Editor’s Note: The following story first appeared in The Maine Monitor’s free environmental newsletter, Climate Monitor, that is delivered to inboxes for every Friday morning. Sign up for the free newsletter to get important environmental news by registering at this link.

Within the past week, the National Weather Service station in Caribou has posted videos on Twitter of heavy snow piling high in their office parking lot, and that same snow dripping off their roof under bright, springy sun.

Down here in Portland, we got a nice overnight dusting of snow earlier in the week, but it didn’t last long. I’ve listened to the snow drip away as temperatures climbed into the 50s — uncanny, record-setting territory for Feb. 16, on the eve another forecasted snowstorm and cold front coming Friday and this weekend.

Maine is again experiencing pronounced “winter whiplash,” as some scientists call it — ricocheting from cold, snow and ice to record-breaking warmth, rain and melting, and back again. Overall, this has been the second-warmest period from Nov. 1 to Feb. 13 on record in Portland. Nine out of the top 10 years on this list have occurred since 2000, according to the NWS in Gray.

Researching for this newsletter, I found an article I wrote for Spectrum News Maine on this exact same topic, almost exactly one year ago. Highs in the 60s in late February 2022? I barely remember. It’s starting to feel like the norm.

“I like a warm spring day just as much as anybody else, don’t get me wrong, but it feels strange when that warm spring day that feels like May happens in February,” University of New Hampshire climate researcher Alix Contosta told me for that story. “It just makes me feel like I’m out of sync with reality. It’s sort of like waking up in the middle of the night and seeing that the sun is shining in the sky — just something doesn’t feel right about it.”

