Christine Caulfield and her friend had just finished hiking Old Speck Mountain when they stopped at a Fryeburg gas station to get something to eat.

As they left the shop, three middle-aged men confronted the transgender women in the parking lot.

“Take a look, guys,” one of them hollered while walking toward Caulfield and her companion. “This is exactly what’s wrong with our country these days. Maybe we should shoot a few of them and that will take care of it.”

Caulfield eyed their truck with Maine plates and rifles visible in the rear window.

“We don’t want any trouble,” she said, walking slowly to her car.

The 2018 threat was the most menacing Caulfield has encountered, but it is one of the many insults and demeaning incidents the 65-year-old has endured since transitioning from male to female.

“I try not to live in fear,” she said, “but out there in the rural areas, you do pay a lot more attention to your surroundings. You don’t go anywhere alone. You make sure you have your cell phone.”

Caulfield is no stranger to challenges or threats. She is a cancer survivor, served eight years in the Marines, and taught history to middle and high school students for 21 years.

But like many aging transgender people, Caulfield had to navigate a new life fraught with hardships and microaggressions.

Several of her friends abandoned the Yarmouth woman when she transitioned in 2016. Some doctors shunned and belittled her. Congregants from the conservative church she and her family attended scorned her new identity.

“There is an absolute huge amount of negativity that seems to accompany social reactions to somebody who is transgender,” she said. “For someone who is older in life, it takes a while to build up the confidence in yourself. You’ve lived through the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s attitudes (about transgender people) that were so negative they become internalized, and you think, ‘There must be something wrong with me.’

“Yet in reality it’s the other way around. There’s something wrong with a whole lot of other people who can’t just let people be themselves.”

Caulfield knew at age 8 that she was uncomfortable with her masculinity. But those feelings were not easily shared on the Army bases where her dad served in the military.

In the seventh grade, while living on an American base in Germany, Caulfield said she befriended two other youths who also struggled with their gender identity.

“We used to talk about it but had no language for it,” Caulfield said. “There was no Internet to Google anything. The only word we had was transexual.”

When one boy’s parents learned of his desire to be feminine, Caulfield said, they placed him in a psychiatric hospital where doctors performed a partial lobotomy on the child.

“My friend Michael and I were like, ‘I guess this is really bad. There is something really wrong with us.’ ”

Caulfield figured it was safer to bury her feelings.

“It was straight up dangerous to talk about it,” she said.

Thin and underweight, Caulfield believed if she built up her body, she would feel better about being a boy. She lifted weights, played football and ran track. A few months shy of her 21st birthday, she enlisted in the Marines.

“Nobody is going to question your masculinity if you join the Marines,” she said. “But nothing I ever did made the feelings go away.”

Before enlisting, Caulfield met and fell in love with a fellow student at the University of Massachusetts. The dark-haired woman was fiercely independent with a keen sense of humor. The couple married in 1978 and Caulfield thought, “If I have a wonderful life, maybe all these feelings I don’t understand will disappear.”

Caulfield and her wife bought a house in Yarmouth. They had two kids, and Caulfield taught history and social studies in local schools. She coached soccer, softball, track and volleyball.

Despite Caulfield’s busy and fulfilling life, the feelings she kept secret from her wife, colleagues and friends sparked anxiety and nightmares. She sought help from a therapist who surmised, “Maybe you are a transgender.”

Caulfield denied it at first and then thought, “Maybe I am.”

At the time, in 2003, her daughters were 13 and 15.

“We lived in a small town and both my daughters were very involved in high school,” she said. “I just couldn’t come out then.”

Four years later, Caulfield began talking to her family about her lifelong struggle. At age 56, she came out to close friends and a few years later “to the rest of the world.”

While her youngest daughter taught her to do makeup, curl her hair and select stylish clothes, two-thirds of Caulfield’s friends distanced themselves. Some members of her church gave disparaging looks, she said, when she encountered them in the community.

Most of the students and staff at Gorham High were supportive, she added, except for a few teachers who turned away when passing Caulfield in the hall.

“A lot of the microaggressions are nonverbal, but you can tell when you’re being snubbed or subjected to some level of disrespect,” Caulfield said. “Experiencing those kinds of things every single day gets pretty old.”

One summer night, the insults reached a tipping point. She had plans to dine and dance with friends in Ogunquit, a seaside community known for its acceptance of the queer community. Though she had not begun taking hormones to transition her body, Caulfield had started dressing in feminine clothes and using makeup.

As the former Marine captain walked toward the restaurant in a skirt and blouse, she encountered a couple in their 60s.

“Look what’s coming,” the man said to his wife. “I didn’t know Halloween was early in Ogunquit.”

Caulfield approached the stranger and got up close to his face.

“You ought to have more respect for people,” she said. “This town was built on the rainbow. You don’t have the right to say that.”

The man, Caulfield said, was stunned that she confronted him.

