The evidence room at the Cumberland County Sheriff’s Office in Portland is bursting with firearms that were confiscated, found or otherwise turned over to the law enforcement agency.

“We have a really strict, really specific way that we deal with all firearms, which is probably at this point, the bane of our existence,” Detective Keith Cook told The Maine Monitor. “They’re very difficult to work with. They’re a problem to store.”

He estimated the office has at least 600 guns that have been there at least two years.

“We’re to the point where we’re pretty much out of space to store firearms right now,” he said.

Maine law enforcement agencies have several options when trying to offload seized or surrendered firearms: sell the guns to a federally licensed firearms dealer, sell them to the public at auction, use them for training or destroy them.

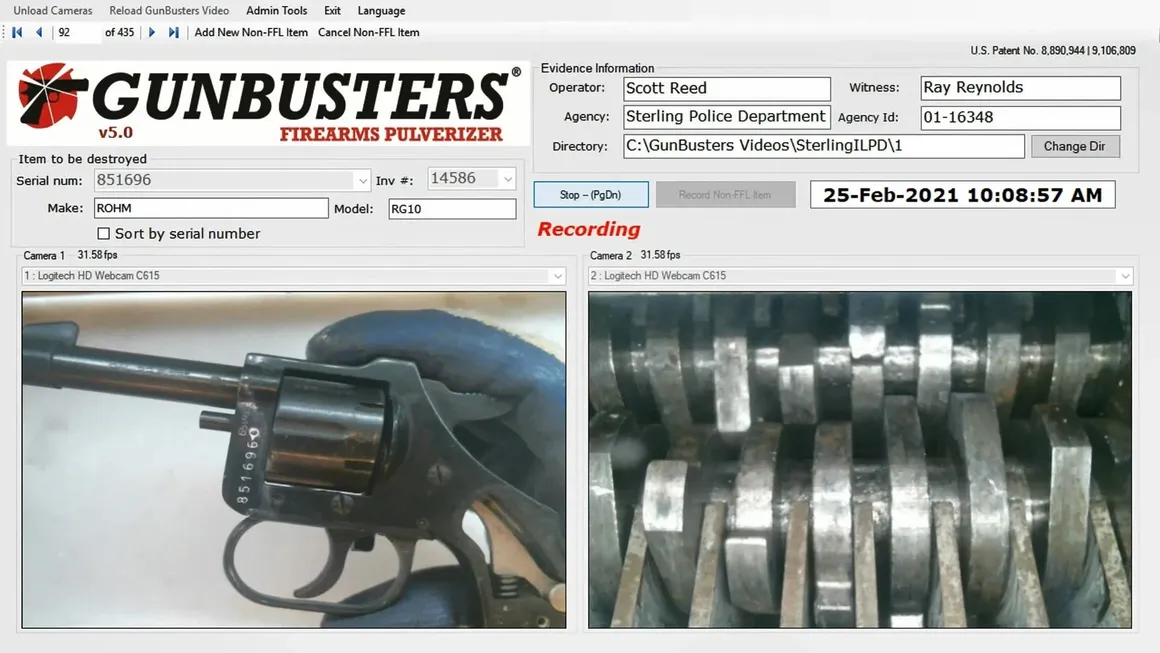

One way the Cumberland County Sheriff’s Office has disposed of guns is by sending them to GunBusters, a Missouri-based company that offers a “safe, simple and secure firearms destruction program free of charge for law enforcement agencies.” The company, whose New England headquarters are in Hermon, claims on its website to have destroyed more than 200,000 firearms for 950 agencies.

“Every firearm that we destroy won’t end up back on the street,” GunBusters of New England’s president, Mack Gwinn III, told a North Carolina business journal last year.

But as a New York Times investigation revealed in December, the guns are not fully destroyed.

