COLUMBIA FALLS, MAINE — Every morning, fantasy author Sheri Murphy wakes up and updates her Facebook friends on life in the quaint Downeast Maine community she’s called home for nearly two decades.

She extolls the charm of the river rushing through downtown, the towering balsam fir outside her window, the vast forests in all directions, and the area’s seclusion from the bustle of city life.

“I always tell them how beautiful it is here,” said Murphy, resting her hand on her Maine Coon cat, Baby Basil, purring softly in her lap.

“This is not a place for consumers. It’s a place for artists and writers.”

But what would become of this picturesque community if a powerful local family’s proposal to turn hundreds of acres of wilderness into a billion-dollar patriotic theme park — complete with a flagpole that, if built, would be the third tallest building in America — moves ahead?

Murphy and the nearly 500 residents of Columbia Falls have been grappling with that question since the Flagpole of Freedom Park, a business venture to “unite America,” was unveiled last year.

Concerned about the scale of the plans, residents of this enclave are preparing to hit pause on the attraction, arguably the largest and most eccentric project ever pitched for the Downeast region.

On Tuesday, residents will vote on whether to pass a 180-day moratorium on all large-scale developments in town, a move that could stall the record-setting flagpole plan and its surrounding amenities. Enacting the measure would buy them time to weigh the economic boon the park might provide against the disruptions it could bring to the scenic landscape.

The park is the passion project of the Worcester family, best known for its nonprofit Wreaths Across America, which places garlands mostly grown on their land in and around Columbia Falls at veterans’ graves nationwide every Christmas.

The project has lagged, and the family said Friday that it would return funds sent by donors over the past year to kickstart its construction.

