Paige Solans will graduate from the University of Maine School of Nursing this spring, but she’s been working part-time in a hospital intensive care unit for the last 10 months of the COVID-19 pandemic.

As part of her schooling, Solans took a course on handling patient death and dying. But it still was difficult to process the severity of illness and the amount of death she saw among COVID-19 patients in the ICU at Eastern Maine Medical Center in Bangor.

“I don’t think anything could have prepared me for that because I don’t think anyone could have predicted how much death we were going to see,” Solans said.

Despite experiencing the challenges facing healthcare professionals, Solans said she can’t imagine pursuing another profession.

“The type of resiliency I have now as a student nurse — soon to be nurse — I think that would have taken me years to build up otherwise,” Solans said.

Even as Maine hospitals worry about pandemic burnout and a nursing shortage, graduating nursing students like Solans are eager to work. So many new nurses have entered the field in recent years that a study this year found the projected statewide workforce shortfall for 2025 has shrunk in half.

Nationally, enrollment in nursing programs increased 5.6% in 2020, according to the American Association of Colleges of Nursing.

The University of Maine School of Nursing welcomed its largest class of incoming freshmen last fall due to an unprecedented number of qualified applicants, said Kelley Strout, associate professor and director of the nursing school. In a typical year, it admits 80 students. This year’s total is 120.

Strout attributed the increase to media attention on nursing during the pandemic and coverage calling nurses heroes.

The school also saw a 50% increase in first-generation college student enrollment, and a 340% increase in Hispanic and Latino students, Strout said.

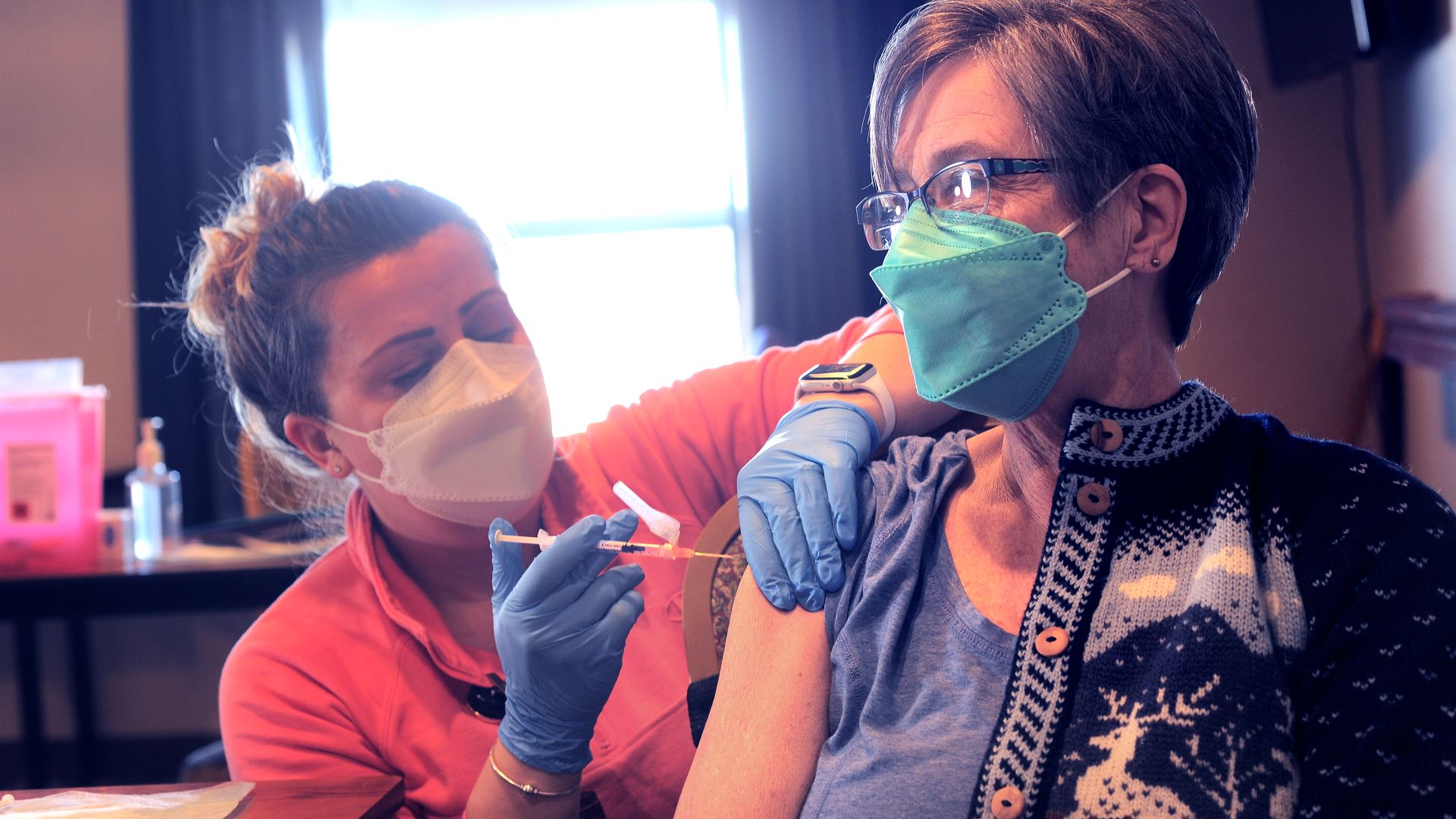

In addition, nursing students have been involved in Maine’s COVID-19 pandemic response. They’ve administered more than 12,000 vaccines at clinics, long-term care facilities, jails, schools and homeless shelters, Strout said. Students have responded to outbreaks and staffing shortages at hospitals.