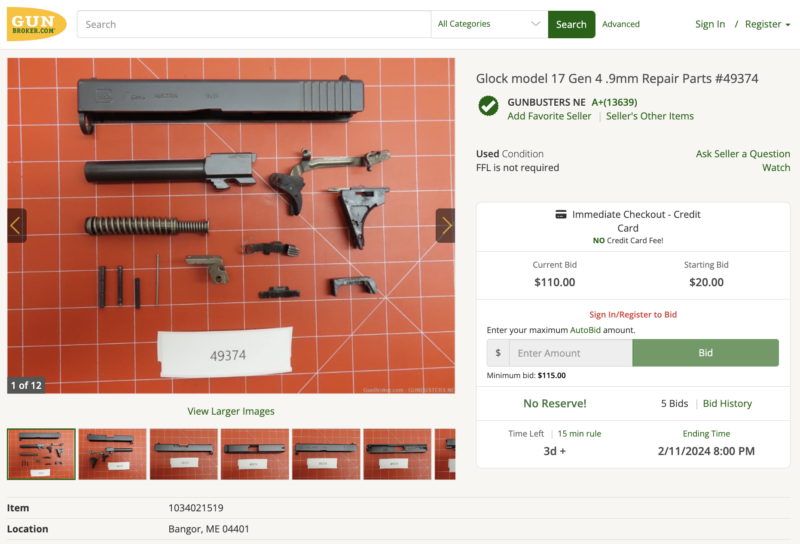

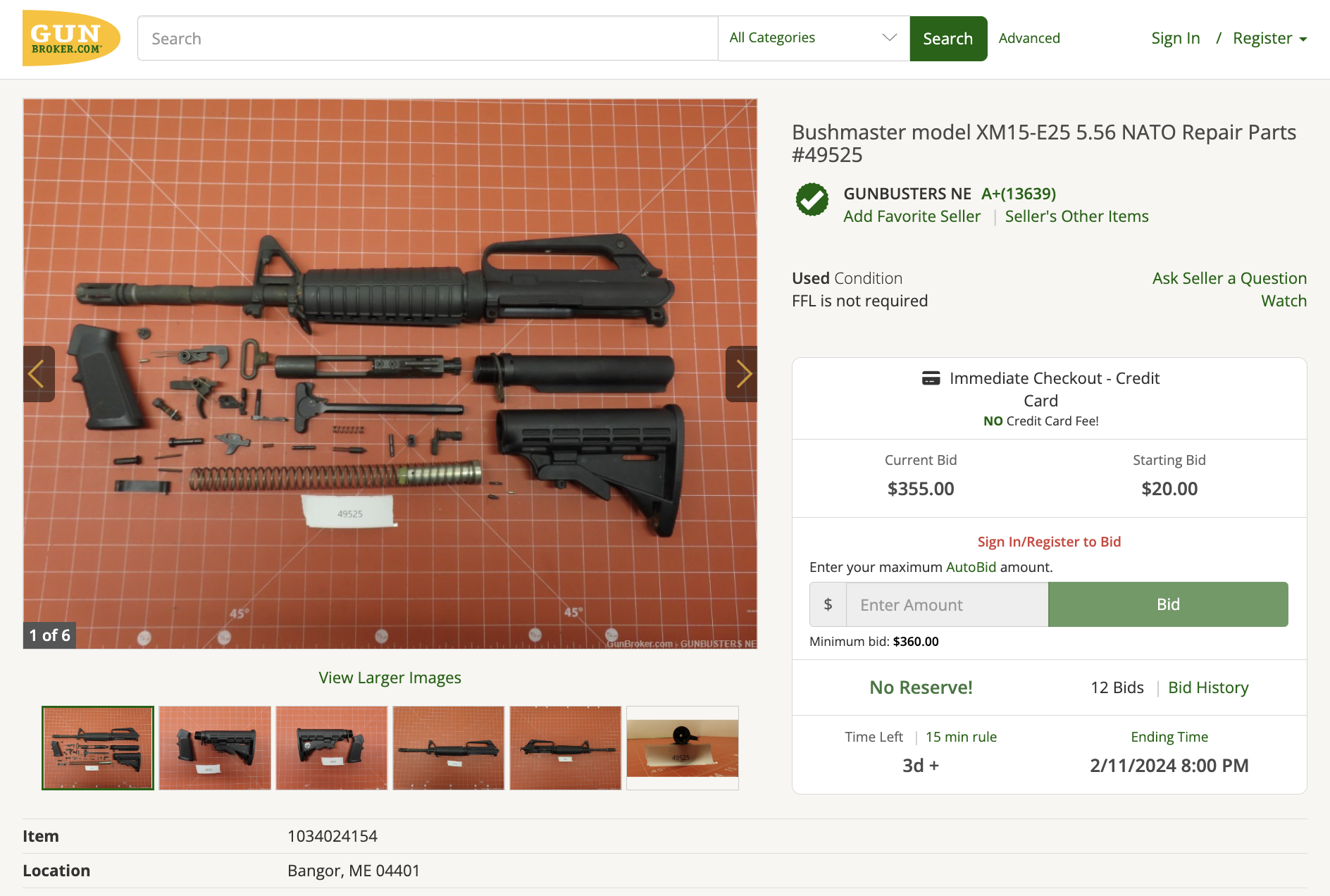

Instead, the company disassembles them, puts the frame or receiver — the only part of the gun that contains a serial number and is regulated by the federal Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives — through its so-called pulverizer, and sells the rest of the components as a gun kit.

