The ongoing impacts of the pandemic on Washington County’s demographics, economic health and housing crisis were spotlighted during a virtual presentation on March 22 from Charles Rudelitch, executive director of the Sunrise County Economic Council.

Along with the acute changes happening in the county, Rudelitch incorporated a broader lens to put the pandemic into perspective and look at potential long-term ramifications of such factors as population shifts.

Before presenting his findings, Rudelitch qualified that the data set was far from conclusive at this point, noting in particular that as the census occurred in early 2020 it did not capture any of the population changes, meaning other sources were consulted. Other categories of consideration have more robust data available but were still somewhat out of date.

“In most cases we only have information from 2021, or in a few cases, from early 2022,” Rudelitch said. “And we don’t know how these trends are going to play out in the economy.”

Population changes remain murky

Historically speaking, “Washington County is a place where the population has been declining, in general, for about the last 120 to 130 years,” Rudelitch said. The only exception, he noted, was during the 1970s when the area experienced a “back to the land boom” fueled in part by artists and others moving out of New York in search of lower rent and a simpler life.

While the current population expansion may be similar, it’s too early to tell. “We’re not sure what’s happening now,” Rudelitch said.

Data from the 2020 census show the population of the county at 31,095, or nearly 2,000 people less than the 2010 census recorded. Preliminary data from the U.S. Census Bureau project a population of 31,437 through July 2022, showing a modest increase through that time period. It’s far from the whole story.

Residents of many communities in Washington County have seen an increase in newcomers from across the country, some of whom have opened businesses or otherwise joined the workforce. Without current census data, however, “we don’t know how many people moved here,” Rudelitch said, and without a crystal ball, “we don’t know how many will be staying.” Additionally, the current available data do not reflect how many residents — new or old — “moved out quietly” in the past few years.

Aside from the changes to the population’s size, Rudelitch also noted the importance of considering the age of the population. Washington County is one of the oldest counties in one of the oldest states, and that will make an impact on population going forward. “The overall population is declining,” Rudelitch said, “and we do not have replacement cohorts.”

As a result, there are communities in Washington County that are getting smaller and smaller, “some of which may become so small that they can no longer maintain the functions needed for the town,” Rudelitch said.

RELATED: Can a town just dissolve? Dennysville considers de-organizing.

If the birth rate increases, however, or if enough people move in from other places, the situation could change and the population could stabilize or increase.

“We don’t really have an option of a steady state,” Rudelitch said. “Our communities are going to change one way or the other.”

Labor force challenges

The county’s population and the age of that population are directly tied in with its available civilian labor force. With the overall age of the population increasing, the labor force is declining gradually. The civilian labor force in the county has decreased from 14,035 in January 2009 to 12,707 in January 2023.

Washington County struggles with a lower workforce participation rate than most of the state. The county’s labor force participation rate is 52.5%, per the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the second lowest of the state’s 16 counties.

Maine itself is at 62.9%, trending behind the rest of New England by a few points.