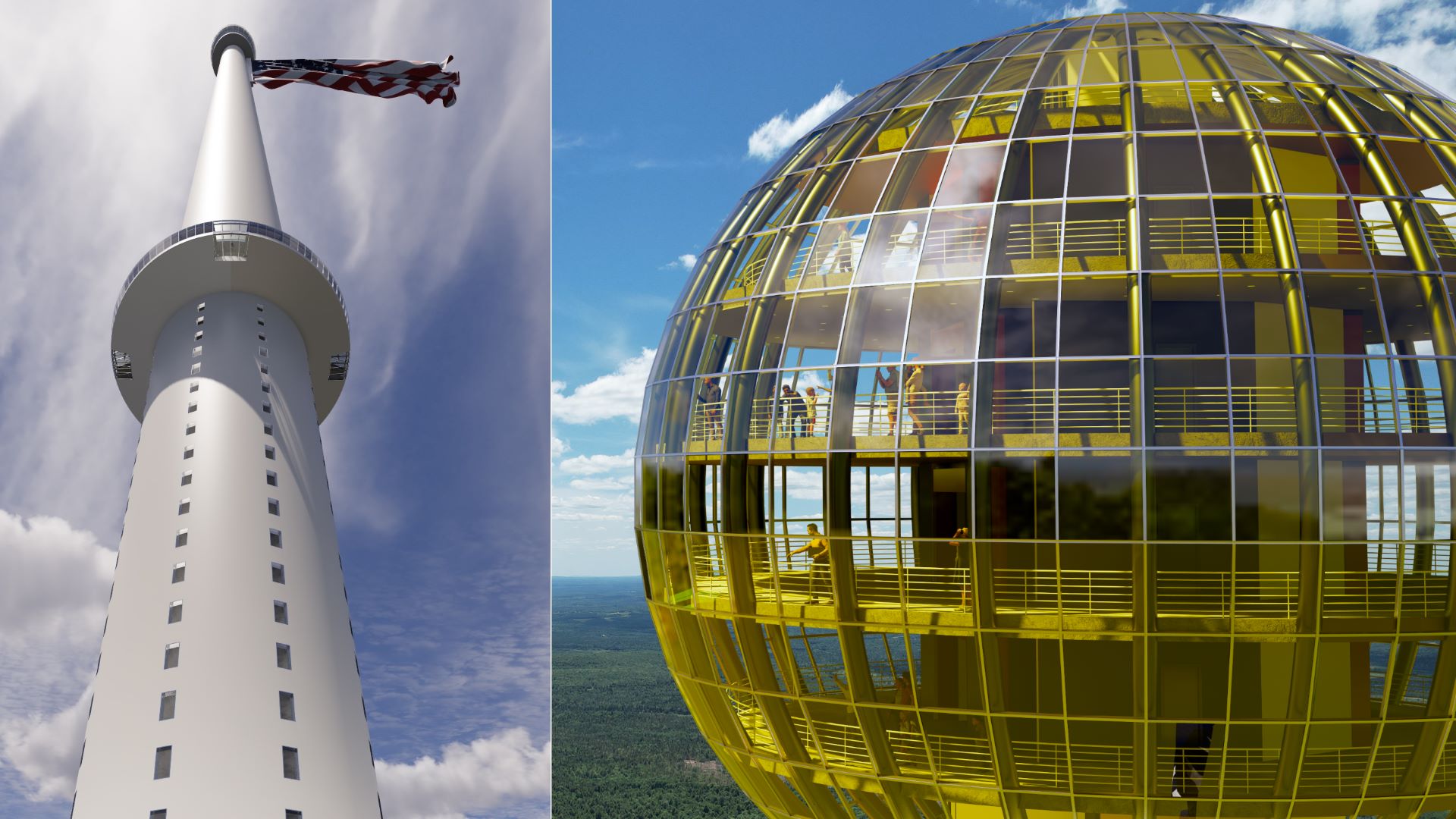

But if built, the Flagpole of Freedom Park would take the family’s mission to honor veterans to new heights. Its namesake flagpole would soar 1,461 feet high (exactly 1,776 feet above sea level), and become the tallest in the world by several hundred feet. It would fly an American flag the size of one-and-a-half football fields.

The pole itself would be a multistory building topped by an observation deck with views of Maine in all directions.

