Jennifer Noonan’s two sons are only two years apart in age, but their experiences with remote learning during the COVID-19 pandemic this spring were dramatically different.

Terry, 14, had “a great experience” at Buckfield Jr./Sr. High School. He received printouts of his homework every two weeks, which he completed independently and turned in with a sense of pride, his mom said.

Aedan, however, had a harder time in sixth grade at Hartford-Sumner Elementary School. He never received another packet of work after turning in the first one. Noonan declined a wireless hotspot from the school because she’s opposed to having internet in her home, but that made it difficult for her to communicate with Aedan’s teachers. Noonan emailed once to follow up but never heard anything more.

“I felt really in the dark and isolated,” Noonan said.

The lack of communication was two-sided, Noonan acknowledged. When she ran into Aedan’s teacher months later, she told Noonan that many students just disappeared during remote learning. Much of the material was review and since Aedan already had a good grasp of the concepts, the teacher said she wasn’t worried about him.

“She said. ‘I got in touch with Aedan way more than some kids,’ ” Noonan said. “Some kids just got lost. I think the teachers were really upset about that. She was like, ‘I don’t even know if they’re OK.’ ”

School officials and parents pointed to a variety of factors that determined whether a student was successful during remote learning, such as access to the internet and resources, structure and support at home, and the student’s motivation and willingness to ask for help.

But these varying experiences — even within the same household — could mean students will be in very different places with their education when classes resume this fall.

