The fingernail-sized chunks of metal in the vial are silvery white, shiny and so soft, says Myles Felch, that they could be cut with a kitchen knife.

It’s a Tuesday morning in early June, and Felch, curator and staff geologist at The Maine Mineral & Gem Museum in Bethel, is demonstrating pieces he plans to include as part of an upcoming exhibit on lithium in Maine, a showcase prompted by news of the discovery of an extraordinary cache of the metal deep in the woods of Newry, 25 minutes north.

Outside it is humid and overcast, but inside the museum is cool, dry and dimly lit, the low light accentuating the spotlights on the crystals in cases lining the walls. For Bethel, a sleepy ski town of 2,500, the presence of such a museum — which one geologist described to me as the “Smithsonian” of rocks — feels unexpected, if pleasantly so.

Perhaps it shouldn’t. The mountains of western Maine, remnants of the chain of Northern Appalachians that formed and then eroded over hundreds of millions of years, are rich in minerals.

The specimens at the mineral museum have names that recall the occult, ones that wouldn’t be out of place in the pages of a Tolkein or Harry Potter novel: bloodstone, schorlite, smoky quartz, morganite beryl, topaz, amblygonite.

Until recently, the most famous deposit in these mountains (“the Big Find”) was discovered in 1972, when gem hunters uncovered more than a ton of the rainbow gemstone tourmaline in a massive pocket near the top of Plumbago Mountain. The cavern yielded some of the world’s finest pink and watermelon specimens of the boron-based crystal, whose color ranges from black to pink to electric blue, depending on the amount of iron, copper or manganese that’s present.

Mary and Gary Freeman were looking for tourmaline when they stumbled on a deposit that may eclipse the Big Find in the history books: a formation of lithium-bearing spodumene crystals potentially valued at $1.5 billion for its use in mobile phones and batteries.

This, of course, is why I was in Bethel in the first place. After nearly two years of reporting on the discovery and its aftermath, including months of legislative hearings on whether the Freemans would ever be able to dig it up, the couple had finally agreed (after much gentle prompting) to bring me to see the deposit, which lies nearly smack in the middle of 7,000 acres of old logging land they own in Newry.

But first I wanted to see the museum, where the Freemans have donated a number of their more impressive crystals over the years, including a spectacular cobalt-colored obelisk of elbaite tourmaline, which sits in a display case devoted entirely to their discoveries.

Mary, wearing a bright pink baseball cap, jeans, hiking shoes and a baguette-cut green-black tourmaline ring (she mined the gemstone herself), met me at the museum, which was closed, just before 10 a.m. on a Tuesday. She led me around to the back door, which Felch held open; the two exchanged pleasantries and a light hug. Gary was out hunting for tourmaline. “He’s finding very dark blue right now but looking for it to lighten up,” Mary offered by way of explanation of her husband’s absence.

We meandered slowly through the exhibits, pulling open drawers full of neatly labeled gemstones. Small white tags named the type of mineral (e.g. Tourmaline s. elbaite), its origin (Dunton Quarry, Newry, Oxford Co.) and the name of the collector (D.M. Sweatt) in black type. Cut gemstones, those that had been shaped by a lapidary (one who polishes or engraves stones) were captioned with their cut and carat.

Felch bounced light-footed through the halls, expounding on supply chains, brine barges and battery technology.

The list of uses for lithium is long and growing: There are batteries, of course, where the metal is prized for being lightweight and able to store a lot of energy, but also mood stabilizers, scientific glassware, computer screens, lubricant (to grease wheel bearings and chassis) and fireworks (to turn flames red). My husband recalled using lithium in the form of spodumene in his pottery during art school, where it lowered the firing temperature, and made glazes more durable and lustrous.

“That might be several different continents right there,” said Felch, unrolling a thin graphite sheet from a battery that will be used as a part of the lithium-in-Maine exhibit, which is scheduled to open later this year. “It’s probably one of the most complicated batteries to produce.”

The lithium on the Freemans’ property is found in pegmatites, a type of coarse granite that was recently adopted by the Maine legislature as the state’s official rock (Felch helped write the bill, an experience he described as strange but rewarding).