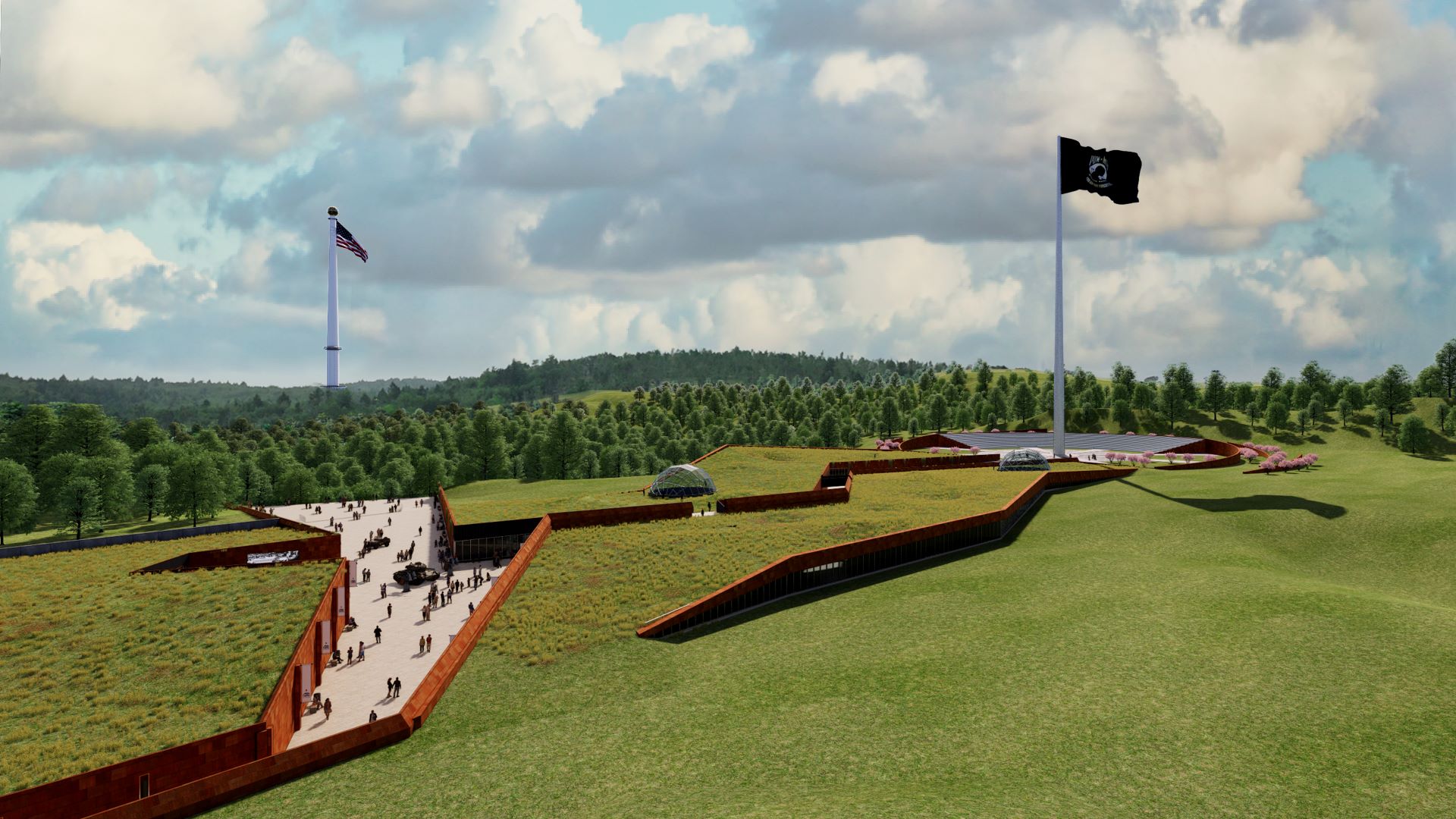

The surrounding park, as envisioned by the Worcesters, would feature theaters, restaurants, a hotel, stores, hiking trails, museum exhibits, and ticketed rides and educational attractions like the “Halls of History” and “Village of Old Glory,” that tell the story of the nation’s wars. Visitors would be ferried on gondolas criss-crossing above the trees.

In an area free to the public, “Remembrance Walls” nine miles long would list the names of every US veteran who has died, an exhibit that would be updated each year.

“This will be a place that’s known as the most patriotic place there is,” Rob Worcester, the project’s cofounder and managing director, said in a promotional video last year.

Critics have dismissed the Worcesters’ aspirations as fanciful and over the top. But for residents of the state’s poorest county, it’s a prospect that some say deserves serious consideration.

The median household income in Columbia Falls is roughly $47,000. Jobs are scarce, the nearest hospital is half-an-hour away, and going out to dinner is a 45-minute drive in both directions.

The region has long struggled to attract workers, and out-of-state investors who flocked here during the pandemic have worsened an already devastating housing shortage.

Nancy Bailey, who raised two children in Columbia Falls, has seen the toll a lack of opportunity has taken on her community. For many, the only way to make a living is to leave.

“We need something here — we desperately need something,” said Bailey.

She said she loves the area’s evergreen vistas and bright stars as much as other residents, but welcoming a tourist attraction of this size could help the community stay afloat.

Plus, she trusts that Morrill Worcester, the family’s patriarch, has Columbia Falls’ best interests in mind.

“He is a Columbia Falls man through and through,” Bailey said. “He wants the town to be taken care of.”

The family says the concept could create 5,000 jobs, which would make it one of the state’s largest employers. They’ve estimated it could attract 6 million visitors a year — 2 million more than Acadia National Park — and improve local infrastructure in need of repairs.

Nevertheless, the pitch has been a lot to swallow for Columbia Falls, whose business community consists of farms; a diner; a general store; a lobster trap manufacturer; and Wild Blueberry Land, a blueberry-shaped shop and museum.

“It’s just too big for the area,” said Dell Emerson, who has run Wild Blueberry Land, a roadside attraction, with his wife, Marie, for two decades.

Emerson, born in Columbia Falls in 1935, has watched the area turn from a bustling rural community to a sleepy town of mostly retirees. Although he believes the flagpole park is “a good idea,” he’s unsure his hometown is the right fit.

“I don’t think the facilities that we have in the town could handle an influx of 5,000 people,” he said.

Those fears were reflected in an anonymous survey that local officials asked residents of Columbia Falls and nearby towns to take this month. Asked if they would support a moratorium on large-scale development projects, more than 80 percent of the 193 respondents said “Yes.”

While people weren’t specifically asked about the flagpole project, many criticized it by name.

“We don’t have the capacity to support such endeavors as a community,” one person said. “Even a shopping mall would be a stretch.”

Others were worried about obstructed views, or the disruption of the “small hometown feel” and “natural beauty” that drew them to the area.

