Near the edge of Washington County, a city once defined by its porous border with Canada is contending with a substantial decrease in international crossings.

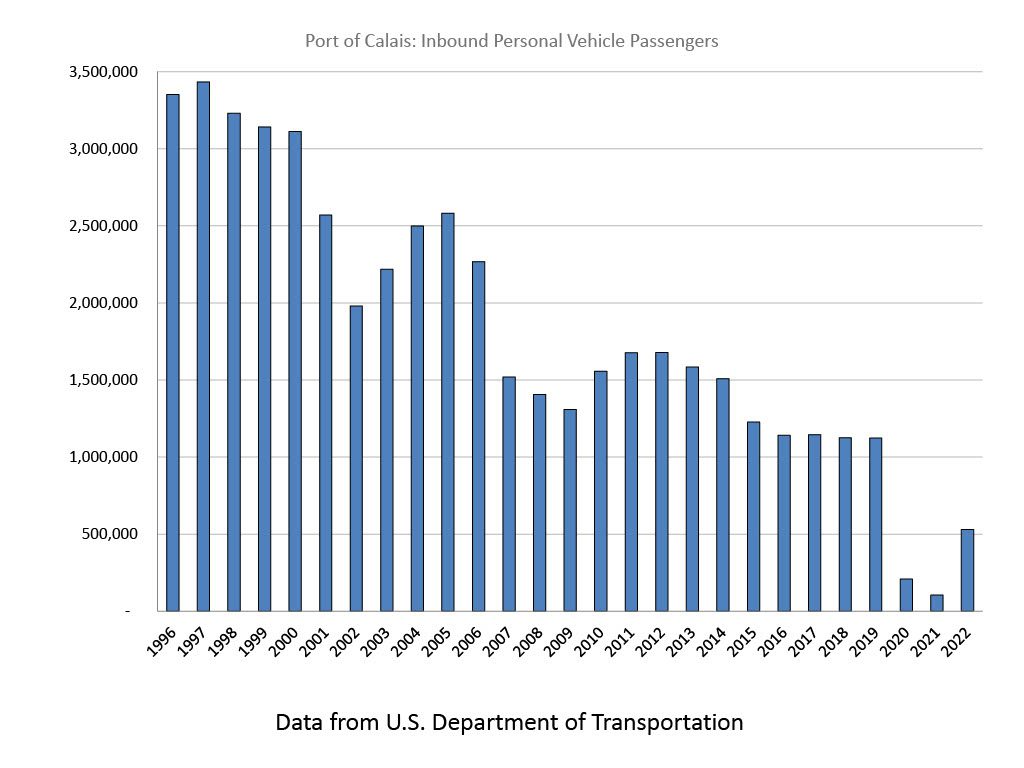

The slowdown at the Calais border crossing is tied most recently to the pandemic, with crossings the past few years far below the 1 million or so recorded in 2019.

The pandemic-era border tightening resulted in just 105,000 incoming passenger vehicles in 2021, the lowest on record, according to the U.S. Department of Transportation. Calais was hit hard by the loss of Canadian traffic and some businesses closed permanently, including one of the oldest restaurants in town.

The easing of Covid restrictions restarted some of the flow, and residents and businesses are reporting an almost-normal level of Canadian traffic. There’s a long way to go, however: Crossings in 2022 were just over 530,000, and in 2023 only 135,000 were recorded as of early May.

The recorded peak was in 1997, when 3.4 million passenger vehicles crossed into Calais. Inbound crossings in 2019 were a third of that benchmark — signaling a rapid decline even before Covid’s impact was felt.

Not without irony, the pandemic has provided Calais with a few saving graces: New residents have moved in, some bringing new businesses and some working remotely — a feat made possible in part due to Calais’ well-timed broadband infrastructure project, completed in 2019. Along with the increased access to broadband, the expansion of telehealth due to the pandemic improved access to a range of healthcare services for the rural community.

Calais residents remain committed to being an international city, drawing from an impressive history of mutual development with St. Stephen, the Canadian community just across the St. Croix River. This year marks the 50th anniversary of the International Homecoming Festival, which once drew 60,000 visitors to a city that now numbers just over 3,000. While the parade once traveled between both cities, it hasn’t been able to make the crossing in years.

The reality of the tightened border is perhaps best summed up by John “Al” Churchill, who grew up in Calais in the 1950s and is president of the St. Croix Historical Society on Main Street.

“Sadly, we are never going back to being an ‘International Community on the St. Croix’,” Churchill said, referring to how Calais and St. Stephen were described for over a century in numerous national publications. “There are too many legal impediments and new barriers.”

To understand what the border slowdown means for Calais, it helps to rewind the clock to when there was no United States or Canada — only a waterway in far northeastern Massachusetts on the frontier of a developing civilization.