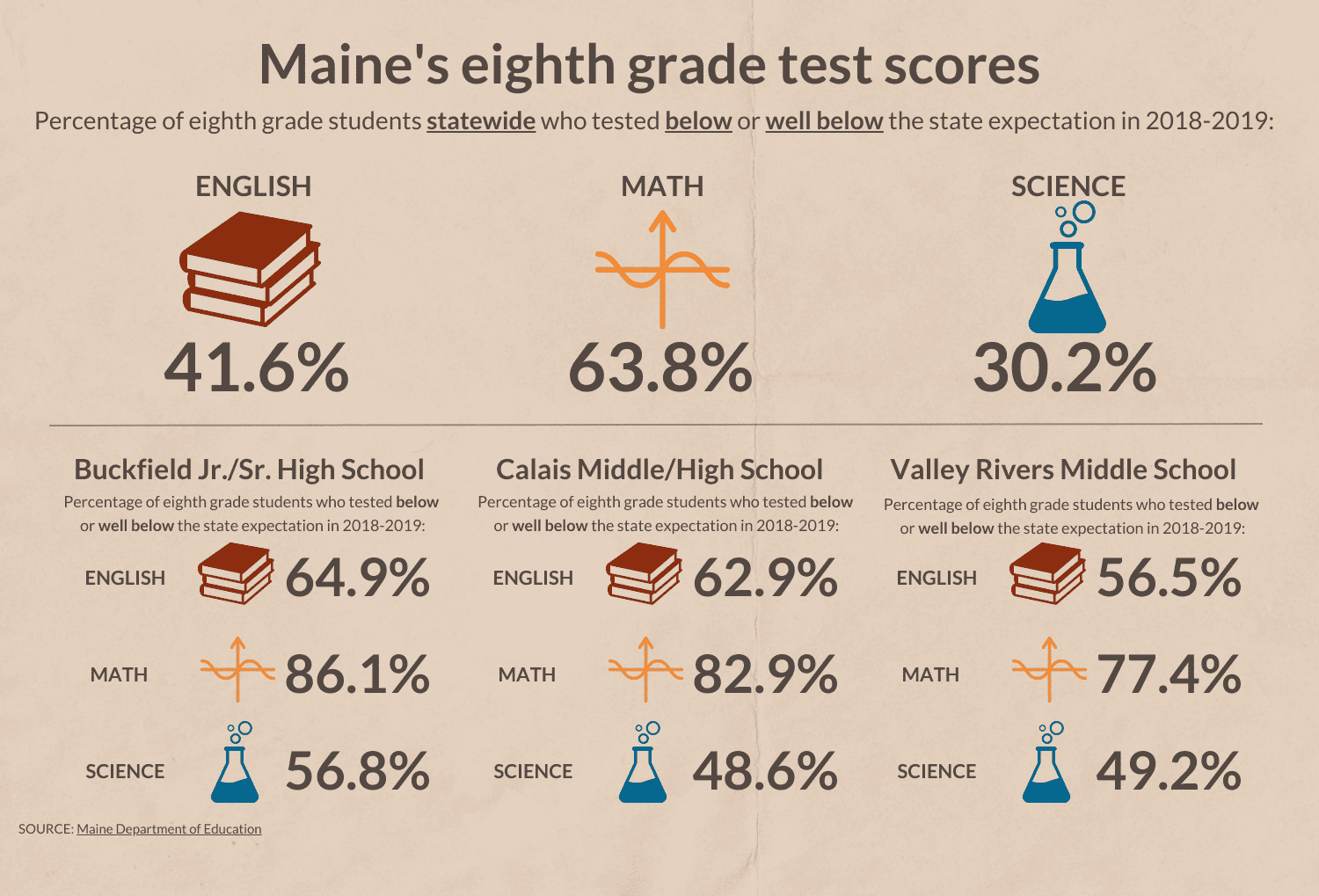

For schools like Buckfield, which had some of the lowest test scores for eighth graders in 2018-19, remote learning may have put students even further behind.

If students don’t return to in-person classrooms full-time until January 2021, existing national achievement gaps could increase by 15 to 20 percent, according to a June study from the management consulting firm McKinsey & Company.

In this scenario, the firm estimates the average student could lose $61,000 to $82,000 in lifetime earnings, which translates to an estimated $110 billion in annual earnings across the entire current K-12 cohort. Low-income, Black and Hispanic students are expected to be hit the hardest.

Principals of three rural schools that already struggled to meet state education standards told The Maine Monitor they expect that some students fell behind during the pandemic, potentially widening learning gaps. But all three said schools statewide are in the same boat and they won’t know the full picture until students are back at school and have taken initial assessments.

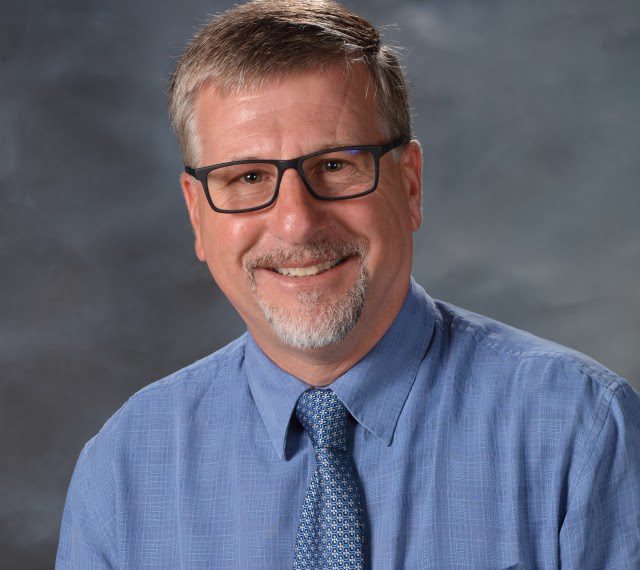

Buckfield Principal George Reuter seemed undaunted by this challenge. Indeed, the fact that Reuter’s community is small and rural may well be an asset when it comes to learning during a pandemic.

‘What comes first? Basic needs or remote learning?’

The full repercussions of the pandemic may be difficult to predict, but Catharine Biddle, associate professor of educational leadership at the University of Maine, said it almost certainly will expand existing achievement gaps. Students who already faced additional challenges like economic, food or housing insecurity had the most trouble engaging remotely and were hit the hardest when schools closed, she said.

“I do think we can say pretty confidently that the kids most disadvantaged by the pandemic are the kids who were already the most disadvantaged,” Biddle said.

Students in Buckfield, Calais and Fort Kent experience some of the challenges Biddle described, which could be tied to the problems school officials noticed with poor attendance, lack of structure and access to the internet.

And Buckfield school social worker Dana Johnson said students face other stressors during the pandemic, which prompted months of business shutdowns and caused millions to file for unemployment.

“There’s distractions. What comes first? Is it basic needs or remote learning?” she said. “I think that was a big barrier with some students. What are some stressors in the home and how are they dealing with it?”

Reuter and John Kaleta, principal of Fort Kent Community High School and Valley Rivers Middle School, said some students had additional responsibilities while learning from home, such as walking the dog or watching younger siblings. Other students had trouble accessing the internet or sharing bandwidth with other family members working from home. And some kids just “went dark” and wouldn’t communicate with teachers for days.