Because the kits do not contain the frame (for a handgun) or receiver (for a rifle or shotgun), the main structural element of a gun, they’re not considered complete firearms under federal rules and do not require a background check to purchase.

While a background check is required to buy a frame or receiver, online sellers are able to get around this by packaging unfinished frames with simple templates for converting them into working firearms. These can be easily combined with a gun kit to build an untraceable weapon known as a ghost gun.

As of last week, GunBusters of New England had over 200 gun kits for sale on GunBroker.com, the largest firearms auction website.

These included kits for a Bushmaster XM-15, the same gun model used in the Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting, and other semi-automatic assault rifles similar to the Ruger SFAR AR-10 that was used in the October mass shooting in Lewiston.

They also included at least two models of Glock pistols used by the Portland Police Department.

“The listed parts were removed from a single firearm earmarked for destruction. The frame or receiver was destroyed under court order. We do not sell frames or receivers nor whole firearms, just repair parts,” reads a description under each listing. It notes that no background check is required.

After a Monitor reporter shared the Times investigation with Cook, and he realized the guns Cumberland County had handed over to GunBusters were being sold in parts online, he said he felt his agency had been deceived.

“Our understanding was that the firearms were destroyed. Meaning the whole gun,” he said. “I don’t recall seeing on any of their advertisements, website or other materials, any statements or indication that they sold off parts of the guns we turned over to them.”

Cook said they sent about a dozen firearms to GunBusters the last time they used the company.

A disclaimer on the GunBusters website says the company “will strip the component parts (e.g. grips, magazines, slide assembly, trigger group, etc.) for sale. The sale of the parts and accessories allows GunBusters to offer destruction services free of charge. The ATF-defined receivers/frames are destroyed and video recorded for the department.”

But a Monitor review of the site’s history found that this text was only added in mid-December, following the Times investigation. A previous version of the website stated, “Firearms are processed through the GunBusters Firearms Pulverizer. Each firearm is destroyed individually. Our destruction process exceeds ATF requirements for firearm destruction.”

The GunBusters pulverizer is a large machine with interlocking teeth that crushes the central gun component into small pieces. The process is recorded and a copy of the video is sent to the agency for their records.

According to guidelines published by the ATF, acceptable methods for destroying firearms include melting, shredding, crushing or cutting up the frame or receiver.

The guidelines stipulate that “any method of destruction must render the firearm so that it is not restorable to a firing condition and is otherwise reduced to scrap.”

The Monitor spoke to four Maine law enforcement agencies that have used GunBusters in the past several years, and only one — Portland Police — said it knew the parts were resold as kits.

Kennebunk Police Chief Bob MacKenzie said he was not aware that parts of the guns they sent to GunBusters were being resold.

“In fact, it was my understanding we have video of them destroying the firearms,” MacKenzie said.

GunBusters told the Times that reselling the gun parts as kits is how they can offer this service to law enforcement agencies for free, and agencies could pay for a separate service if they wanted to have guns destroyed in full.

MacKenzie said he planned to ask GunBusters how much that service would cost.

Falmouth Police Chief John Kilbride said his department used GunBusters at least once but not in several years. In 2021, his department partnered with Humanium Metal, a Swedish organization that melts down guns and uses the metal to make jewelry.

Kilbride said he searched for an organization that could destroy the firearms and “turn them into something productive.” He said he relied heavily on the Maine Gun Safety Coalition, whose board he sits on, to vet the organization.

“My experience of almost 30 years in law enforcement has exposed me to a lot of people who are making poor decisions with firearms, and you don’t have a second chance with guns,” said Kilbride, who has been with Falmouth Police since the 1980s.

“It is so traumatizing. I’ve seen families just torn apart right in front of me from a split-second decision, a bad decision, because the accessibility was there,” he said.

In October 2021, Falmouth Police and the Maine Gun Safety Coalition hosted a gun destruction event in the Falmouth Police parking lot, billing it as an opportunity for agencies to clean out their evidence lockers and for the public to drop off old guns. Kilbride said anyone with an unwanted firearm could bring it by, such as a family looking to dispose of a gun after the original owner died or it was used in a suicide.

This marked Humanium Metal’s first partnership in the United States, and profits from the sale of the metal were donated to the Maine Gun Safety Coalition. Humanium Metal offered the service at no cost to Falmouth.

Kilbride said Falmouth Police and other agencies kept a record of every firearm sent to Humanium Metal, as they would for any other firearm that was being destroyed or sold. The guns were cut into pieces and shipped to Sweden, where they were melted down and turned into bangles, pens and other products.