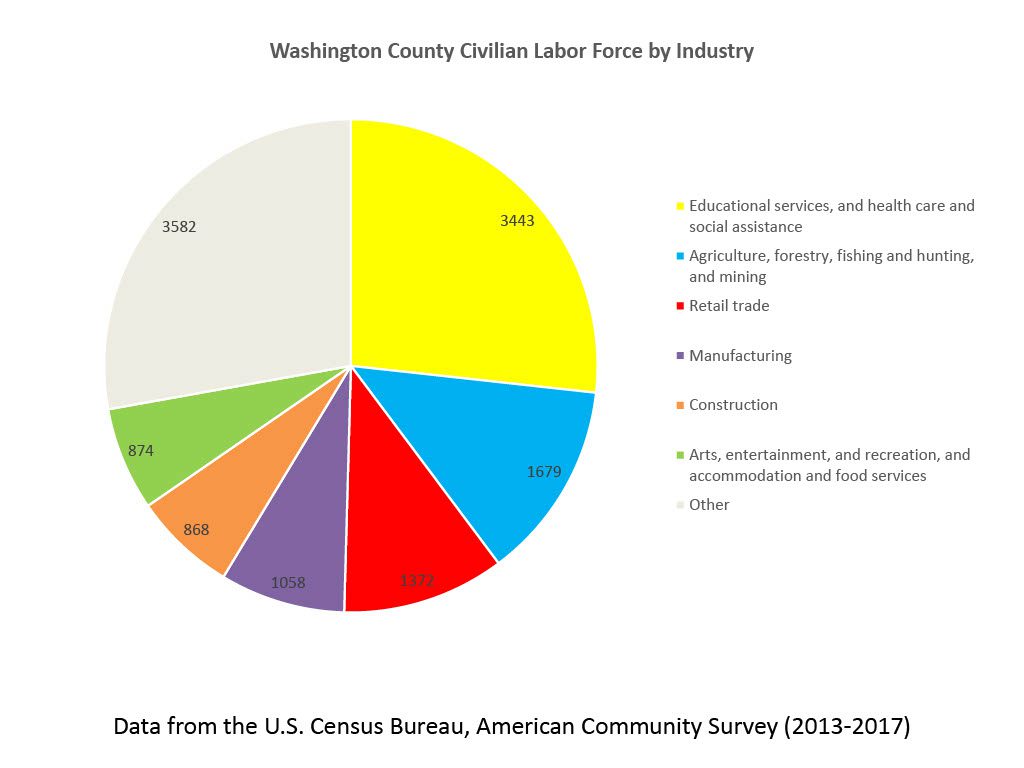

Education, healthcare and social assistance are the largest employment sectors, with 3,443 employed. Agriculture, forestry, fishing and hunting and mining come next with 1,679 workers. The retail sector has a decent showing with 1,372, followed by manufacturing at 1,058, arts, entertainment, recreation, accommodation and food services at 874, and then construction at 868.

Self-employment plays a major role in Washington County, with 3,582 — or about a third of the workforce — working for themselves, Rudelitch said. “It’s an important reminder of just how important self-employment is in Washington County — and small businesses.”

Poverty and wage statistics

Highlighting what many longtime residents of Washington County can attest to, Rudelitch pointed out that “the poverty rates here in the county are some of the highest in the state.” Washington County has a poverty rate of 18.2%, compared to 11.5% for the state as a whole.

Poverty affects some demographics more than others, with the elderly being less impacted due to “Social Security and the safety net that our society has constructed for the elderly,” Rudelitch said.

Families with children have some of the highest rates, capturing a third of all families. Female households with young children are the most affected, with 40% living in poverty.

“It’s a pattern you tend to see where poverty is most acute in single-parent households with younger children,” Rudelitch summarized.

Part of the county’s problem stems from low wages, particularly in comparison with the living wage necessary for the area. When calculating the living wage necessary for a family, Rudelitch said it effectively means a household that is “not relying on friends and family to provide essential services like childcare or help with housing or help with transportation.”

Two adults with no children working full-time will need approximately $52,000 a year for their household to meet all expenses, or $12.55 an hour each. One adult working full-time with no children requires $16.44 an hour.

For a two-parent, two-child household, the living wage required in Washington County is approximately $77,000 a year — to which Rudelitch acknowledged: “There are not a lot of jobs in Washington County that pay $77,000.”

For single parents, the living wage required per hour is even higher still to accommodate for high childcare expenses. One adult with one child needs $32.06 an hour for a living wage.

Women contend with additional challenges in lifting their households out of poverty in part because of the ongoing gender pay gap in the county. Some of the greatest disparities in wages in Washington County are in the professional, scientific, management and administrative fields, where women earn about $27,000 a year compared to men in the same position, who earn about $52,000.

Women lag behind men in every field, though those working in arts, entertainment, recreation, accommodation and hospitality make only $3,000 less per year than their male counterparts, who average $20,000.

Outside of gender differences, some fields in the county consistently offer living wages, Rudelitch shared. With 581 positions in the county on average, ambulatory healthcare services offer an average weekly wage of $959, followed by 437 hospital positions that pay an average of $1,160 a week. The best paid are those in the justice, public order and safety activities category, with 239 positions paying an average of $1,681 a week.

“A $1.5 billion economy”

Despite its economic troubles, Washington County still manages “an awful lot of economic activity,” Rudelitch said. Referring to the county as generally having around a $1.2 billion economy using traditional methods of determination, Rudelitch provided newer personal income data from the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis that show the county as having a $1.5 billion economy.

Not all of that money is spent in Washington County, however. A sizable piece — $653,853,000 — comes from government transfer payments, which includes Social Security, retirement benefits and medical payments on behalf of residents. The last category, medical payments, represents $280 million paid to vendors and service providers; this category has been growing the fastest over the past several decades.

“If you think of the economy as a flowing river about income, [medical benefits] are just a huge part of that income stream,” Rudelitch said. “We believe a great deal of this has been spent outside the county.” He added that the payments are going to pharmaceutical companies for prescriptions or to medical service providers in Bangor, Portland and Boston.

Aside from the $650 million in transfer payments from the government, the remaining portion of the $1.5 billion economy comes from wages — at just over $630 million — and investments. While that indicates that there is robust money generated in Washington county, it doesn’t reflect how much is spent here.

Restaurants and lodging

One measure of economic health for an area is its hospitality industry — and, after a difficult few years during the pandemic, sales at restaurants and accommodation businesses have recovered, Rudelitch stated.