“When a student comes into school, they have to abide by the rules of the classroom they’re in,” Reuter said. “When that classroom extends into their home, it becomes a bit of a challenge.”

Valerie Patenaude said her Buckfield eighth grader, Chayce, attended only one video class on Zoom this spring and decided not to participate in any others. He’s shy and didn’t like talking with an audience so was reluctant to ask questions virtually, she said.

Patenaude, who is a special education technician at the elementary school, said she also disliked working from home. She held one-on-one video calls with her nine students, some of whom had poor internet connections.

Remote learning was more difficult as a parent than as an educator, Patenaude said. She had three children studying from home this spring: 13-year-old Chayce, a 16-year-old and a recently graduated senior.

When a student comes into school, they have to abide by the rules of the classroom they’re in. When that classroom extends into their home, it becomes a bit of a challenge.”

— George Reuter, principal of Buckfield Jr./Sr. High School

“I wasn’t really frustrated with my school students but as a parent I was frustrated with my own kids because you had to keep pushing them,” she said. “I had to be on them all the time to do their work. Like my eighth grader said, there’s distractions at school but there’s more distractions at home.”

Chayce said he loses focus easily and needs teachers to remind him of his tasks. That wasn’t an option when he was studying from home.

Buckfield students who didn’t have internet access got hotspots from the school, but some weren’t able to use them because they were too far from a cellular tower, Reuter said. These kids had to work offline at home, then sit in the school parking lot or another place with internet access to download homework and upload assignment work.

In Fort Kent, Kaleta said after some initial problems, all 400 students eventually had internet access thanks to offers from providers and phone companies. The larger problem was kids staying up late and missing Zoom lessons with teachers, he said. As a result, some teachers worked from 8 a.m. to 10 p.m. to accommodate students who were active at night.

“There was a high burnout for staff,” he said. This year his school will enforce specific hours for remote learning.

Mary Anne Spearin, principal of Calais Middle/High School, said some previously overachieving students also struggled with remote learning.

“Every student has different motivation levels. It really varied from student to student,” Spearin said.

Pre-pandemic, students who miss more than 10 days of school are 36 percent more likely to drop out, according to the McKinsey study. In an analysis of three coronavirus scenarios — returning to in-class instruction full-time this fall, in January 2021 or in fall 2021 — McKinsey found that dropout rates would likely increase in each circumstance.

“We estimate that an additional 2 to 9 percent of high school students could drop out as a result of the coronavirus and associated school closures — 232,000 teens (in the mildest scenario) to 1.1 million (in the worst one),” according to the study.

In the middle scenario, the average student would lose about seven months of learning, according to the study. But Black students may fall behind by 10 months, Hispanic students by nine months and low-income students by more than a year.

Patenaude said the study seemed like it was “jumping the gun” because it hasn’t been a year since the pandemic took hold.

“Just because you’re low-income doesn’t mean you’re not smart and can’t catch up,” she said. “That’s just wrong.”

Reuter didn’t seem surprised by the estimated loss of learning, but was concerned about the disproportionate impact on low-income students. About 50 percent of Buckfield students qualify for free or reduced lunch, he said.

The school’s summer meal program handed out 12 times more free meals this year than last year. Part of that increase could be because recipients were not required to eat the meals on site this year and could take home meals for multiple family members. Nonetheless, the number of free meals handed out increased from about 100 to 1,200 a week.

One major success story of the pandemic is that schools statewide were able to adjust their lunch programs, sometimes in a matter of days, to continue offering free or reduced lunches to students through the end of the school year, Biddle said.

At the other end of the learning spectrum in Maine, some upper middle-class families are pulling their children out of public school to be taught privately this fall. These students could come out of the pandemic with no learning gap, Biddle said, which moves the bar for everyone else who grappled with remote and hybrid learning models.

“That’s a level of inequity we’re OK with in this country,” she said. “Upper-class people already send their kids to private school, but we’re seeing that now at a scale that’s unprecedented.”

Meeting the challenge

Despite the challenges of remote learning, officials seemed pleasantly surprised with how many students adapted to the new environment.

Kaleta, in Fort Kent, said he expected half of his students would struggle but half would be successful when schools went remote in March. Instead, two-thirds of students did well, he said. One-third did “exceptional” while one-third had a hard time.

