The Washington County meteorites were the talk of the state these past few days. Here are some questions and answers about the flash, boom, and awe that started last Saturday.

What was it?

A radar in Houlton determined that the meteorites were overhead at 11:56 a.m. on Saturday, April 8. “Eyewitnesses report a fireball that was bright even in midday, followed by loud sonic booms near Calais, Maine,” a post by the Astromaterials Research & Exploration Science of NASA says.

The falling meteorites were first spotted by the radar at 7,440 meters above sea level. The last observation was 4 minutes, 40 seconds later, at an altitude of 2,376 meters.

The scientists said that the masses that fell were calculated at between 1.59 grams to 322 grams. “Meteorites in this event fell directly into winds of up to ~100 mph, carrying smaller meteorites across the border into Canada,’’ ARES said.

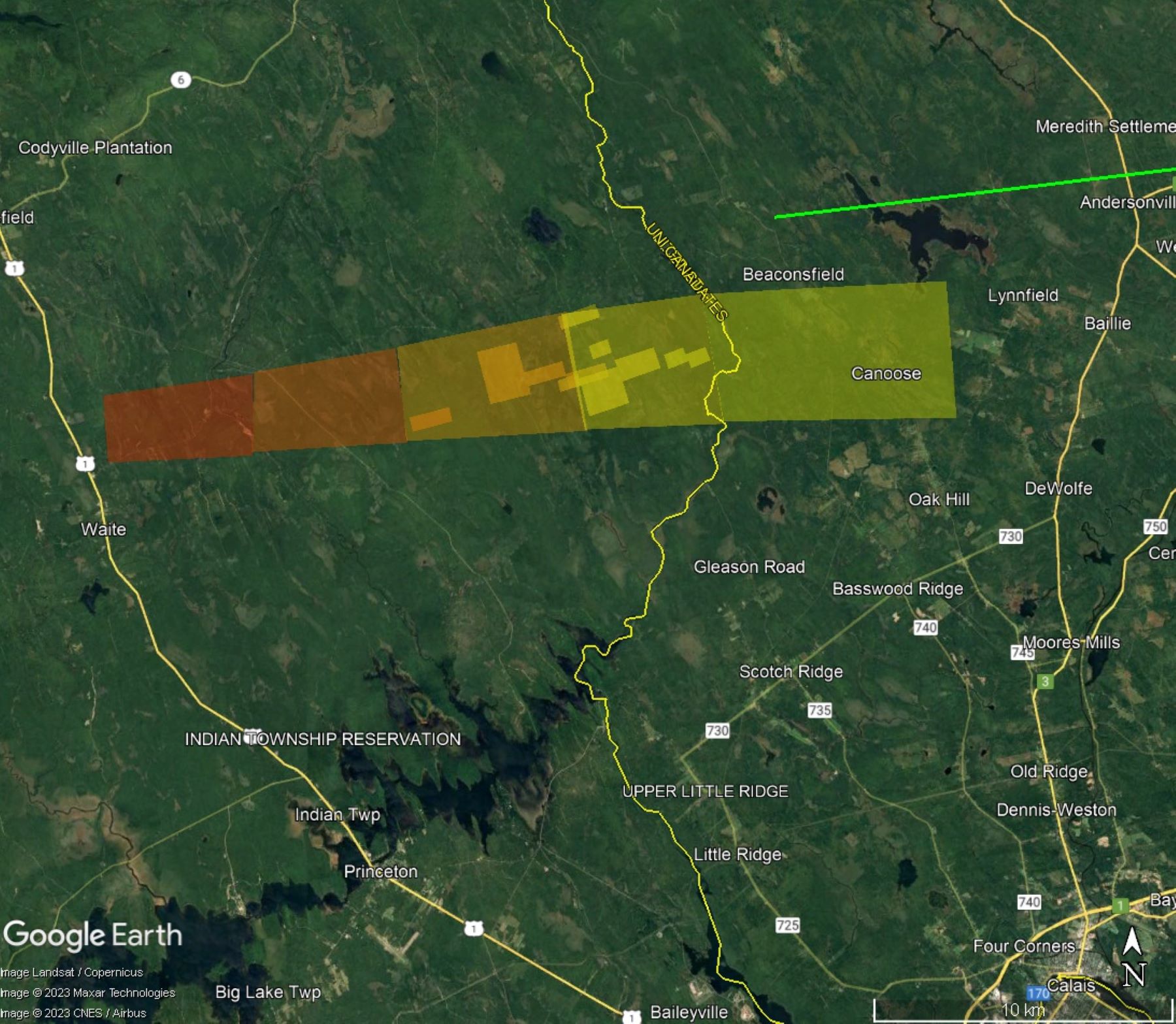

Photos of the presumed debris field place the meteorite fall as roughly northeast of the small Washington County town of Waite to Canoose, New Brunswick.