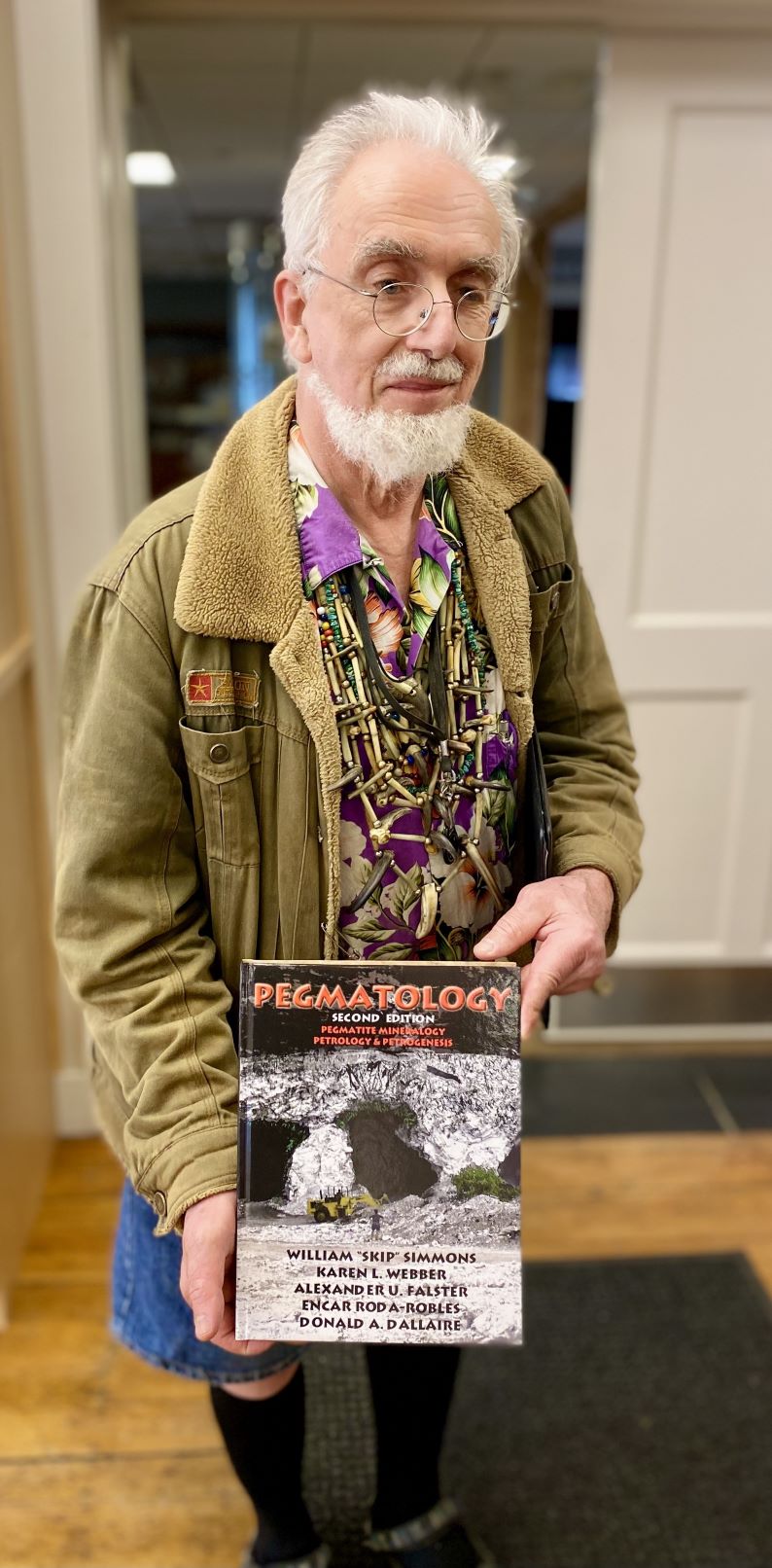

In case I have any questions on pegmatites, we are joined on the tour by a playful, white-bearded mineralogist named Al Falster, who quite literally wrote the book on the subject (“Pegmatology: Pegmatite Mineralogy Petrology & Petrogenesis”).

“They tell me so much,” says Falster, describing the minerals as “highly evolved,” full of incompatible elements that lay out the story of how a rock was formed.

Falster is straight out of central casting, shuffling along behind the group in jean shorts, old Tevas, black knee socks, a purple Hawaiian shirt, a bomber jacket (one button replaced by a safety pin) and a necklace of grizzly bear claws. The necklace, Falster explains, is a gift from the Lakota people of South Dakota’s Badlands, where he lived for a time. It’s the only subject on which he seems reluctant to speak.