Students in Buckfield were able to keep up with coursework because teachers kept them busy, Patenaude said. That wasn’t the case for her nieces and nephews who live in larger towns, so she believes the results will vary between schools.

Johnson, who is entering her second year as a social worker in Buckfield, said some students really struggled, but overall “it went as well as we had wished.”

She was worried about students “falling off the grid,” so she set up virtual classrooms where she shared resources, funny videos, calming music and information about how to contact her.

“The students that I saw in the building, I felt like the connection was a little lost (in the spring),” she said. “But in remote learning, I met new students who really thrived with (it). I was meeting students I probably wouldn’t have met in the building.”

Last year, Johnson split her time between the elementary school and middle/high school, but starting this fall she will be full time with the older students. A second full-time social worker will begin with the elementary school this year.

I hope that we don’t forget the ways in which this has drawn attention to rural infrastructure challenges, both deferred maintenance on school buildings, and around HVAC systems and also around broadband.”

— Catharine Biddle, education professor at the University of Maine-Orono

The plan was in place before the pandemic because there’s been an increasing need for counseling and mental health awareness, Johnson said. Wait lists for therapists in the area can be long and other resources are far away.

Reuter said her services also will be important for students dealing with the social and emotional consequences of the pandemic and social distancing orders. Students won’t be able to see each other’s expressions or whisper with a friend when they most need support from their peers.

“When students arrive in the morning, they have a chance to see their friends and talk about what has happened in a close-knit group. Now they’re going to have to be at least three feet away with masks,” Reuter said. “A lot of that social camaraderie will be a challenge to build.”

One way teachers and administrators can prepare for the emotional toll is increasing awareness that the ways kids are acting out is tied to the stress of the pandemic, not simply misbehavior, Biddle said.

But she added that “I don’t know what more schools and teachers could be doing that they are not already doing.” Her greatest critique was that more federal relief money should have been spent on expanding broadband internet in rural areas to support remote learning.

“Optimistically, I hope that we don’t forget the ways in which this has drawn attention to rural infrastructure challenges, both deferred maintenance on school buildings, and around HVAC systems and also around broadband. That’s a hugely important investment that would have impacts beyond just learning,” she said.