Calais in the early days

Part of the Passamaquoddy people homeland for 12,000 years, Calais saw its first international settlement when Pierre Dugua and his mostly French expedition landed on St. Croix Island in 1604 — a full three years before the landing at Jamestown, Va. After a deadly winter convinced the French settlers that the island wasn’t meant to be the site of New Acadia, they traveled farther up the coast the next year.

In the 1700s, the St. Croix Valley was a hotspot for fur traders and frontiersmen, including Daniel Hill, its first permanent settler. Arriving in 1779, Hill saw the drawing of the valley’s imaginary line between the newly formed United States and Britain — straight down the middle of the St. Croix River. Those loyal to Britain settled in what would become St. Stephen, and those loyal to the new republic remained in what would become Calais.

For many decades the border was, at best, a suggestion. “Officially a border did exist, but in practice the bonds between the inhabitants of the St. Croix Valley were stronger than those to the distant governments of either the United States or England,” Churchill said.

Families mingled freely across the border, and residents of both towns often commuted across the bridge to work. The valley’s lumber barons, who drove the prosperity of the region as fiercely as the horse teams were driven between the railroad and the docks, gained national notoriety in The New York Times in 1888 for their willingness to dodge taxes and tariffs while moving goods across the border.

Aside from the lumber barons, casual smuggling was freely practiced. “Duty and tariffs were rarely paid, and a customs officer who tried to enforce the law was likely to be ostracized or worse,” Churchill said.

The free sharing of goods and culture continued in the St. Croix Valley until World War II caused the first major slowdown in crossings. An article in Aug. 31, 1946 Saturday Evening Post by J.C. Furnas tells how “the good old days when the guardians of the bridge, Canadian and American alike, knew everybody in both towns and let them go back and forth as freely as if they were merely crossing the street, disappeared with a thump, and identification papers with photographs became essential and hard to get.”

While the war led to a slowdown at the border, it was short-lived, and the baby boom era saw a return to cross-border business. It would be over 50 years later before the border felt the powerful squeezes of government restrictions.

9/11 thickens the line

Following the Sept. 11, 2001 terrorist attacks, both the United States and Canada began implementing restrictions.

The effect was pronounced. Between 2000 and 2002, incoming passenger vehicle traffic at the Calais border dropped by a third, from 3.1 million to just under 2 million.

“Before 9/11, locals especially were just waved through with no questions asked and no documents required,” Churchill said. With both countries gradually enacting more restrictions over the next several years, the once-open border became buttoned up by the 2010s. “Now, every visit has to be logged on the border computer and a document scanned. It feels like you are entering a foreign country, not just crossing an imaginary line,” he said.

The economy takes its toll

While documentation requirements kept some travelers from crossing the bridge at all, others were willing to endure the paperwork and longer wait lines, especially if it meant being able to get goods cheaper on the other side.

Sometimes people traveled for services — whether it was healthcare, beauty care, leisure or fitness. St. Stephen was a much larger city by the 21st century — housing 10,000 residents to Calais’ 3,000 — but amenities were often scarce on one side or the other.

As such, Calais and St. Stephen businesses have remained tightly intertwined, and economic disruptions in either country have led to dramatic changes.

State Senator Marianne Moore, who opened a Curves location in Calais in 2004, enjoyed a robust Canadian membership of 35 to 40 people at her fitness studio following the closure of the St. Stephen Curves around 2008 — but only for a limited time.

“My Canadian membership remained very strong, tolerating the longer-than-usual waits at the border, until the exchange rate got to the point where it was costing them more to come to Curves than other gyms in St. Stephen,” said Moore, a former Calais mayor. By 2017, membership numbers fell so low that she had to close.

The total number of incoming passenger cars for 2019 was just 1.1 million. Although the number had plummeted by more than 67 percent in two decades, it would soon see its steepest drop yet.

The pandemic introduces problems and solutions

Borders around the world closed between 2020 and 2022 as governments sought to contain Covid. The effect in Calais was significant. Cross-border traffic fell to a trickle except for essential visits. (Inbound truck crossings, however, dipped to just under 60,000 for the year, which was a slight decrease from the average over the past decade.)

“Many Calais businesses were fearful that without the Canadian traffic they wouldn’t sustain,” said Kara Mitchell, executive director of the St. Croix Valley Chamber of Commerce.

In some cases, they were right: The largest business to close was the Label Shopper, a clothes store on Main Street less than a mile from the border. The Wickachee — considered by Churchill perhaps the oldest restaurant in the St. Croix Valley, opening in the 1840s — also closed.

It wasn’t just the lack of Canadian traffic that hampered businesses, said Dunkin’ manager John Cowell. “We were more affected with the Covid spread within our store than the border shutdown. The lobby was closed so we ran drive-thru only for a lengthy period of time.”

With fewer employees and steady demand, the drive-thru line was occasionally heavily backed up.

