our own species off the extinction list.

Acting at every scale

More than 50 leaders have committed their countries to the 30×30 goal, and President Biden recently joined them. Maine is at the forefront of states adopting a similar goal, formalized last December in its Climate Action Plan.

Roughly 21 percent of the state’s land is already protected from conversion to development, according to a geographic information system maintained by the state’s Natural Areas Program. Hitting the 30×30 target will require conserving “roughly another 2 million acres this decade,” said Andy Cutko, director of the Bureau of Parks and Lands at the state Department of Agriculture, Conservation and Forestry.

That acreage represents more than nine times the area of Baxter State Park. What’s envisioned is not park lands so much as a mix primarily of working farms and forests protected through voluntary conservation easements (where private land remains on tax rolls but development is restricted in perpetuity, and a land trust or state agency monitors the property annually).

Deciding priorities to protect Maine lands

Protecting 9 percent more of Maine lands in the next nine years represents a significant challenge, but the state has achieved a similar pace of conservation before. The percentage of protected lands tripled in the two decades following 1990, partly in response to shifting ownership patterns in the forest products industry. Through that transition, conservation helped safeguard the landscapes and traditions that define Maine’s outdoor heritage.

Opportunities for large-scale conservation could still lie ahead, given intergenerational transfers and an increased willingness among some forest landowners to consider conservation easements, said Karin Tilberg, executive director of the nonprofit Forest Society of Maine. “The land trust community works well together. Should opportunities arise, those strong bonds of communication and trust are there,” she added. “The state and nongovernmental organizations are always ready.”

