Caribou Rehab and Nursing Center last year had more certified nursing assistants turn over than it had CNA positions.

The Aroostook County nursing home typically employs between 60 and 65 nursing aides, administrator Phil Cyr said. Last year those positions turned over 74 times. In a typical year, he might replace 25 or 30 CNAs.

Cyr said one reason for the high turnover is he expects a high level of competence from employees. Sometimes, positions turn over three times before he finds a good fit.

But it’s increasingly difficult to find quality candidates. Cyr offered $20,000 signing bonuses last fall to attract new employees, using recruitment assistance funds from the state. He initially offered $5,000 bonuses but had to keep increasing the amount when his original offer didn’t garner much attention.

Maine nursing homes struggle to fill positions because the work is difficult, low-paid and increasingly dangerous during the COVID-19 pandemic.

This month, MaineCare reimbursement rates increased to allow 225 long-term care facilities across the state to pay their direct care workers 125% of the minimum wage, or $15.94 hourly.

Long-term care officials and administrators called the increase a “welcome first step,” but emphasized that more needs to be done to recruit and retain workers.

Cyr said it’s too early to know how much the rate increase could help his facility. When rates increase, Cyr said it usually takes a couple months to see the “hard numbers” of what it will actually mean for individual facilities.

“It will not hurt,” Cyr said. “How much it helps will only be determined after we see how much they’re talking (about).”

The rate increase, approved by lawmakers last session and signed into law by Gov. Janet Mills, was intended to go into effect in July 2022. But Mills late last month moved up the timeline to address the workforce crisis across the state.

“For the remainder of this fiscal year, the rate increases will prioritize facilities that are below the 125% threshold, with the degree of increase varying depending on current reported wage levels,” said Jackie Farwell, a spokeswoman for the state Department of Health and Human Services. “Starting July 1, 2022, rates will be tailored to each facility based on their labor costs.”

Funding for recent rate adjustments are subject to legislative approval, so there could be a lag before the rates actually change.

“Our direct care workers deserve pay that matches the important work they do for Maine people,” Mills said in a press release at the time. “It is my hope that increasing these rates will allow facilities to increase staff wages in the new year, and help them recruit and retain committed and compassionate workers.”

Mills also said she will propose in her supplemental budget an additional $7.6 million to assist nursing facilities with labor costs through the end of the 2022 fiscal year. And she instructed DHHS to waive penalties on nursing facilities with low occupancy rates.

The wage increase is an important first step but can’t be the only solution, said Angela Westhoff, president and CEO of the Maine Health Care Association, which represents 200 nursing homes and assisted living facilities across the state.

Reimbursement rates historically have not kept pace with rising wage costs, Westhoff said. “That’s a chronic problem.”

Facilities need help retaining current workers with more training opportunities, wage increases and promotions so workers feel they’re growing professionally, Westhoff said. There need to be “multiple points of entry” into the career, including offering more CNA classes to get young people into the workforce.

Pay only part of the picture

It’s also important to consider “wrap-around support” for workers, including child care, affordable housing and transportation. Traditional child care centers close at 5 or 6 p.m., which can make it difficult for parents who work the 11 p.m. to 7 a.m. shift at a nursing home, Westhoff said.

Lack of affordable housing was a major reason Island Nursing Home in Deer Isle hasn’t reopened since closing last fall, the Bangor Daily News reported. At least 26 candidates declined job offers because they couldn’t find housing in the area.

Island Nursing Home was one of the five Maine nursing homes that closed last fall. Many cited staffing as a major reason.

Including the five last year, 18 Maine nursing homes have closed since 2012.

Westhoff said she’s excited about a new state-funded health care recruitment campaign using federal dollars from the American Rescue Plan, which includes $500,000 to promote direct care professions.

Mills previously distributed about $123 million last fall to nursing homes for staff recruitment and retention.

Cyr, with Caribou Rehab and Nursing, said those funds likely would be more helpful than the MaineCare rate increase. His facility received about $1 million from the recruitment and retention funds.

Cyr used the funds to offer large signing bonuses, and reward good behavior and low absenteeism.

Cyr said Maine has done a better job than other states of supporting nursing homes.

“Maine nursing homes are fortunate to have had what they have gotten from the state of Maine,” he said.

Endangered species: Health care staffers

Part of the workforce problem is the pandemic is driving health care workers out of the industry, Cyr said.

“That has driven up wages because there’s not been enough health care workers to go around to satisfy everybody,” he said. “And so we’re kind of stealing from each other with higher wages.”

CNAs — the backbone of nursing homes — still deserve better pay, Cyr said. He starts them at $16 an hour but thinks it should be $20. He can’t do that without higher MaineCare reimbursements.

“If it doesn’t come in, it can’t go out,” he said. “You can’t pay what you never got.”