“Since that day I’ve taken on more of an activist role,” she added. “I’m not afraid to speak openly.”

CLICK HERE TO SHARE YOUR THOUGHTS ON THIS SERIES

Caulfield is a volunteer for Maine Transgender Network, which advocates for the state’s transgender community. She co-leads an online support group, and offers advice and encouragement for people 35 years and older. Caulfield knows her aging transgender peers risk losing family, friends and colleagues.

“I remind them,” Caulfield said, “that what they are doing takes an awful lot of courage, that they’re willing to lose everything in order to be who they are without reservation or equivocation.”

She also shares stories about the triumphs and tragedies of her own journey. When Caulfield began hormone treatment to transition her body, she was diagnosed with bladder cancer caused, she believes, by the toxic water she and other Marines drank at Camp Lejeune in the early 1980s.

The hormones she had been taking for seven months to induce breast formation, and reduce masculine facial and body hair, had to be terminated. Her doctor worried about how the estrogen may affect her cancer.

Gender-affirming or sex reassignment surgery also had to be canceled, leaving her in a phase Caulfield calls, “Girl Interrupted.”

“Everything just stopped,” she said.

Fortunately, Caulfield added, she was able to have facial surgery to feminize her features. Her prominent male brow ridge was removed. Her angular cheeks became rounder, fuller; her lips were reshaped. Post-surgery, Caulfield looked in the mirror and saw a person she could fully embrace.

“I saw somebody I knew,” she said. “Somebody that was coming out. Someone I really liked.”

This year, Caulfield and her wife will celebrate their 44th wedding anniversary.

“We’re real outliers,” she said. “Most couples don’t stay together.”

In the beginning of her transition, Caulfield’s spouse was uncomfortable seeing her in women’s clothing or accompanying her in public. It took, Caulfield said, a lot of compromise and therapy to figure out their new roles.

“You have to learn to talk openly,” she said, “without feeling shame or getting upset.”

Many spouses, Caulfield explained, worry about how they are perceived as a transgender person’s partner.

“It’s a question of where they fit into this,” Caulfield said. “They worry that other people think they are lesbian or this or that. For the couples that make it through, they understand it doesn’t matter what other people think, ultimately.”

Now, Caulfield said, her wife enjoys going out to dinner or the theater together. Her spouse, she added, is also “pretty protective” of her transgender partner.

“She gets mad if people even look at me sideways,” Caulfield said.

Along with encouraging transgender people through Maine Transgender Network, Caulfield supports a network of LBGTQ people on social media.

Deborah McDonald met Caulfield through other transgender friends on Facebook. Caulfield’s courage has bolstered McDonald along her own journey. Nearly 60, McDonald began taking hormone treatments in March 2020 to feminize her male body. Her wife of 29 years filed for a divorce soon after.

“My wife decided she didn’t want to be married to a woman,” said McDonald. “I still love her and would like to stay together.”

McDonald, who lives in the Sanford area, also lost some longtime friends. Her biggest fear is living alone in the home she shared with her spouse for nearly 30 years.

“When I get depressed about it, (Caulfield) keeps telling me, ‘Hang in there,’ ” McDonald said. “Her support means the world to me.”

Caulfield also encourages her peers to deflect comments or awkward moments with humor. Though she had speech therapy to change her mannerisms and soften her masculine tone, chemotherapy wreaked havoc on her voice. When strangers hear her speak, she often gets odd looks.

“I’m related to Bea Arthur,” she tells them, referring to the deep-voiced actress who starred in the television shows ‘Maude’ and ‘The Golden Girls’.

Still, humor cannot assuage Caulfield’s anger over medical professionals, who she says discriminated against her. One Portland doctor refused to treat her and referred Caulfield to another physician in the practice. A surgeon who operated on her lower digestive tract repeatedly misgendered her, addressing Caulfield as “sir.”

“When the nurses brought it up to him, he said, ‘I don’t care,’ ” Caulfield said. “When somebody like that is doing surgery on you, do you trust them? Is my case less a priority than someone who isn’t transgender?”