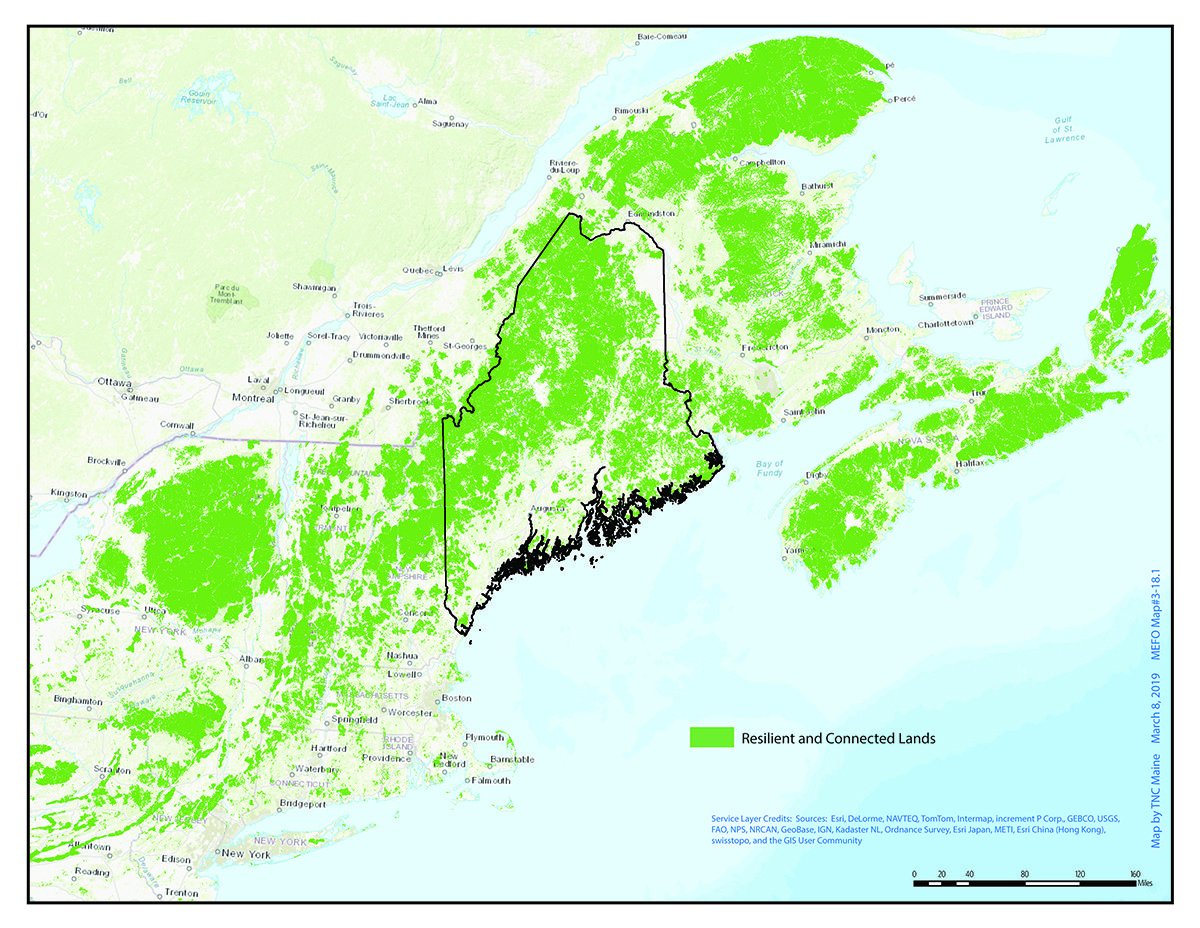

Careful thought has already gone into identifying lands that meet multiple criteria – providing wildlife habitat, sheltering rare and endangered species, offering outdoor recreational opportunities and holding carbon in mature forests. The Nature Conservancy has already developed a resilient land mapping tool identifying areas likely to continue supporting a wide range of species – even if their composition changes in response to global warming.

Working farmland must also be a major part of the lands conserved this decade, given ambitious state targets for increased reliance on local foods. A bill this session, LD 568, would create a Working Farmland Access and Protection Program within DACF to help support further farmland conservation.

Investing in land conservation

On regional and national maps, Maine stands out for its network of ecologically diverse lands, many of them connected so wildlife can move freely across the landscape and plants could gradually shift northward and upslope as the climate warms.

These attributes could help Maine qualify for federal support through programs like the Land and Water Conservation Fund. Thanks to the Great American Outdoors Act passed last fall, LWCF will provide $900 million annually for land conservation. Some of those funds come through the Forest Legacy Program, and Maine projects could fare well competing for those grants, given the high value of its forest lands for carbon sequestration, wildlife habitat and outdoor recreation.

Federal grants typically require a state match, which underscores the critical need to renew funding for the Land for Maine’s Future Program, which has helped protect iconic landscapes for Maine people since 1987. The Legislature is considering two bills for an LMF bond; each would provide a minimum of $10 million in funding a year for at least the next three years.

If voters approve a bond on the November ballot, project funds would likely be available by the summer of 2022, according to the program’s director, Sarah Demers.

The 30×30 target is also helping generate philanthropic interest. It’s “meant to be a big vision,” noted Mark Berry, the forest program director for TNC’s Maine chapter, one that reflects the severity of the climate and biodiversity crises, and can “raise the profile of the importance of conservation.”

Recognizing our interdependence

Despite its name, 30×30 is less about numbers than about fundamentally shifting the prevailing attitude toward the natural world. Unrestrained exploitation and development must give way to ecological understanding.

Honoring our existential interdependence will require what humanitarian Albert Schweitzer termed a “reverence for life.” Indigenous cultures have nurtured this way of being over millennia, but it is largely absent in the dominant culture today. Reclaiming that view will be central to the 30×30 effort. “This step toward sustained coexistence with the rest of life,” the naturalist E.O. Wilson once wrote, “is partly a practical challenge and partly a moral decision.”

Disclosure: The author is a freelance contributing writer for the magazine of the Land Trust Alliance, a nonprofit conservation organization representing 1,000 land trusts nationwide.