Today I’m bringing you two interesting fishy stories that have crossed my desk recently — stories of two watershed moments at Maine dams.

A final fish count in Calais, a reopening river in the Passamaquoddy homeland

Since 1981, during seasonal fish runs from the sea to inland spawning grounds, observers have kept weekly counts of the fish passing through the fishway at Milltown Dam on the St. Croix River between Calais and Canada — until now.

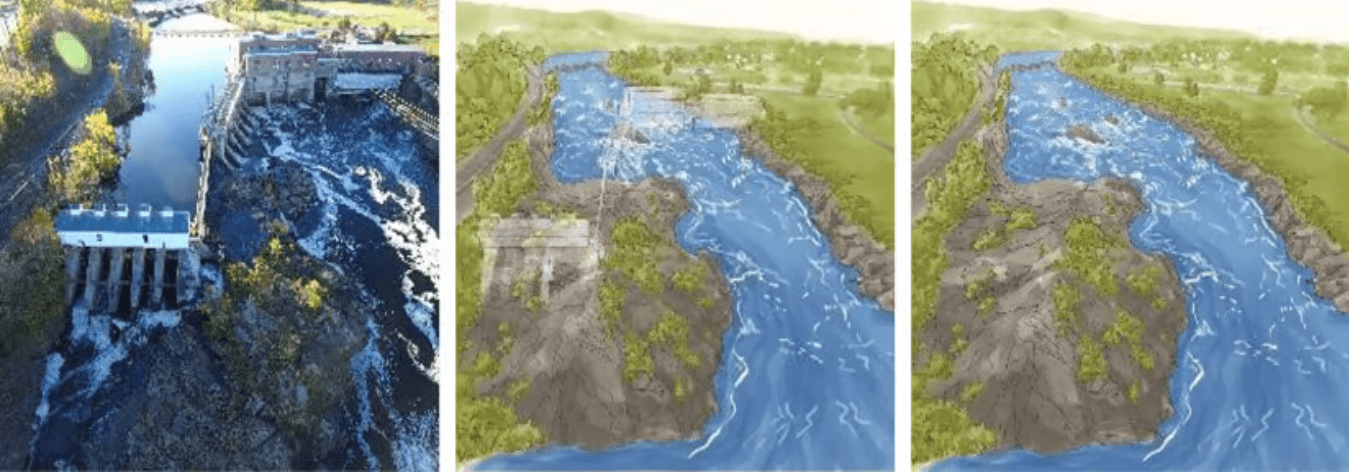

The St. Croix International Waterway Commission, a nonprofit, issued its last-ever fish count for the dam in late June. Milltown, which is owned by New Brunswick Power, is being decommissioned. Its demolition, first considered in 2017 and said to be one of the first conducted on an international boundary, began this month.

The dam was built in 1881, making it one of the oldest hydropower stations in Canada (though quite a small one at just 4 megawatts of capacity). It sits close to the mouth of the river, and its removal will clear the way upstream for sea-run fish like herring and alewives — key species for the ecosystem and for the people that have relied on that ecosystem for thousands of years.

“(The dam) is this major obstruction sort of in the heart of Passamaquoddy ancestral homeland,” said Tim Binzen, the regional tribal liaison for the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, in an interview with Climate Monitor this week.

The dam’s removal stems from a 2016 agreement between U.S. and Canadian agencies and adjacent tribal nations. The state of Maine joined an updated agreement last year, pledging cooperation in restoring the river and its fish runs.

“The removal of any dam on the river would be a big help in this effort, and especially in Milltown,” he said. “You want to start with the downstream dams first, ideally, because that opens up all the habitats and tributaries all the way upriver to the next dam. So this will be a really positive thing.”

Upstream from Calais, the river connects with the Moosehorn National Wildlife Refuge, where tribal leaders have worked with federal agencies on other aquatic connectivity projects.

Since the Milltown Dam’s fishway was improved in 1981, according to the state, the fish counts have shown a resurgence of river herring in the waterway, with generally more passing through the fishway each year — peaking above 836,000 so far this year in the final count in June.

But it’s a fraction of the species’ potential — the river is estimated to be able to support 20 million river herring, which officials said late last year “would double the number of river herring returns to the entire State of Maine.”

“It is important to understand that alewives (Maine’s more common kind of river herring) tie our ocean, rivers and lakes together, providing vital nutrients and forage needed to make healthy watersheds,” the state says on its fisheries website. “Between and within those various habitats, everything eats alewives.”

A federal grant awarded last year will help create an upgraded fish elevator at what will be the next-lowest dam on the river once Milltown is removed, according to Maine Public. The state’s director of sea-run fisheries, Sean Ledwin, said at the time: “This could be the largest river herring run in North America.”

As the Milltown dam removal gets underway, the river and its human stewards will enter a new era on the way toward realizing that level of restoration.