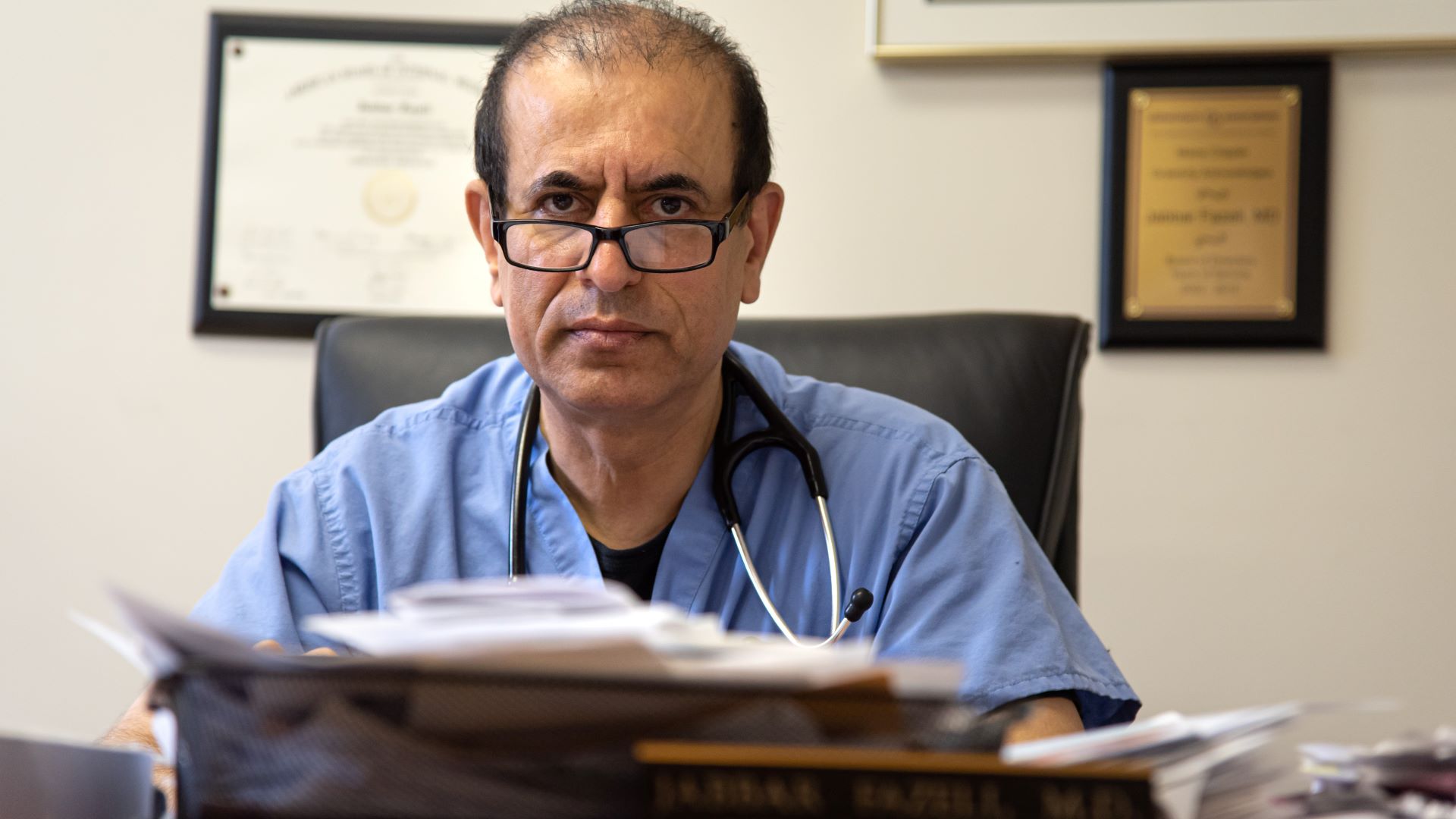

Dr. Jabbar Fazeli, spokesperson for the Maine Medical Directors Association and medical director at two southern Maine nursing homes, said he suspects many facilities already pay direct care workers at least 125% of the state minimum wage. These rates have been increasing during the past two quarters, he said.

The increased reimbursement rate will help “level the playing field” for smaller facilities, he said.

“Operating costs differ from facility to facility, so my guess is this is going to be much more helpful to smaller, more cash-strapped facilities,” Fazeli said. “Maybe rural facilities with less resources, it might make a difference, at least in the short term, for them.”

But with a shrinking pool of workers, facilities increasingly are turning to agency staff, which have much higher rates, because they can’t attract full-time employees with current salaries.

“It’s good that (the rate increase) is evening the playing field and the facilities are able to compete better for the same workers, but in situations where there aren’t enough workers to go around, something’s got to give,” said Fazeli.