How were they spotted?

The weather satellite network that tracked the meteorites, called US NEXRAD, was set up in 1996.

“This is the first meteorite fall to occur in Maine since the radars became operational, so it is the first meteorite fall in Maine to appear in weather radar data,” Marc Fries, a planetary scientist with NASA, told The Maine Monitor. “The imagery from these radars is superb for finding meteorite falls because it shows exactly where meteorites landed and the data are immediately released to the public by NOAA.”

How common are meteorites in Maine?

In all, five meteorites have been retrieved in Maine between 1898 and 1978, though this is the first one tracked by weather radar.

“There are undoubtedly more meteorites in the Maine wilderness but forests are notoriously difficult terrain for finding them. Forests eat meteorites,” Fries said by email.

The Portland Press Herald reported this context:

“The American Meteor Society tracks fireballs worldwide and last year recorded reports of 500 fireball events in the United States alone. But recovering meteorites after a witnessed fireball is much rarer, and only happens about seven to 10 times each year worldwide. Last year, five meteorites were recovered following a witnessed fireball.”

What is the difference between a meteorite and a meteor?

The word of the week was “fireball.” But NASA offers a glossary that can help us distinguish between asteroids, meteors, and meteorites. The NASA definitions:

Meteoroids are objects in space that range in size from dust grains to small asteroids. Think of them as “space rocks.”

When meteoroids enter Earth’s atmosphere (or that of another planet, like Mars) at high speed and burn up, the fireballs or “shooting stars” are called meteors.

When a meteoroid survives a trip through the atmosphere and hits the ground, it’s called a meteorite.

What should you do if you find one?

“If someone finds one, they have the option of keeping it for themselves or they can donate or sell it to a collector, a museum, or a research institution like the Smithsonian. (They can also divide it up and sell, donate, and/or keep pieces as they choose.)” Fries said.

Fries said that NASA doesn’t collect meteorites, but he is happy to look at pictures to help determine if it is an actual meteorite.

“Before any of this happens, however, for any meteorites found on private property, in the US meteorites belong to whomever owns the property on which they are found. Meteorites that fall on public property such as roads historically belong to the finder. Any search performed on private property should only happen with the permission of the landowner,’’ he said.

How can you tell if it is a meteorite?

The University of Alberta offers this advice:

Check if the specimen feels unusually heavy for its size. Many meteorites (typically iron meteorites) are quite dense and feel heavier than most Earth rocks.

Test the specimen’s magnetism using a standard fridge magnet. Nearly all meteorites contain iron-nickel metal and attract magnets easily.

Check for holes or bubbles in the specimen. A true meteorite will not have any holes or bubbles at all. If your specimen does, it’s likely slag or some other stony matter.

Examine the outer-layer of the specimen for a thin, black, eggshell-like crust. When a meteor falls through Earth’s atmosphere, the outer surface of the rock melts, forming what’s known as a fusion crust.

If your rock passes all these tests, the university says, you might have yourself a meteorite.

Want to know more? Go to the University of Alberta’s YouTube video on identifying meteorites.

What’s that about a reward?

Darryl Pitt, chair of the meteorite division at the Maine Mineral and Gem Museum in Bethel, told the Associated Press that the museum wants to add to its collection of moon and Mars rocks, Pitt said, so the first meteorite hunters to deliver a 1-kilogram (2.2-pound) specimen will claim the $25,000 prize.

“With more people having an awareness, the more people will look — and the greater the likelihood of a recovery,” Pitt told the AP Wednesday.

In a Facebook post, the museum said it is able to test specimens for identification, but appointments must be made first. “Results from testing will be available in 5 to 10 business days and there is a cost due to specimen preparation that is needed for testing.”

According to the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, the Washington County meteorite fall drew Roberto Vargas of Hartford, Conn. to the Maine-New Brunswick area on Monday. He didn’t find anything, but planned to return this weekend.

If he finds something, it would be his fourth meteorite in the past year.

“There’s nothing like that feeling of being the first person to touch a 4.6-billion-year-old rock that was in space, you know, a week ago,” Vargas told the CBC.

Sign up here to receive The Maine Monitor’s free newsletter, Downeast Monitor, that focuses on Washington County news.