Editor’s Note: The following story first appeared in The Maine Monitor’s free environmental newsletter, Climate Monitor, that is delivered to inboxes for free every Friday morning. Sign up for the free newsletter to get more important environmental news from reporter Kate Cough by registering at this link.

There’s been a lot of (well-deserved) attention paid in recent years to sea level rise and the havoc it is expected to wreak on Maine’s coastal and island communities. Up and down the coast, towns, cities and private landowners are building seawalls, raising buildings, replacing culverts and elevating causeways in an effort to keep the tides at bay.

While we’ve been busy fortifying ourselves above ground, another problem has been creeping up from below, one that’s less visible but perhaps poses a more immediate threat: as sea levels rise, the ocean is coming ever closer to the freshwater aquifers and fractures from which nearly half of Maine’s residents draw water for drinking, bathing and cooking.

“Saltwater intrusion is becoming a problem for peninsula and island communities in their wells,” said Gayle Bowness, who manages the municipal climate action program for the Gulf of Maine Research Institute, “not just for the people who live on that property today, but who may live there in the future.”

Because it’s dense, saltwater typically sinks below freshwater and stays there. But as the level of freshwater decreases (either due to drought or increased use), or the level of saltwater increases (with rising seas), the two can mix, creating a cloudy, salty brine.

“It’s a balance between the land and the sea,” Holly Michael, director of the Delaware Environmental Institute, explained to news outlet Circle of Blue earlier this month. “If you have enough freshwater on land, then it balances out sea level. But if you take away some of that freshwater by pumping it out, then that upsets the balance and the saltwater starts to move inland.”

Deeper wells and those that are in close proximity to others are most at risk, since they’re likely to bump up against the boundary between freshwater and seawater before shallower wells as sea level rises. The problem is also exacerbated when there are a lot of drilled wells in close proximity to one another, as there are in areas of coastal southern Maine.

At a recent meeting on Long Island in Casco Bay, Bowness spoke with a resident who knew several islanders whose wells had been ruined by seawater, forcing them to buy bottled water on the mainland for drinking, bathing and cooking. It’s hard to get a handle on the scale of the problem, however, since those who do have contaminated wells don’t have much incentive to speak up about it.

“That property then becomes a bit of a black sheep,” said Bowness, “because immediately their property value declines.” Drilling a new well costs between $6,000 and $10,000, with no guarantee the new one will be salt-free, and before the problem is fixed, saltwater can corrode and ruin pipes and fixtures that weren’t designed to handle the saline.

Long Island is not the only community in Maine to be worried about contamination of its drinking water. North Haven recently received a grant to conduct a hydrological study that will examine that issue and others, and neighboring Vinalhaven is looking into undertaking similar research. In Bar Harbor, one realtor said she’d had several clients with saline in their wells, all of whom had to abandon them and redrill elsewhere.

The thought of losing wells to saltwater is particularly worrisome in Stonington. Although contamination is relatively rare at the moment, as far as Town Manager Kathleen Billings is aware, it’s likely to get worse in the coming years, and the town is already dealing with a seasonal water shortage. This summer, said Billings, the town has been forced to truck in four or five tractor trailer loads each day to keep up with increased use by seasonal residents and visitors and several years of decreased precipitation.

“Ten years ago, if you told me we’d be trucking in water, I might think well, if we had a really bad leak, or something like that,” said Billings, who has lived on the island most of her life and said she “never in a million years” would have thought the town would have to haul in water from elsewhere.

Communities elsewhere in New England and further south are already struggling with the issue. A recent study conducted in Rhode Island found a number of homes with contaminated wells, some of them a mile or more from the coast. Florida, where many communities are built on what was once the salty marshland of the Everglades, has been dealing with the issue for decades. Three public water districts in Hilton Head, South Carolina have spent $129 million since 1998 trying to mitigate the issue by buying treated river water and developing alternative supplies; they estimate another $80 million will be needed before 2042 to continue replacing lost supply.

“We’re not prepared for what’s coming,” Thomas Boving, a professor at the University of Rhode Island, told ecoRI News.

The problem is not so dire in Maine just yet, but a 2015 paper on saltwater intrusion into wells in Casco Bay warned that it one day could be: “Saltwater intrusion poses a great risk to the residents of coastal Maine due to its relative permanence and difficulty to reverse,” wrote researchers, “especially for communities in which aquifers provide the sole source of drinking water.”

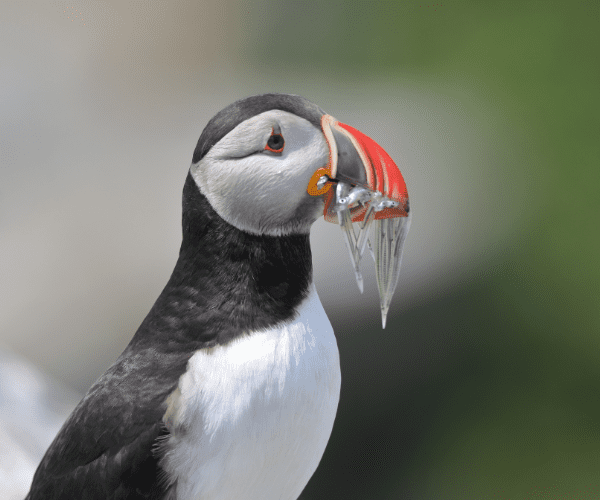

Journalist and author Derrick Z. Jackson knows puffins. He’s co-authored a book (“Project Puffin”) about the little seabirds and periodically returns to the islands off Maine to check on their progress. As he points out, puffins were in trouble, having been slaughtered for their eggs and their meat in the late 19th century.

This year, he has good news. He visited the island of Petit Manan, and found that puffins there are making a comeback, thanks to the work of a biologist for the United States Fish and Wildlife Service and others.

“Over the last half century, the bird has been restored from the brink of extinction in Maine, the only state where it breeds,” Jackson wrote this month for the Union of Concerned Scientists. “Petit Manan is important because it represents a unique and encouraging lesson in puffin restoration.”

To read the full edition of this newsletter, see Climate Monitor: As sea levels rise, saltwater intrusion threatens to poison Maine wells.

Kate Cough covers climate change and the environment for The Maine Monitor. Reach her by email with ideas for other stories at gro.r1752615638otino1752615638menia1752615638meht@1752615638etak1752615638.