Editor’s Note: The following story first appeared on May 13 in The Maine Monitor’s free environmental newsletter, Climate Monitor, that is delivered to inboxes for free every Friday morning. Sign up for the free newsletter to get more important environmental news from reporter Kate Cough by registering here.

Unless you’ve been living North Pond Hermit-style (actually, he kept up on the news), you’ve heard by now of the New England Clean Energy Connect, aka Central Maine Power’s Corridor project. You may even have voted on a referendum related to it last fall.

And you are probably hearing a lot about it again this week, because there are two cases before the Maine Supreme Court, as well as a hearing at the State Board of Environmental Protection, that will determine whether the plan is allowed to move forward.

A lot of you have been following this extremely closely and will likely notice things that I’ve omitted. I apologize in advance. I’m going to focus on what led us to the court cases, rather than the arguments on both sides, which you’ve likely heard at this point.

The courts, as courts tend to do, will be deciding on a very narrow set of questions, but the answers could have far-reaching implications for permitting and approval of high-impact transmission lines going forward.

They could even set a precedent in which voters can block large infrastructure projects after they’ve been permitted, as Robin Millican, director of policy at Breakthrough Energy, a group that is promoting various efforts to reduce emissions but is not involved in the project, told the New York Times last week.

This (very brief) guide is intended for those who, like me, have sort of forgotten how we even got here. Most of the links below go to primary source documents (court filings, permits, etc.) if you have a few years and are interested in reading them for yourself.

A few of the players and some fun facts:

Central Maine Power: 123-year old utility company serving 600,000 electric customers in central and southern Maine. CMP generated and distributed power in the state until the year 2000, when the Maine Legislature forced companies to sell off their generating assets (like power plants, hydroelectric facilities and other energy-producing entities) and split them from the transmission and distribution system (the part that delivers that power to homes, like poles and wires).

Like other energy companies in the state, CMP has been acquired numerous times over the years in transactions approved by the Maine Public Utilities Commission. It was first sold to an out-of-state owner, New York State Gas & Electric, in 2000.

Avangrid: The parent company of Central Maine Power and a subsidiary of Iberdrola Group, which is an international energy conglomerate headquartered in Spain. Avangrid owns and operates eight electric and natural gas utilities throughout the northeast.

Hydro-Québec: A company owned by the government of Québec, which is its sole shareholder. Hydro-Québec was established by the government in 1944 from private firms. The company has 63 generating stations, 62 of which are hydroelectric.

Hydro-Québec provides about 95% of the province’s electricity and also exports power to New York, Vermont and Massachusetts, as well as a number of other Canadian provinces. It produces about 40 terawatt hours of excess energy each year, which are stored in reservoirs.

That’s a lot. The average Maine household uses 6,840 kilowatt hours per year. One terawatt hour = 1 billion kilowatt hours, so one terawatt hour could provide energy for around 5.8 million Maine homes, or about ten times our current number of households.

ISO New England: A nonprofit created in 1997 that oversees the New England grid. The organization was formed from the New England Power Pool, which was created because states wanted a backup plan after the Northeast Blackout of 1965 shut down power for millions across the region.

Maine’s energy use is low in comparison with many other states, but it still does not generate enough energy to meet demand, which is where the regional grid comes in. The grid is also used to minimize interruptions when there are problems.

A tale of two court cases

2014: The Maine Bureau of Parks and Lands issues a lease allowing CMP to cross two public lots in the upper Kennebec Valley. This is for a transmission line unrelated to the corridor project but will become important later. The right-of-way was granted 58 years ago by the State Forest Commissioner.

2016: Massachusetts Governor Charlie Baker signs a law requiring his state to seek long-term contracts for offshore wind farms and land-based renewable energy. The law calls for 9.45 terawatt hours of “clean energy generation,” which could be a combination of solar or wind with a hydropower backup (because solar and wind generate power intermittently, they must be supported for grid purposes by energy storage or a more consistent generating plant).

The law means that Massachusetts will likely have to acquire around 1,200 megawatts of hydropower or between 1,700 to 3,000 megawatts of onshore wind and hydropower. Hydropower has a higher capacity factor — how much energy a facility actually generates compared to what it could theoretically provide — than wind or solar, which is why fewer megawatts of hydropower would be necessary to meet the demand, and why it’s an attractive option for Massachusetts’ officials.