A dismal picture for eels at Millinocket dams in relicensing

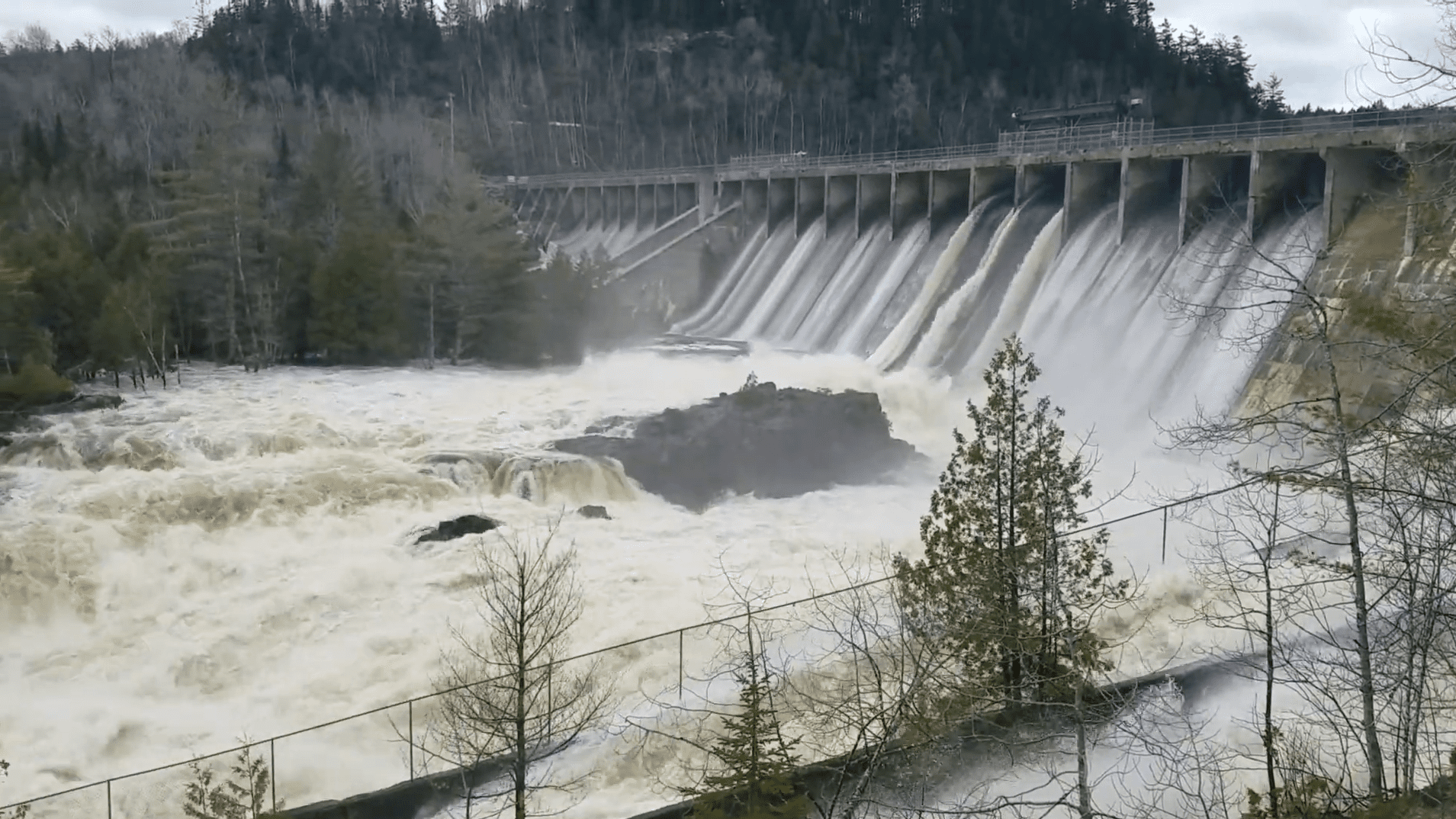

A set of five hydropower dams on the Penobscot River around Millinocket — one called Ripogenus and four more comprising the Penobscot Mills project — are currently undergoing a complex, years-long federal relicensing process.

They were built between 1846 and 1916 (that’s according to a neat project run by a few New England universities called the Dam Decision Toolbox) to power the now-defunct Great Northern Paper mill — once the largest in the world and the reason Millinocket itself exists.

All six dams are owned by Great Lakes Hydro America, a subsidiary of Brookfield Renewables. In terms of power generation, at a combined 108 megawatts of capacity, these dams are the largest such relicensing effort currently underway in Maine, according to comments filed in the case by the Maine Council of Trout Unlimited.

It’s also important to note that these dams have no fish passages built in.

Environmental groups, anglers, rafters, local residents, and other observers see relicensing as a generational opportunity to open the books on a dam’s operations and seek important changes.

For the Brookfield dams in Millinocket, in May 2022, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission ordered a wide-ranging set of 20 studies about the dams’ operations and effects on the environment and river users.

Now, Brookfield has released its first results for those studies and met with stakeholders this past May to discuss the results (see the PDF). For Landis Hudson, executive director of Maine Rivers, one study in particular jumped out: Appendix I, “Desktop Downstream Eel Passage Route and Survival Study.”