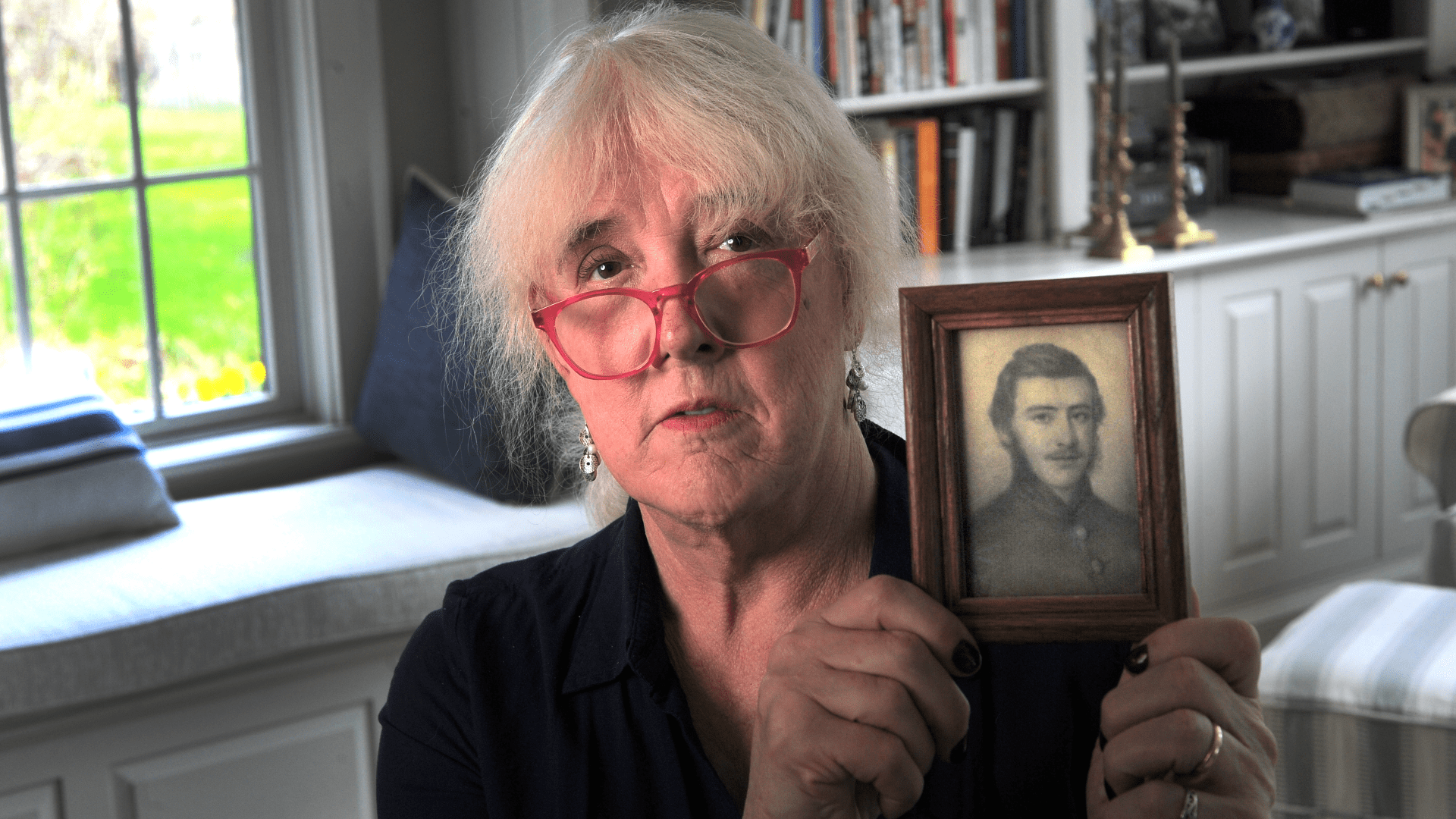

On a brisk April afternoon, Caulfield sat by the window in her family room. Her dog Daisy lay on the floor by her side. Classical music played in the kitchen.

Despite sharing difficult stories, Caulfield’s conversation was punctuated by frequent laughter.

“My wife and daughters say I’m a much better person now,” she said. “I’m happier.”

There are many joys in revealing her true self and being a transgender woman. She can dance with wild abandon, pick out colorful clothes to suit her bohemian style, and take comfort in a queer community that is accepting and nurturing.

“My trans and queer friends are some of the best people I’ve ever met,” she said.

Treatment for bladder cancer forced Caulfield to retire early from teaching high school history, but the self-described historian continues to savor stories of the past. The shelves in her family room are stacked with books chronicling historic people and periods.

Pictures of her daughters and grandchildren are scattered on the shelves. There is also a small pencil drawing of her great-great grandfather, who served in the Civil War. A collector of family heirlooms, Caulfield has preserved his sword, musket, uniform buttons and bible. Her own Marine dress blue uniform hangs in a closet. It is decorated with badges honoring her rank as captain, and her rifle and pistol marksmanship. Photographs of herself taken during her eight years in the corps are tucked away in a box.

Like her father, great-great grandfather and scores of ancestors before them, Caulfield is proud to have served her country. Her family served in the War of 1812, the American Revolution, Korea and Vietnam.

Each of them, she said, sought to protect precious principles. Democracy, freedom and, she adds in a voice barely above a whisper, “equality for all.”

This series was financially supported by The Bingham Program and the Margaret E. Burnham Charitable Trust. We encourage you to share your thoughts on this series by visiting this page. Barbara A. Walsh can be reached at gro.r1763777470otino1763777470menia1763777470meht@1763777470arabr1763777470ab1763777470.