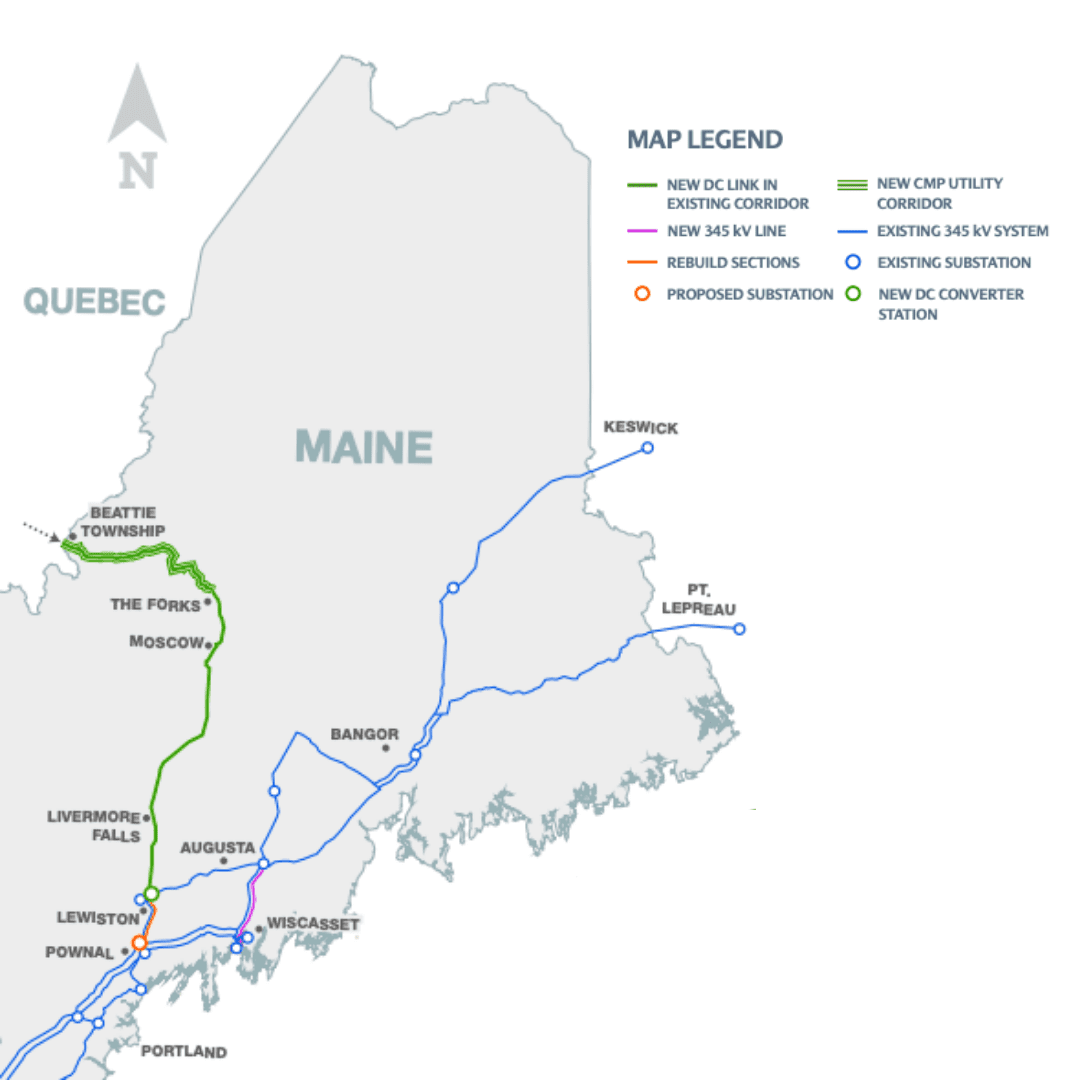

2017: CMP announces plans to build the transmission line and begins applying for permits, including from the Department of Energy, the Army Corps of Engineers, the Maine Public Utilities Commission, the Maine Department of Environmental Protection, and the City of Lewiston, where the new line would connect to the existing network.

As part of the project, CMP also plans to build a $200 million station in Lewiston to convert direct current (which travels more efficiently over transmission lines) from Canada to alternating current (what we use in our homes and businesses). The company plans to start construction in 2019 and be finished by 2022. The $1 billion proposal, called New England Clean Energy Connect, would be paid for by Massachusetts’ ratepayers and provide up to 1,200 megawatts of energy.

The project calls for 145 miles of new transmission lines, most of which (92 miles) would be strung along existing poles. The rest (53 miles) would be new corridor. The company’s right-of-way would extend for a width of 300 feet beneath the lines, 150 feet of which would be cleared of vegetation to install 850 new poles.

