It’s no secret the education field was burdened during the pandemic, with schools nationwide facing teacher workforce shortages. Now, the 2022-23 academic year is halfway done, and Maine school districts are struggling to fill the same gaps they were months ago.

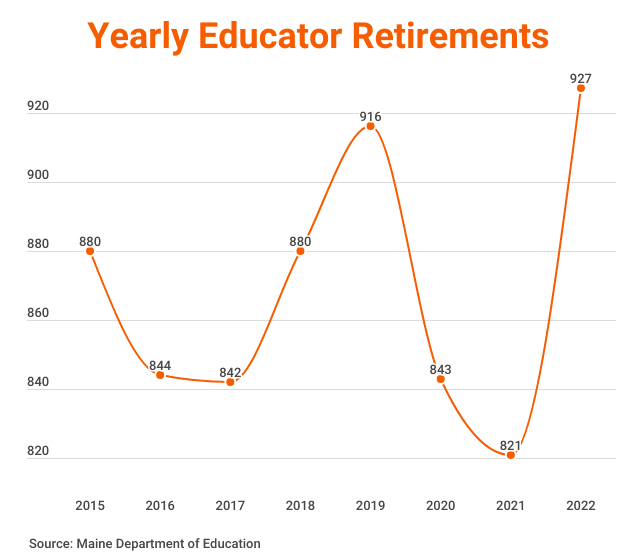

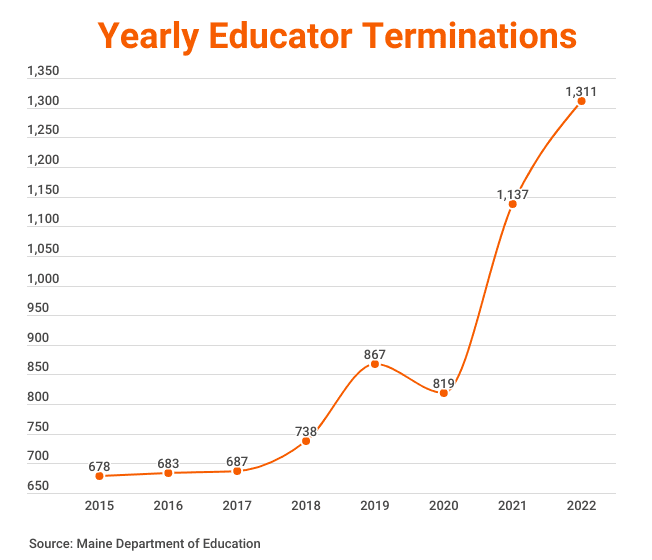

Newly released figures for 2022 show that record numbers of teachers and other educators retired or otherwise left their positions last year.

In 2022, more than 1,300 teachers, education technicians, administrators and other educators in Maine left their jobs, and more than half of them did so in June or August. The state also reported that 927 educators retired.

In both cases, the totals are the most in the past seven years. The figures are collected by the Maine Public Employee Retirement System.

But because Maine doesn’t keep track of vacant positions overall, it’s impossible to tell how many educators are needed.

This lack of tracking is something the state is trying to address through its TeachMaine Plan, said Diana Doiron of the Maine Department of Education. The group is spearheading a data project that aims to find concrete reasons behind teacher departures.

‘What’s the story?’

“It’s difficult to climb an assumption ladder and make determinations about the data when it’s data sitting in a table,” Doiron said, adding that a large goal of the data project is to find out, “what’s the story behind the numbers?”

After this, the team can start looking for solutions — but that won’t happen any time soon. Doiron said she sees the data collection process spilling into next year, at the least.

DOE Educator Excellence Coordinator Emily Doughty said the project will also provide a long-term solution to research issues.

“This plan will be something that we continue to revisit,” Doughty said. “We’re implementing strategies in a really systematic way.”

One approach that TeachMaine has already begun is creating a job board, which posts open educator opportunities through a partnership with Live and Work in Maine. Although not a comprehensive list, the DOE incentivizes its use by taking away posting fees for school administrative units.

Janet Fairman, co-director of the Maine Education Research Policy Institute, said there are three main questions that need to be answered before solutions to the teacher workforce shortage can be determined.

She agreed with the DOE that there needs to be more information about open positions, as well as more research on why teachers have left. Fairman added that another major question to answer is why high school students don’t seem to be interested in entering the profession anymore.

Right now, she said the university is seeing less undergraduate enrollment in education majors.

To understand why this might be, Fairman is working on a research project to survey undergraduate students who are studying education about why they chose their major, what their perceptions of teaching are, and what might incentivize them to teach in a rural district.

“As we learn more about what attracts people to teaching, keeps them in the profession, and what is causing them to leave, then we can start to identify where the problems are and try to form a plan to address some of those challenges,” Fairman said.

MEPRI has also noticed the increase in staff leaving their positions, Fairman added. Combining that trend with the decrease in college students majoring in education creates a “double whammy and, at the same time, a perfect storm.”

Her colleague and Co-Director of MEPRI Amy Johnson is compiling data from the DOE to see exactly who is leaving what positions. The results will not equate to vacancies or answer why people are leaving, but could shed light on where the biggest gaps in teaching are.

Rural districts see little interest

While districts hold out for solutions, they face the daunting task of filling these positions that no one seemingly wants.

In Washington County, Moosabec Superintendent Lewis Collins announced his retirement last week, but recent issues filling openings make him wonder how complicated the replacement search will get. The district has been trying for several months to fill an open third-grade teacher position, as well as three available special education roles.

“After six, seven months of advertising, we haven’t even had a phone call, let alone an applicant,” Collins said about one of the open special ed positions.

In the meantime, teachers in the district are spreading themselves thin to fill the vacancies. One teacher has been working at three different schools to keep things afloat.

“We ask the existing staff to help out, and they do so graciously, but it’s a lot of work for them, and it’s obviously not the best thing for kids not to have one regular teacher,” Collins said.

Collins added that there are a number of factors that could have led to so many openings — Moosabec’s rural location, the aging educator workforce, and personal reasons — but he thinks recruitment is the issue at hand.

“Actual interest in applying for jobs and public education has dwindled all over the state,” he said. “The landscape has altered dramatically in terms of the applicant pool.”

One reason for low turnout, he said, could be the country’s current state of mind about public education. News articles have “vilified” the system, he said, with schools getting slammed for teaching critical race theory and other issues.

Despite this, there have been recruitment efforts from Maine colleges throughout the pandemic. At the University of Southern Maine, the Maine Teacher Residency program offers students a full year of employment at a local school with an opening, while providing tuition assistance and mentoring opportunities.

This program launched during the pandemic as a means of alleviating the stress of the teacher workforce shortage. USM supports students through a one-year internship residency.

The model, which is used nationwide, is meant to support those who could not afford to study without work, said University of Southern Maine professor of education Flynn Ross.

However, there’s a fine line between accessibility of programs, Ross said, and over-incentivization. She added that during the pandemic, some policies changed to open doors to all, which backfires.

“That creates a revolving door,” Ross said. “People come in, they can’t do the job. Well? They burn out, they leave.”

She also pointed to teacher salary as one of the main catalysts for those leaving the profession, and as a deterrent for those coming in.

“The places that are hardest to teach and with lowest teacher salaries have the greatest teacher turnover,” Ross said.

Fixing this issue, she said, is about more than investing in teacher salaries, though. It will require money to funnel back into education, through programs like USM’s residency service. She said it will also require new policies, including the bill that state Sen. Teresa Pierce (D-Cumberland) is drafting that would introduce new solutions, including more residency programs.

“Nations that invest in their teacher quality get the best results,” Ross said.