When asked about pegmatites, however, Falster pontificates in long, rapid monologues of heavily accented English (he was born in the German state of Bavaria just after World War II), rattling off pages of facts on the rocks, which he has been studying in exotic locales for decades.

To extract lithium from the spodumene in Newry, Falster explains, the process would go something like this: After being mined and removed from the quarry, the crystals would be heated to around 1,700 to 1,800 degrees Fahrenheit, a process that leaves the chemistry of the minerals intact but reorganizes the crystalline structure, turning it into a fine white powder. The powder is then run through a screen to remove unwanted components (quartz, feldspar) and finally soaked in acid, which allows the metal to precipitate out.

There are large hard-rock spodumene mines in Canada and Australia, but much of the world’s lithium comes from brine, the hot, salty water found far below the earth’s surface, which is pumped up and evaporated in a succession of massive open air pools, leaving lithium and other minerals behind.

But extracting lithium from brine is a slow process, one that can take anywhere between 10 and 24 months, meaning production cannot be quickly reduced if demand drops. Brine extraction also consumes massive amounts of freshwater in some of the driest places on earth. At one mining property in the “Lithium Triangle” of South America, home to more than half of the world’s lithium-dense brine deposits, researchers found that flamingos, which rely heavily on wetlands, were having trouble reproducing, and drought-tolerant carob trees were dying at alarming rates.

Hard-rock mining has its own environmental consequences, however, and is hardly carbon-friendly, especially if the large loads of heavy rocks must be trucked long distances for processing. Opening a pit in the earth, even if it will eventually be reclaimed, is devastating to the flora and fauna living there. And processing requires chemicals and produces waste that, if improperly managed, can pollute the land around it.

The group moves slowly through the galleries, stopping to admire particularly eye-catching gemstones. I let out an involuntary, breathy “wow” upon entering the Maine Hall of Gems, where we weave under a pitch-black ceiling among 10 freestanding glass columns, their spotlights trained on intricately faceted stones and dazzling jewels.