Eels are catadromous — they live in freshwater and migrate to the salty sea to spawn. (Alewives and salmon are the opposite, anadromous.) This means eels’ outmigration, downstream, takes them to their spawning grounds. Hundreds of eels have commonly been seen downstream of the Penobscot dams.

Brookfield responded to requests for comment after this story was initially distributed in newsletter form. David Heidrich, the company’s stakeholder relations manager for the Northeast, said eel restoration in the West Branch of the Penobscot has not been a priority for regulators in past licensing efforts, since the species can access the East Branch of the river.

“However, this situation has been steadily changing as downstream improvements to eel passage at hydro dams have resulted in larger numbers of eels moving higher and higher in the river basin,” he said.

Hence the need for this desktop study, he said. It used computer models, the dams’ specifications and data from other sites and studies to estimate how many American eels would survive a downstream passage through the projects, and how many would be fatally struck by the blades of the dams’ spinning power generation turbines.

“The vast majority of eels that would be migrating through the system were expected to be killed,” said Landis Hudson in an interview with The Monitor. “I found that, and continue to find that, disturbing and frankly upsetting.”

The numbers are, in the words of Trout Unlimited’s comments, “abysmal.” Eels starting in the Ripogenus dam impoundment would have to pass through five of the dams before they’d be in the clear. Only 6.4% were expected to survive.

“Since there is neither upstream nor downstream passage (for fish through the dam), the results are not surprising,” said Brookfield’s Heidrich, “and the purpose of the study was to begin to identify what passage measures may need to be considered as part of our ongoing relicensing efforts.”

He said it’s part of larger, ongoing discussions of restoring sea-run fish to this part of the river, with relicensing for these dams only now “beginning in earnest.” Heidrich also emphasized the dams’ role as a renewable energy source to help Maine reach its climate change goals.

Hudson, with Maine Rivers, did feel surprised and dismayed by the new understanding of the dams’ incompatibility, in their current form, with eels’ downstream migration.

“It seems clear to me that the potential habitat for American eel within a large part of the Penobscot watershed is not being considered in a way that it should be,” Hudson said. “It’s not being managed. … If these were more charismatic creatures, it would probably be more of an outcry.”

American eels aren’t endangered, Hudson said, but their lifecycle involves a dangerous journey even without hydroelectric obstructions. They’re part of a high-value fishery in Maine (for elvers, baby eels) and also play a major ecological role, like river herring, because of how they link the ocean and land.

“They’re not warm and fuzzy. They’re mysterious, they’re a bit slimy. Not everybody feels their heart sing when they think of eels,” Hudson said. “But they are very, very important… to tying the Gulf of Maine together, and having healthy systems for life to continue.”

The Sargasso Sea is an especially important place to be tied to — bounded by Atlantic ocean currents that circulate to form a gyre, rich in nutrients and biodiversity, and topped with a “golden floating rainforest” of seaweed that acts as a nursery for turtles and fish, including American eels.

In Millinocket, the eels could in theory pass safely through the dams’ spillways. They do this with a near-100% survival rate at other dams in the Northeast, according to the study. But it was deemed unlikely that any of the Millinocket dams would be routing any water into their spillways when eels are migrating.

Solutions are likely to be expensive and complex, Hudson said. But these are only Brookfield’s initial studies, with more to come.

“We look forward to working with GLHA (the Brookfield subsidiary that owns the dams) to identify protective measures to increase cumulative survival at these projects,” said Sean Ledwin, Maine’s sea-run fisheries director, in his comments on the eel study. He joined other stakeholders in calling on Brookfield to study “ramping” at the dams to help address this and other issues.

Ramping would mean changing the rate of water flow through the dams more slowly and gradually. Right now, stakeholders say the dams appear to be “peaking,” where water is released on-demand to meet electricity demand. Stakeholders said this approach can strand and kill fish and do other damage.

There were numerous other concerns raised in the comments on the study report in the past few weeks — on Brookfield’s approach to surveying local recreation users, on flood control and river level monitoring around the dams as the climate changes, on the lack of outreach to the Penobscot Indian Nation in the initial environmental justice study (Brookfield said at the May meeting that it was planning this outreach later this year).

The complexity of these projects shows exactly why relicensing and removal efforts can have such sprawling implications.

“Dams represent a literal and figurative nexus,” in the words of the University of New Hampshire researchers behind the Dam Toolbox: “a juxtaposition of infrastructure and freshwater ecosystems; an icon of technological innovation, economic prosperity, and cultural identity; a source of clean energy, opportunity for recreation, and threat to biodiversity.”

Editor’s Notes: This story was updated to include comments from Brookfield Renewables, which owns the Millinocket dams. Due to incorrect information provided to the Monitor, a previous version of this story used a photo that did not correspond to the Millinocket dams; the photo has been replaced. A previous version of this story incorrectly stated the agency responsible for the fish counts at the Milltown Dam.