Local demand kept Dunkin’ afloat during the pandemic, and with the reopening of the lobby, a price increase and the marketing of better products, it’s back in good shape, Cowell said.

“We have been exceptionally lucky to maintain staff and business through the crazy times with Covid and the border closing.”

One key factor in keeping Calais businesses going has been the arrival of newcomers to the community. For years the population steadily declined, but the pandemic saw people across the country relocate to less populated areas that offered affordable work-from-home opportunities.

A new wave of residents

While it’s difficult to say how many people moved to Calais in the past few years — and how many moved out — the small population means it’s easy to spot new faces.

“We have gained a lot of new customers,” said Cowell of Dunkin’. Some started coming when the nearby McDonald’s was shut down for renovations, but others are entirely new to the area.

RELATED: New faces showing up Down East

Part of the appeal Calais offers newcomers is its inexpensive access to high-speed broadband internet. The service exists due to Calais’s novel partnership with Baileyville to the north; the municipalities worked together to create the Downeast Broadband Utility (DBU) in 2017 with a goal of lighting up the area’s dark fiber. With the Calais network widely completed by 2019, residents are making the most of the service.

Anne Perry, a Calais legislator who was among the first to have access to the DBU’s service, noticed during her campaign that residents were clearly using the service.

“I would be going door to door and people would answer and say they only had a few minutes because they were about to have a meeting,” she said.

Perry herself used the city’s broadband lines heavily during the pandemic, when legislatures held meetings virtually.

Perry, a career family nurse practitioner, views the combination of broadband and new access to telehealth as being key to attracting people to Calais and keeping its businesses afloat despite the pandemic.

Not all new residents came to Calais to work remotely — some came to open new businesses, joining local residents who seized the initiative to open their own ventures. In total, Calais has opened 15 businesses since 2015, according to Mitchell, “far outweighing the businesses that have closed.”

A flurry of new businesses

From the White Birch Exchange on North and Main to Mama Lola’s Mexican Restaurant and Boujee Bouj Skincare, newcomers have been opening businesses in Calais after choosing it as their new home, Mitchell said.

At the same time, residents have poured their own investments into the community in anticipation of demand as the area grows. “Despite the desolate border crossing, some businesses such as the Riverview Restaurant put considerable revenue into restoring the historic brick block buildings on Main Street, and even renovated the interior of the adjacent building to open Fox & Hen Pub,” Mitchell said.

Downtire Attire opened under the helm of Calais native Jamie Moholland; it sits in the former Clark’s Variety Store, long a community fixture. My Favorite Things 2 was opened on Main Street by the daughter of the owner of the original store, which closed in 2010.

Calais has “surprisingly” not seen any increased revenues since the border reopened, said City Manager Mike Ellis. There have been a “typical amount of building and change-of-use permits compared to last year,” and tax revenues have ebbed and flowed “with nominal residential development offset by diminishing old properties disappearing from the tax rolls.”

He adds, however, that the number of new small businesses popping up “is always encouraging.”

Calais today

With its border now open to those with proper documentation, Calais anticipates a gradual uptick in the number of passenger vehicles coming in as summer approaches. With 135,000 crossings so far this year, it’s a far cry from the city’s heyday, but the number doesn’t tell the whole story.

At Hardwicke’s, where its prime location just after the border crossing makes it a preferred stop for Canadians to buy less expensive gasoline and alcohol before returning over the border, “business is back 75 to 80 percent of where we were in 2019,” said store manager Bill Kilby.

Hardwicke’s is unique among Calais businesses because 85 to 90 percent of its business comes from Canada, Kilby said.

While Calais may never regain the border traffic it saw even a decade ago, its international flavor remains a vital part of the community.

In August, the city will coordinate with St. Stephen to host the 50th anniversary of the International Homecoming Festival. Its precursor, 1961’s International Frontier Week, was organized by the municipalities’ Rotary clubs; it attracted the Maine governor and the premier of New Brunswick, along with baseball great Ted Williams of the Boston Red Sox and tens of thousands of visitors.

A more modest and domestic affair in the modern era, this year’s festival will still boast a street fair, musicians, games, puppeteers, a raft race and more, all of which “helps out our downtown businesses, hotels and restaurants,” said Laurel Perkins, who is coordinating the Calais side of the events. St. Stephen will mainly organize its own festivities.

While the parade hasn’t been able to cross the bridge in years due to paperwork complications, the opening ceremony remains the Hands Across the Border event, which sees dignitaries and townsfolk of both communities meeting on the bridge to exchange pleasantries and flags. And the traditional finale of the festival, a grand show of fireworks — sponsored by Hardwicke’s — remains a highlight for residents on both sides of the border.

Sign up to receive The Maine Monitor’s free newsletter, Downeast Monitor, that focuses on Washington County news. Know of a Washington County story we should cover? Send us an email: gro.r1751317760otino1751317760menia1751317760meht@1751317760tcatn1751317760oc1751317760.