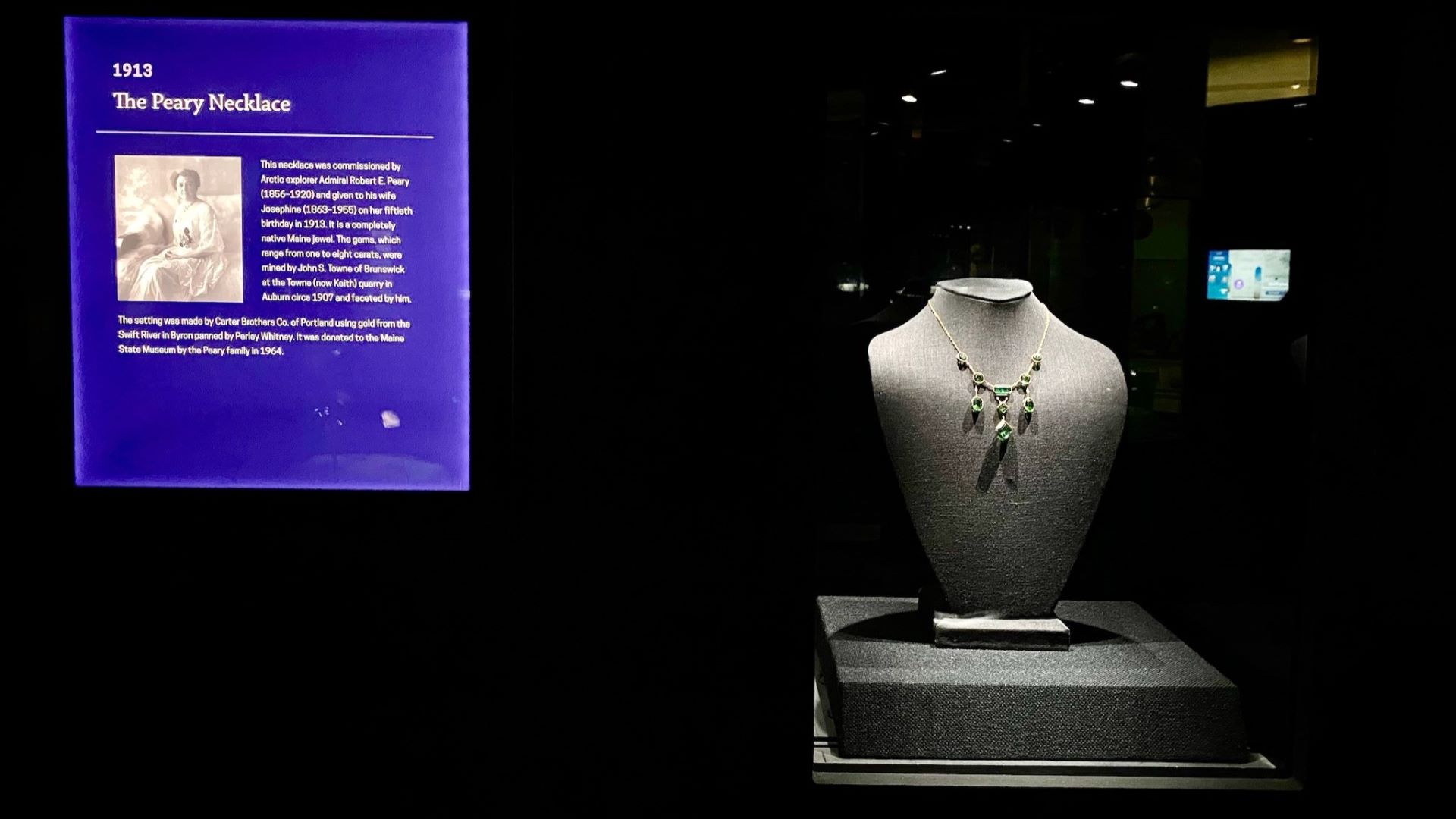

The display includes a necklace commissioned for Josephine Peary, wife of Arctic explorer Admiral Robert E. Peary, made of light green gems quarried in Auburn and set using gold panned from the nearby Swift River.

But the highlight of the tour is two floors below, in a basement research laboratory that is a cinematic caricature of a mad scientist’s lair. An industrial box of Starburst (half full), a canvas sailor cap, flasks, two cans of stuffed grape leaves and a box of unflavored gelatin share counter space with rock samples and sophisticated laboratory equipment worth hundreds of thousands of dollars.

There is not a surface that’s entirely visible; dozens of plugs and silver ventilation tubes dangle from the white waffle ceiling. An Adirondack chair, its back painted with a colorful earth and sky motif, is a repository for an extra Hawaiian shirt, hard hat and crinkled Trader Joe’s bag.

This is where Falster comes alive, flitting from machine to machine, fiddling with microscope lenses and monitors.

“Many people have no idea there’s a lab here,” he says, adding that it’s normally tidier (I’m not sure I believe this).

Falster spends six days a week in this lab, every day except for Sunday, when he’s in the field.

This is where, in 2017, he analyzed a sample from the Freemans’ dig and found the rocks contained more lithium, by weight, than any other known deposit in the world.

The drive to the quarry takes more than an hour, 20 minutes on paved roads that hug the banks of the Androscoggin River, then 45 minutes on a logging road so steep and deeply rutted I’m frequently convinced we won’t make it, even in the couple’s behemoth of a four-wheel drive truck.

As she drives to the base of Plumbago Mountain, Mary and I chat; about the beauty of the region, its late spring greenery and abundant wildlife, the clear water of its dozens of lakes and ponds. The couple has prospected in the area since the 1980s. She doesn’t have a favorite color or type of rock, but remembers her first find, a piece of blue beryl. “It’s the shapes that attract me, the uniformity, the direction of the crystal.”

Raised in Winslow, two hours east of where they now quarry, Mary expresses frustration and bewilderment at the response to the lithium discovery, and the response of the state legislature in particular.

It was hard, she says, to sit through work sessions and hearings where the public, lawmakers and even some educated environmentalists seemed to misunderstand fundamental geological principles, despite efforts by Mary and other geologists to communicate what they knew.

Lawmakers did not take her up on her offer to visit the quarry, which Mary felt would have helped them at least see what they were making rules about. To her, it felt like opposition to mining was, for some, a religion, one that required deliberately disregarding the resources necessary to participate in the intensely mineral consumptive modern world.

“I can educate people but I can’t change their religion,” she said with a little shrug of the shoulders.

We meet Gary, who looks slightly miffed at being pulled away from his gem-hunting (plus, we’re very late). We gather at a wide dirt parking lot and pile into the cab of a truck. It’s cleaner than one might expect for a man who spends his days blasting through rock, although there is, fittingly, a triangular piece of mica, nearly an inch-and-a-half thick, on the floor under the passenger seat.