“I think it’s prudent for any police department to promote gun safety and this is just part of that,” Kilbride said.

He’s hoping to host another Humanium Metal destruction event in May.

Firearms come into police possession in a number of ways. Some are confiscated as evidence during an investigation, some are forfeited under a court order, some are surrendered by people who don’t want them, and others are simply found.

“You’d be surprised how many (guns) we recover that are found in the bushes or found in abandoned buildings or an apartment or a house and up in a ceiling tile or something like that,” Portland Police Assistant Chief Robert Martin said. “At least a couple times a month we find one.”

If a found gun is believed to be abandoned, lost or stolen, Maine law says officers must attempt to find the rightful owner and return it, in part by publishing a notice in a newspaper at least 30 days after the gun was found. If no one has claimed the gun within five months, an agency can sell the gun, destroy it or use it for training.

“That’s why my evidence room is full now, because I have guns in there that I tried to get in touch with people, I don’t get calls back or (their) last known number is disconnected,” Cook said of the Cumberland County Sheriff’s Office. “If I don’t get rid of a gun, it just goes right back on the shelf and it sits there until at some point hopefully they call us or we come across them or somehow we can get it back to them.”

Cook said most guns sitting in the evidence room are from court-ordered forfeitures that accompany protection orders. Once those orders expire, the owner has six months to reclaim the firearms. If they aren’t claimed, an agency can sell or destroy them.

Agency officials said firearms often pile up in storage because guns used in a crime must remain in evidence for many years to comply with state laws.

The rules for when and how a law enforcement agency can sell firearms from evidence have received more attention lately: Christopher Wainwright, the Oxford County sheriff, is under investigation for selling firearms that were in evidence to an Auburn firearms dealer.

Last week, county commissioners recommended Gov. Janet Mills remove Wainwright from his position, and Mills appointed a former judge to oversee a hearing process.

Under state law, guns used during a murder or any other unlawful homicide must be destroyed. Agencies can do this themselves, if they have the proper tools, time and manpower, or pay for a service.

Cook said when a family turns over a firearm used in a suicide, he usually brings it to the garage immediately and has the fleet maintenance crew cut it into 15 to 20 pieces so it is “completely destroyed and no way you could ever use it again.” He said he’s destroyed about a half-dozen firearms that way in the past year.

But not all departments have the ability to do this, or the funds to pay for a service, which is why GunBusters is popular.

After reading the Times investigation, Cook said he would be hesitant to use GunBusters, and said his office would probably try to destroy the firearms themselves.

“I’m sure I can speak for Sheriff (Kevin Joyce) when I say when it comes to firearms and how we dispose of them, our biggest concern has been and will continue to be having guns out on the streets that are passed through the Sheriff’s Office hands and then were used in the commission of a new crime,” Cook said. “Which is why we routinely destroy guns ourselves when appropriate.”

Cumberland County no longer sells firearms from evidence, but some agencies do, including Maine State Police.

The state police sell surplus firearms at an annual auction hosted by the Maine Sportsman’s Alliance. MSP hands the firearms to the Department of Administrative and Financial Services, which handles the sale of all surplus property and coordinates with the Sportsman Alliance.

Last year, MSP sold 88 firearms at auction, according to the Department of Public Safety in response to a records request.

Sanford Police also sells firearms as long as they are “fully functioning and not damaged,” Major Matt Gagné said. The department usually works with a local federally licensed firearms dealer, but it’s a rare occurrence because the office normally keeps firearms in evidence for long periods.

“Recently we sold, I think it was like two or three firearms. And that case (they were from) was almost 20 years old,” Gagné said.

When a firearm is damaged and inoperable, the department uses a service to destroy it, though Gagné said that is also rare. The most recent time he could recall, Sanford sent the firearms to Kennebunk, which sent them to GunBusters.

GunBusters of New England did not respond to multiple calls and emails requesting comment.

According to business filings with the Maine Secretary of State, GunBusters of New England was incorporated as an LLC in 2016. Mack Gwinn III is listed as the company’s representative and as president on his LinkedIn page. According to the GunBusters website, he oversees the company’s operations in New England and the Southeast, encompassing Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New York, North Carolina, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Vermont, Virginia and West Virginia.

Gwinn’s father, Mack Gwinn Jr., founded Gwinn Firearms, which later became Bushmaster Firearms. Richard Dyke bought the company out of bankruptcy in the late 1970s, moved its manufacturing facility from Bangor to Windham and turned Bushmaster’s AR-15–style semi-automatic rifle into one of the most popular guns in the country.