Between Washington and Hancock counties, the combined hospitality industry is close to $500 million a year, with close to $300 million a year being spent in the Bar Harbor area. “We are adjacent to a huge amount of economic activity here,” Rudelitch said.

In Washington County itself, the combined total for 2022 is closer to $50 million, with Calais leading at $16.2 million per year and Machias right behind it at $16 million. Eastport accounts for $7.5 million of sales. For each city, annual sales are 50% higher than they were in 2007, though inflation accounts for some of the variance.

Even while the hospitality industry is a vital one for the area, it struggles with extreme seasonality, Rudelitch said. Being able to meet the need for employees each summer while still dealing with slow winters is difficult, especially for small businesses.

“There’s many times more economic activity in the summer than the rest of the year,” Rudelitch said. “But I think it is somewhat unnatural for an economy, and it’s a real challenge.”

Natural resources and aquaculture

With more than 1,600 residents employed in agriculture, forestry, fishing, hunting and mining, the county’s natural resources are an important source of its income.

For fishing, lobster, softshell clams, scallops and elvers are the primary catches. When looking at the combined value of those catches, more than 80% of it comes from lobster in any given year. “We are just highly dependent on lobster,” Rudelitch said.

Lobster catches have been “incredibly erratic” in the last few years, in part due to the pandemic, and in part due to changing climate conditions that are causing lobsters to move north. In 2021, more than $120 million in lobsters were caught, but in 2022, it fell to $54 million.

“It’s hard to overstate [lobster fishing]’s importance for Washington County as an industry that has been in a boom for a while, and now it’s really hard to tell where the trend lines are going.”

While data is not available on the salmon industry, Rudelitch said that based on public statements from Cooke Aquaculture, their landings are “immense, $80 to $100 million a year. So they are a major player.”

Rudelitch also provided that the value of wood products made at St. Croix Tissue and Woodland Pulp and exported through the port of Eastport is “perhaps $300 or $400 million,” adding, “It’s a major part of the manufacturing sector in Washington County and a major part of the overall economy.”

Touching briefly on blueberries, Rudelitch noted that there were “really hard years” for blueberry farmers between 2016 and 2020, followed by a recovery in 2021 that looks like it will continue for 2022. “It’s an iconic industry, very impactful in western Washington County,” he summarized.

Housing crunch examined

One of the more complicated categories Rudelitch and his colleagues are working to understanding is what’s happening with the housing stock of Washington County. “Why is there no inventory for sale? Why are there still vacant buildings?” he posed rhetorically during the presentation.

Demand is significant, creating “a lot of pressure and different forces” in the housing stock. Paired with the limited data currently available, it’s difficult to get a clear picture of what’s going on.

With that said, Rudelitch shared what is known. In 2018, the value of the housing stock in Washington County was $1.5 billion. Of that, $1.4 billion was represented by single-family homes. The next largest category after that was mobile homes, which is another kind of single-family home. Multi-family apartments are a very small part of the housing stock.

In the past few years, Rudelitch believes that the primary change in housing stock has been from year-round single-use homes to seasonal use homes, which is “where we really see the collapse of the inventory.”

RELATED: Housing shortage leaves Washington County residents scrambling

As more year-round single-family homes are being converted to seasonal-use homes, it’s putting a crunch on potential places to rent. As a result, Rudelitch said, “there are almost no units available at the HUD fair market rent level in Washington County.”

House sales have been skyrocketing in the county, having “exploded in the pandemic,” Rudelitch said. They slowed in 2022 “largely due to a lack of inventory rather than a lack of demand.” In 2019, house sales for the county were just under 400; in 2021, more than 620 houses were sold.

In accordance with demand, the average selling price of homes has gone up as well. In 2019, the average sales price was just under $150,000; in 2022, it was closer to $210,000.

“We are definitely looking at a place where there’s a lot more demand for housing in Washington County than we’ve seen in recent decades. And the prices are definitely showing that and the lack of available inventory. It just kind of shows that real mismatch between supply and demand in housing in the county.”

Rudelitch added that he saw mobile homes as being a possibly significant part of the solution for the housing stock, especially if there were incentives for reducing the costs involved.

“A lot of the housing development we’re going to see in Washington County in coming years, if the demand remains as strong as it is, is in single-family [homes].”

Another possible solution is in retrofitting old and historic properties, though Rudelitch said that path on its own would be ultimately “insufficient to create the type of housing we will need unless demand changes, and primarily unless demand for seasonal homes here changes.”

With the housing crisis in full swing, a multiple-pronged approach is needed, Rudelitch concluded. “I think we’ll need quite a few new housing units to bring the market back into normal functioning.”

Sign up here to receive The Maine Monitor’s free newsletter, Downeast Monitor, that focuses on Washington County news. This article is republished by The Maine Monitor with permission from the Quoddy Tides.