2018: CMP wins the bid to build the project after a plan in New Hampshire falls through.

2019: The Maine Public Utilities Commission grants a key permit for the project called a Certificate of Public Convenience and Necessity. This permit is required to build almost any transmission line in Maine, and means the Commission has determined that ratepayers will benefit from a proposal.

2020:

May 11: The Maine Department of Environmental Protection approves the project.

June 10: The Natural Resources Council of Maine appeals the Department of Environmental Protection’s approval, arguing that “there will be significant adverse environmental effects if CMP begins construction.”

June 23: The Bureau of Parks and Lands amends and restates that lease agreement we talked about earlier. The renegotiated lease increases payments from less than $5,000 up to $65,000.

June 26: Sen. Russell Black (R-Franklin) and a number of other plaintiffs, including the Natural Resources Council of Maine and Rep. Seth Berry (D-Bowdoinham), sue CMP and the Bureau of Public Lands over the lease agreement. The plaintiffs argue that the project represents a “substantial alteration” to the lease area, which would require a two-thirds approval by the state legislature.

October 27: Three environmental groups, the Sierra Club, the Natural Resources Council of Maine and the Appalachian Mountain Club, file a lawsuit against the Army Corps of Engineers. The lawsuit challenges the Corps’ finding of “no significant impact” in its Environmental Assessment and argues that by conducting an Environmental Assessment, rather than an Environmental Impact Statement, the agency “failed to take the required ‘hard look’ at the CMP Project’s adverse environmental impacts” and failed to comply with the regulations of the National Environmental Policy Act.

November 4: CMP receives a permit from the Army Corps of Engineers.

2021:

January 15: The project receives a permit from the Department of Energy, allowing it to begin construction.

August 10: Remember that lease agreement? A judge at the Kennebec County Superior Court reverses the decision of the Director of the Bureau of Parks and Lands’ to enter into it, finding that the Director had “exceeded his authority.”

August 12: The Maine Department of Environmental Protection initiates proceedings to suspend the approval of the permit it issued because the agency says that the company “will not have a lease to construct the approximately 0.9 mile portion of the transmission line approved in this location,” which is “necessary to the overall project purpose of delivering electricity from Quebec to the New England grid.”

August 13: Central Maine Power, NECEC Transmission, LLC, and the Bureau appeal the court’s decision in the lease agreement case.

November 2: After the most expensive referendum campaign in state history, with $100 million spent on both sides, voters approve a ballot initiative retroactively banning the construction of “high-impact” electric transmission lines in the Upper Kennebec Region, including the NECEC, going back to 2014. The referendum also requires a two-thirds vote of each state legislative chamber to approve high-impact electric transmission line projects using public land retroactively to 2020.

November 3: CMP’s parent company, Avangrid, files a motion asking the Maine Business and Consumer Court to block enactment of the ballot initiative.

November 23: The Maine Department of Environmental Protection suspends the permit it issued for the project “as a result of the approval of the Referendum.”

December 16: A judge at the Maine Business and Consumer Court denies the motion by Avangrid for an injunction that would delay implementation of the ballot initiative.

2022:

May 10: The Maine Supreme Court heard oral arguments in two cases: NECEC Transmission LLC et al. v. Bureau of Parks and Lands et al. (the referendum case) and Russell Black et al. v. Bureau of Parks and Lands et al. (the lease agreement case).

May 17 & 18: To make everything even more confusing, the Maine Board Environmental Protection is slated to take up the Natural Resources Council of Maine’s appeal of the permit at its May 17 & 18 meeting.

The cases, as the Portland Press Herald noted have drawn national attention, in part because “New transmission lines will be crucial for states in the Northeast that have aggressive climate change goals because they hinge on phasing out oil- and gas-fired power plants and electrifying their economies with renewable sources.”

But it’s not going to be easy. A planned 339-mile underground line from Hydro-Québec to New York has also divided environmental groups in that state.

“At the end of the day, everyone might want more transmission for renewable energy,” said Timothy Fox, vice president at ClearView Energy Partners, an independent research firm, told the New York Times. “But no one wants it in their backyard.”

To read the full edition of this newsletter, see Climate Monitor: All CMP Corridor, all the time.

Kate Cough covers climate change and the environment for The Maine Monitor. Reach her by email with ideas for other stories at gro.r1769636586otino1769636586menia1769636586meht@1769636586etak1769636586.