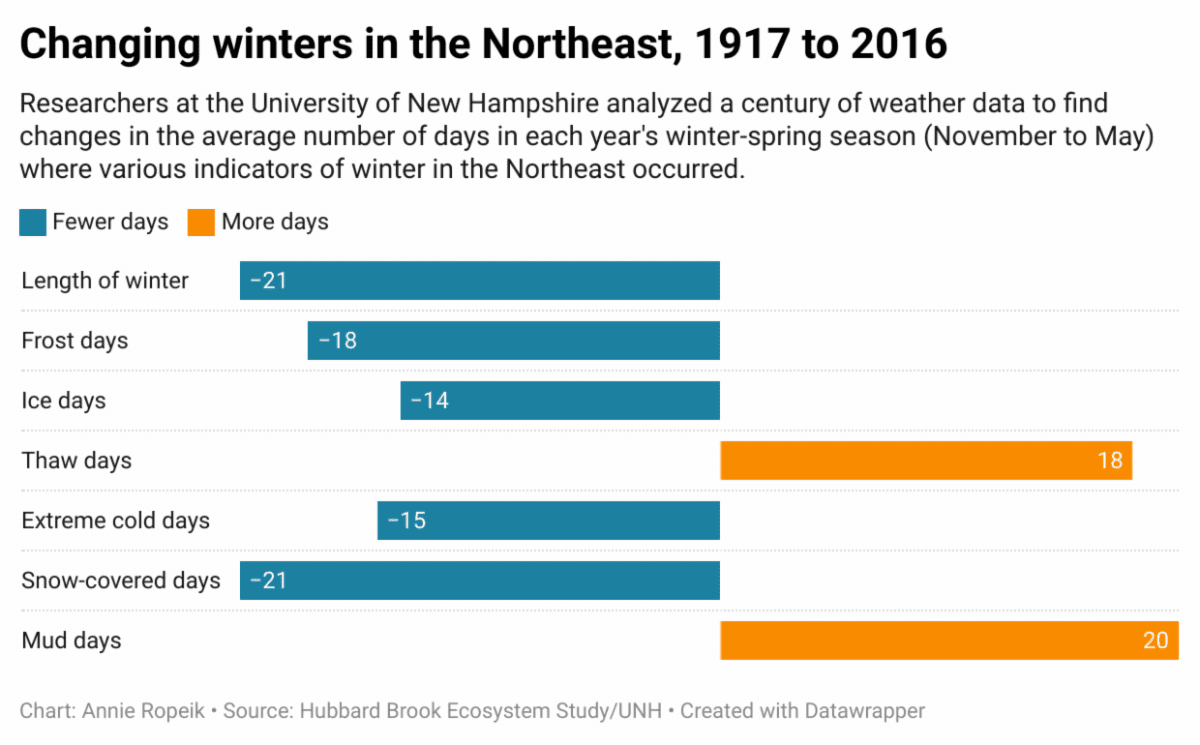

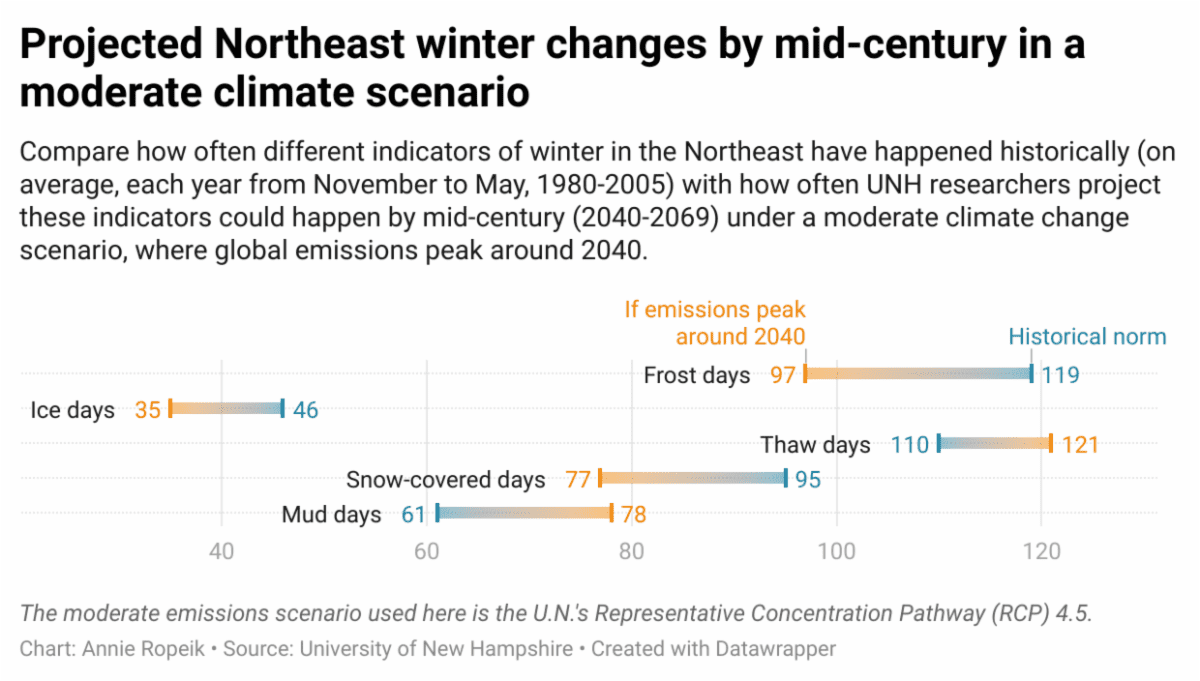

Contosta (we also heard from her when I wrote about unusual warmth Maine experienced last fall) and her colleagues at UNH and elsewhere have spent years researching what climate change is doing, and will do, to winters in the Northeast. They’re especially interested in changing snow patterns, and the myriad effects of this change on soil, water, plants, animals and humans.

Take the rapid snowmelts we’ve experienced frequently so far in this mild winter in Maine. Persistent snow cover keeps the ground protected from temperature swings and erosion, helping it hold onto carbon and nutrients.

“When mud days [bare ground with temperatures above freezing] occur before forest canopy leaf out… they may result in wetter soils,” the UNH researchers wrote in a 2022 paper. “A warmer, moister period between winter and the growing season may result in greater ecosystem carbon and nutrient losses.”

That released carbon contributes to warming, which contributes to weakening winters, compounding the problem. We see this too in how warming ocean waters are less effective at storing carbon. It’s a vicious cycle. Snow cover reflects much more light than other natural surfaces, creating a cooling effect — so less snow means less cooling, warmer air, less snow … on and on.

Snow also provides habitat and hunting ground for many Northern critters. Some can forage and roam in snow, but not in ice — which can form more often as snow melts and refreezes, or when rain falls on top of snow and solidifies. Federal research says this poses an increasing problem for Arctic indigenous communities that rely on these ecosystems for food.

A 2022 study from the University of Nebraska found rain was most common as a cause of snow loss in the northeast and northwest parts of the country. And a 2016 Climate Central analysis found that more than half of weather stations in Maine have seen more winter rain since around 1950.