“You name it, they did it,” Strout said. “Some students were fearful at times with a pandemic but never enough to drop out of nursing school. Fear is normal but we never saw a mass exodus.”

‘Everything’s COVID’

While there’s more interest, it’s also harder than ever to be a nursing student, Strout said. She has seen unprecedented levels of stress and anxiety among her students.

Nursing already was a rigorous field, but social distancing, gathering restrictions and mask mandates made it difficult for students to decompress, she said.

Solans was a sophomore when COVID-19 was detected in Maine. She remembers her lab on the fundamentals of nursing switching from a hands-on class to online. Instead of learning to put in a catheter on a mannequin, Solans had to demonstrate over Zoom with a toilet paper roll taped to a teddy bear.

“It was just one of those moments that always stuck out to you. I’m like, ‘I will remember this forever,’ ” she said.

The pandemic made her classes feel more real. On the news, she saw nurses using isolation precautions she learned about to prevent transmission of infections. And when she heard about N95 mask shortages, Solans was alarmed because she recently learned the importance of those masks in handling airborne illnesses.

“You go to work and everything’s COVID. You come home and everything’s COVID. You go to class and everything’s COVID,” Solans said. “It was just like there’s no escape.”

Strout said she worries about the students’ mental health during this stressful time. It’s tempting to make classes and assignments easier for students, but the school needs to produce nurses who can withstand the demands of the profession, “and the demands have never been greater.”

To support nursing students, the University of Maine is offering summer courses so students can lighten their loads during the year without getting off track. The college also received a $1.7 million grant to teach stress-reduction techniques, fitness programs and nutrition workshops.

“We’re trying to balance the rigor and demands of the profession, and trying to support our students’ emotional well-being so at the end we’re essentially promoting graduating a more resilient product,” Strout said.

Workforce shortages

Maine previously was on track to have a shortage of more than 3,000 nurses by 2025. But an updated report commissioned by the Maine’s Nursing Action Coalition and the Maine Hospital Association found that annual increases in new registered nurses has reduced that projected shortfall to 1,450.

Strout said Maine’s nursing schools and healthcare system are working together to address the workforce crisis and support new students.

Solans said the biggest challenge causing burnout she saw in a hospital was staffing shortages.

“At the end of the day, you can have as much funding, equipment, everything, but if you don’t have the people actually there to do the care, nothing is going to get done,” Solans said.

However, one benefit of workforce shortages is more opportunities for new nurses to work on specialty floors. Solans thinks she has a chance of getting hired to work in an ICU when she graduates, which wouldn’t normally be an option for a new nurse.

Travel nursing

Louis Rosenthall, a freshman at the University of Maine, said he always knew he wanted to work in the medical field. His grandfather is a family practitioner, his grandmother was a school nurse and his aunt is a nurse at a Boston hospital.

“Growing up, hearing their stories about how they’ve had a positive impact on someone’s life or going the extra mile to help someone any way they can inspired me to go into this profession,” Rosenthall said. “Making a positive impact on somebody’s life every day just makes me happy.”

He was in high school when COVID-19 started spreading, but that didn’t deter him from applying to nursing school.

Rosenthall said he’s still figuring out which nursing setting he might want to work in, but he’s interested in becoming a travel nurse when he graduates as a way to see different places.

Strout said she’s heard more of her students, like Rosenthall, say they want to become travel nurses right out of school. These nurses move to a new community, typically for 13 weeks at a time, and fill in when there are staffing shortages or other short-term challenges.

They are becoming more of the norm when facilities struggle to hire full-time nurses due to workforce shortages. Travel nurses often get paid much higher salaries but are with facilities for shorter periods, which makes it difficult to form relationships with patients.

While some young nurses are attracted to the adventurous aspect, Strout said that’s not how the travel nurse system is intended. They are supposed to be experienced nurses who go someplace in a pinch.

“I’m all about nurses making a lot of money and I’m very pro improving working conditions for nurses and job satisfaction,” Strout said. “But I do not think this is a sustainable long-term solution, and I do not think it’s good for patient care or patient outcomes.”

Travel nurses don’t help produce the next generation of nurses because they aren’t with an institution long enough to train students.

There already is a shortage of faculty and training sites, which causes a bottleneck in the capacity to train incoming nurses.

Strout said her nursing school likely won’t admit another large class like this year’s because there aren’t enough faculty. So it’s important to increase the state’s supply of qualified nurses who can teach the next generation.

“It’s a matter of getting our faculty pool up and really emphasizing the need to get more nurses educated at a master’s degree or higher,” Strout said. “That is a critical component of this nursing shortage.”