We take turns, at Mary’s urging, biting flakes of the mineral, which feels gritty beneath the teeth, at odds with its smooth, shimmery plates.

The Freemans made their money designing and manufacturing complex biochemistry instruments for their Florida-based company, Awareness Technology, which also has offices in Austria and the United Arab Emirates. But they rock-hound under the auspices of Coromoto Minerals, which is named for a mine in Venezuela, where Gary dug for gold and diamonds as a teenager while his father worked in the steel industry.

The website of Coromoto Minerals is a throwback to the early 1990s, sporting long uninterrupted chunks of grammatically lax neon green text on a black background. The site mentions lithium and thick spodumene crystals in posts dating to 2004. The last line of the post would prove prescient: “we could be on the cusp on a new and more thrilling phase of this wonderful pegmatite’s story.”

The truck rumbles through a locked gate and weaves among towering piles of sand, gravel and spodumene — the couple has extracted more than 700 tons of crystals under their exploratory permit, and cut a deal with the owner of the sand and gravel quarry at the bottom of the mountain to temporarily store some of it there.

Gary drives confidently up the rutted road. He’s happy to explain the history of the land, which is criss-crossed with logging roads, and the property’s convoluted mineral rights (the Freemans own them). But he sees no point in talking about the likely passage of a new law amending the state’s mining rules, which Mary spent hours preparing for and testifying on.

My visit to the quarry came at a raw time for the Freemans, not long after lawmakers passed a bill out of committee that directs the Maine Department of Environmental Protection to tweak the state’s 2017 mining law (Gov. Janet Mills signed the legislation in early July). The changes will likely allow the couple to remove the lithium in Newry — indeed, that’s the reason lawmakers even entertained the idea of changing the law, which took five years to write.

But Gary could be in his 80s before all the necessary permits are in place and mining begins (he turned 76 in mid-July). The two have already spent more than $700,000 extracting and hand-sorting 700 tons of spodumene from the test pit (they’re allowed to open less than three acres under the state’s rules).

“The idea was we would get enough to show our wares around,” says Gary, somewhat ruefully. Whether they can sell what they’ve already extracted for processing isn’t clear. “We haven’t pushed that envelope yet.”

Despite the legislature’s rules, the Freemans don’t think what they’re doing should be classified as metallic mining at all, pointing out that if they wanted to quarry the spodumene and use it for fill and not for lithium, they would already have been able to get permits under current Maine law.

We step out of the cab into a light drizzle. The forest around us is young, mostly poplar, birch, ash maple and alder. Sumac and raspberries creep through the understory. A few black flies alight; we pass a can of bug spray around and continue the rest of the way on foot. Even on an overcast day the path sparkles, littered with flakes of mica, spodumene and montebrasite.

The pit, when we finally reach it, is underwhelming: just shy of an acre (7/10, to be precise), drilled 200 feet at its deepest.

If there weren’t the odd bits of blasting wire and shock tubes laying around from when the couple dynamited it open, the hole looks like it could have occurred naturally, perhaps as the result of a landslide or small avalanche, at any point in the past few hundred or thousand years. A pool of water at its mouth is filled with tadpoles and bits of spodumene, sparkling at the bottom.

To a layperson, the pit is shimmery but otherwise unremarkable. Myles Felch points out the large crystals that caused such a stir among geologists (many are now broken) and the pockets in which other gems might be uncovered.

Gary, perhaps seeing my mildly dispirited face, tries to put it in perspective — most spodumene crystals elsewhere in the world, he points out, picking up a hefty piece the size of a tennis racket, are roughly as big as a fingernail.

The Freemans pose for photos. I walk in circles around the hole, touching its sharp edges and picking up pieces, trying to distinguish them from the other minerals — quartz, feldspar, montebrasite, mica — littered throughout.

The blackflies begin swarming and the mist that has hung around all day starts to thicken into drizzle. My iPhone is dying, the lithium in the battery dissipating its final charge.

There is a strange irony, I think, that the same chain of Appalachian mountains that gave us the coalfields of West Virginia might now be the source of lithium for batteries designed to fight the climate crisis created, in part, by burning coal from the fields of West Virginia.

We seem destined to be perpetrator and savior, both bound and liberated by our own inventions, generation upon generation left to wrestle with the impacts of the relentless pursuit of progress and convenience.

I turn to go.