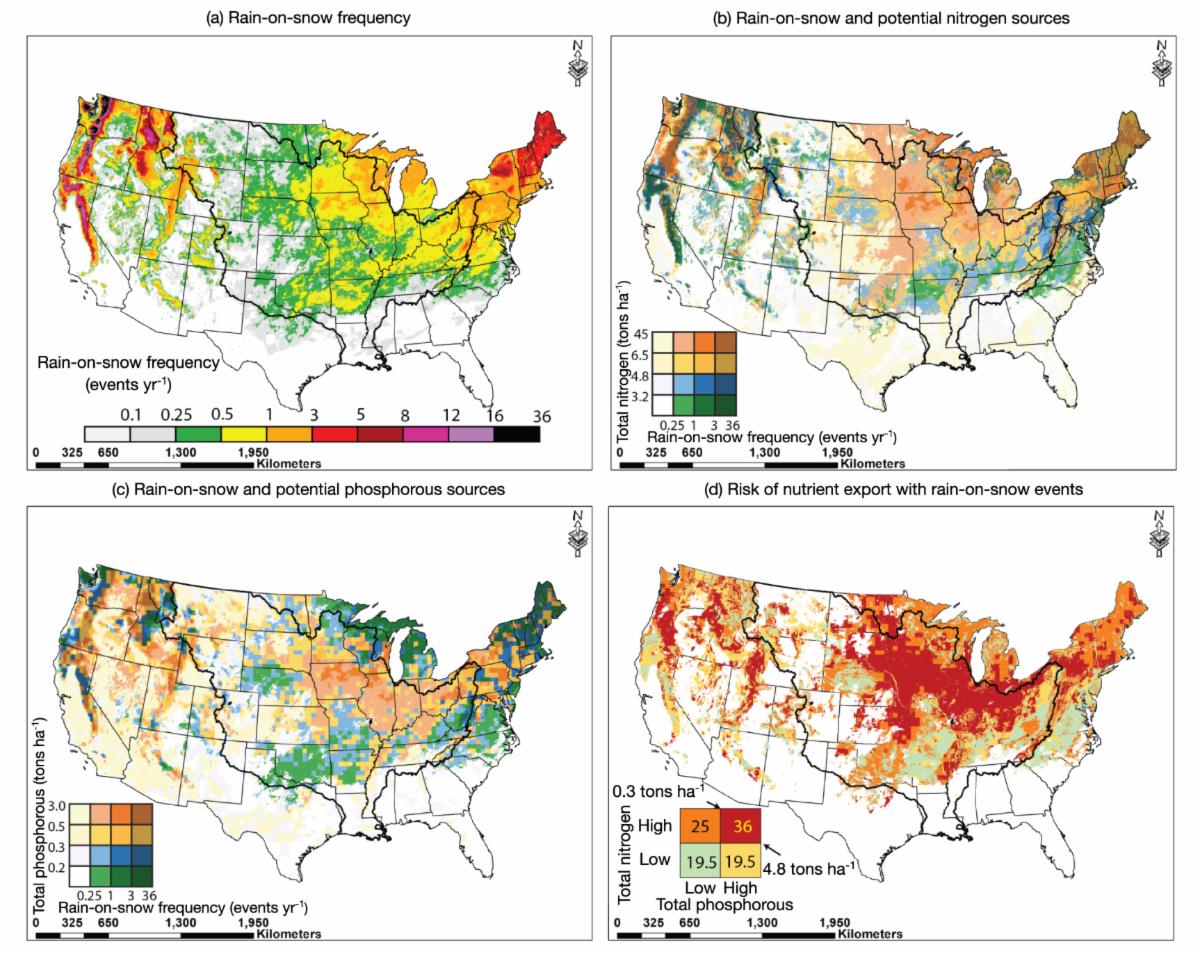

Nutrients released from soil beneath melting snow have harmful effects, too — substances like nitrogen and phosphorus, which fertilize plants in soil but can degrade aquatic ecosystems if they build up. The low-oxygen “dead zone” in the Gulf of Mexico, fed by upstream agricultural runoff, is a prime example of this.

A recent study from the University of Vermont shows Northern New England as a hotspot for combined nitrogen concentrations and rain-on-snow events, which are primary drivers of runoff. We covered this last fall at a journalism collaborative where I also work, the Mississippi River Basin Ag & Water Desk.

“Winter events tend to carry a little bit more pollution than the same size event in the growing season,” researcher Carol Adair told KCUR reporter Eva Tesfaye. “That’s largely because there are no plants around taking things up.”

In places like Maine, we rely on snow for so many “ecosystem services” — these unseen ways our environments protect us and make life as we know it possible.

Snow holds onto water that can be released to replenish ground- and drinking water supplies in spring thaws. If it melts too early or often on frozen or dormant ground, it can’t provide that benefit, which could drive short-term summer droughts. Winter whiplash can also cause ice jams or floods.

The New England winters we used to know past are key to snowmaking for skiing, ice for ice fishing and more. And cold weather helps control summer populations of invasive pests and disease-carrying ticks and mosquitoes.

“The loss of cold and snow in northeastern North America will continue or accelerate, particularly in the southerly and coastal areas of the region, which could see near-total loss of snow and freezing temperatures,” the 2022 UNH paper concluded. “These changes portend possible reorganization of social and ecological systems that have historically relied on cold, snowy winters for habitat, water resources, forest health, local economies, cultural practices, and human wellbeing.”

And the less humans are able to curb greenhouse gas emissions, the scientists added, the more cold days and snow cover the region will stand to lose.

To read the full edition of this newsletter, see Climate Monitor: As winters warm, it’s never too early for mud season.

Reach Annie Ropeik with story ideas at: moc.l1760779667iamg@1760779667kiepo1760779667ra1760779667.