Returning to the classroom

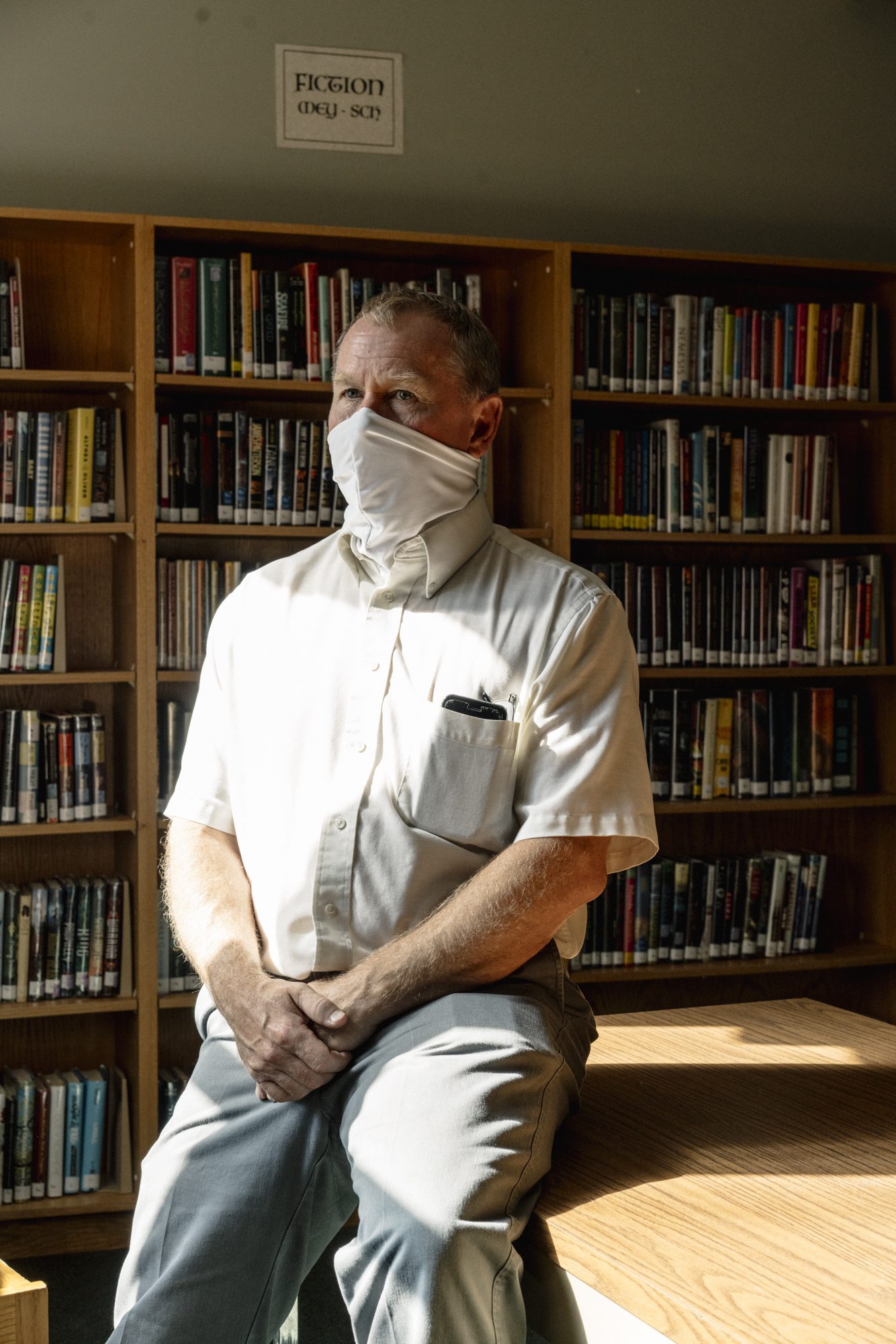

Music from the 1980s drifted down the hallways of Buckfield Jr./Sr. High as Reuter visited classrooms on a sunny August day. Students weren’t expected back for three more weeks, but already the school was buzzing. Teachers and staff were spacing out desks, powering up new laptops for students and storing new personal protective equipment.

They greeted each other through matching white masks emblazoned with the Buckfield logo. Reuter ordered the custom masks — along with gaiters and face shields — as a way to boost school pride during the strange times.

After a three-hour meeting on Aug. 10, the board for Buckfield’s school district approved a fall plan that has grades 7-12 coming back two days a week with Wednesdays remote for everyone. The elementary school will be in-person four days a week, with Wednesdays remote.

Buckfield students will begin classes Sept. 8. Valley Rivers Middle School and Fort Kent Community High School resumed classes Aug. 27 and 28 on an alternating schedule. And Calais is rotating two groups of students each day.

While it may be easier to become isolated during stay-home orders in a more remote place like Buckfield, Reuter said the strong community rallied together. The local grocery store offered curbside pickup and school resource officer Percy Turner led birthday parades for students in his 1942 police car.

High school student leaders have made videos about proper mask-wearing techniques and answered frequently asked questions. And Johnson, Buckfield’s social worker, plans to continue her community closet program that provides a collection of clothing, toiletries and school supplies for students, in line with federal health guidelines.

Patenaude said her son, Chayce, is excited to return to the school building at least a couple days a week. He will be more likely to ask questions in person, she said.

She’s not worried about returning to the classroom for her job. In fact, she’d like to have all Buckfield students back in the classroom full time.

“I think people are way more scared than they need to be,” Patenaude said. “I understand it’s a problem but I think if people are washing hands and covering coughs like they should have been doing, I don’t think it’s that big of a deal.”

Reuter said he’s received all the safety equipment he needs, such as hallway markings, personal protective equipment, hand sanitizer dispensers and even water bottle filling stations to replace drinking fountains.

The large fields around Buckfield Jr./Sr. High School offer a place for outdoor classes and regular mask breaks. Students can gather in the mornings to eat breakfast under large outdoor tents and work in the school garden as a way to get out of tightly regulated indoor spaces.

Reuter hopes the first few weeks go well so they can find a way to bring students back into the classroom more, but he’s also preparing for the possibility that circumstances worsen and they’ll have to close the school again.

“It’s just unchartered waters and everybody is apprehensive, but everybody is saying we want to do it and make it the best we can,” he said. “There isn’t a negative vibe around it. There’s a positive vibe around it to do what we can to make it the best for our kids and the community.”