“It appears money makes right in Maine,” another person wrote. “If someone has a little money they can decide to ruin a town for all the town’s people.”

Another dismissed the flagpole project as “a giant tourist trap” that would “destroy” the “character of the town.”

The Worcesters have acknowledged concerns about their plans.

“There’s a lot of people that don’t want change,” Rob Worcester told The Maine Monitor last May. “But I think that [Washington County is] economically struggling a little bit and I think we can help.”

A smaller but equally passionate group of survey respondents seemed to agree with that sentiment, and were in favor of letting the project — and others like it — move ahead.

“It will not just line the owners’ pockets, it will in fact boost all local business traffic,” one proponent wrote. “Being one of the poorest counties in Maine, we could certainly use an attraction for tourist money.”

Another Columbia Falls resident derided a moratorium as “an evasive tactic” standing in the way of progress. Their number one concern? “Jobs, jobs, jobs.”

The project has been controversial from the start. It even came up during last year’s state Senate race. Asked for their opinions on it during a debate, candidates on both sides expressed skepticism.

Marianne Moore, a Republican who ultimately won the race, said it “looks awesome.” But she also questioned if it was “going to fly” in Washington County.

Her opponent, Democrat Jonathan Goble, had more disparaging words, casting doubt on how big of a draw it would be.

“How many times do people go to see the world’s largest pig?” he said.

Regardless of where residents stand, town officials, who are paid a small stipend and serve part time, have scrambled to wrap their heads around the infrastructure investments the project would require, as well as how traffic, recreational spaces, and natural resources would be affected.

It has prompted them “to assess what tools the town has in its toolbox to mitigate the impacts of commercial development,” said Aga Dixon, a lawyer and land-use planner the town retained to address the park proposal.

The town has already spent nearly $40,000 in consulting fees linked to the project. The Worcesters have covered $30,000 of those costs.

Much of the land where the park would be built sits on unorganized territory and falls under the purview of the state Land Use Planning Commission. The Worcesters want the town to annex it, which would speed up permitting and ensure taxes from the park go to the town. Residents would get a vote on that, as well.

If a moratorium is passed, it wouldn’t stop the project in its tracks. While a lawyer for the family said in December that it “could be devastating” because it might scare off potential investors, family members have suggested they’d build the park with or without the town’s backing.

“If a moratorium is what the majority of residents and municipal officials want to happen in Columbia Falls, that is up to the people of Columbia Falls,” Rob Worcester said in October. “Either the state or another municipality will reap the social, tax, and economic benefits should Columbia Falls choose not to support the annexation.”

Still, getting support from the community would smooth the path to opening.

The Worcesters initially planned to raise funds online from thousands of individual “founders,” as well as from large corporate sponsors, and break ground on July 4 this year. The aim was to open to the public in 2026, on the country’s 250th birthday.

In a statement Friday, co-founder Mike Worcester said the family was “in the process of returning” donors’ money given the delays, but he added that the Worcesters “remain committed to moving this project forward.” A fundraising page on the project’s website, which offered perks to those who pledged to make monthly contributions, is no longer functional. The Worcesters have not said how much money they have raised or plan to spend themselves on the project.

The family was once so confident about the project’s future that they built dozens of cabins on property overlooking the planned construction site, called Flagpole View Cabins. (Worcester Holdings was issued violations for doing so without proper permits).

After last year’s initial burst of publicity — which attracted attention from Fox News and other media outlets and included support from former presidential candidate Ben Carson — Columbia Falls residents say the Worcesters have gone mostly silent.

In the statement Friday, the family said it was reconsidering its approach to the park, but would not run it as a nonprofit. Mike Worcester said that while they don’t plan to fully go that route, the family has been working with veterans groups “to make our business model as inclusive as possible to receive their endorsement and support.”

Until then, Columbia Falls seems poised to buy itself some time, at a moment when investors have pitched big ideas for the Downeast region — among the last undeveloped sections near the coast in the US — including for solar panels, fish farms, RV parks, even aerospace ventures.

“Historically, the Downeast region has not been targeted for massive development, but that’s changing,” said Dixon. “It’s a bit of a wake-up call for these small communities.”

Sign up here to receive The Maine Monitor’s free newsletter, Downeast Monitor, that focuses on Washington County news.