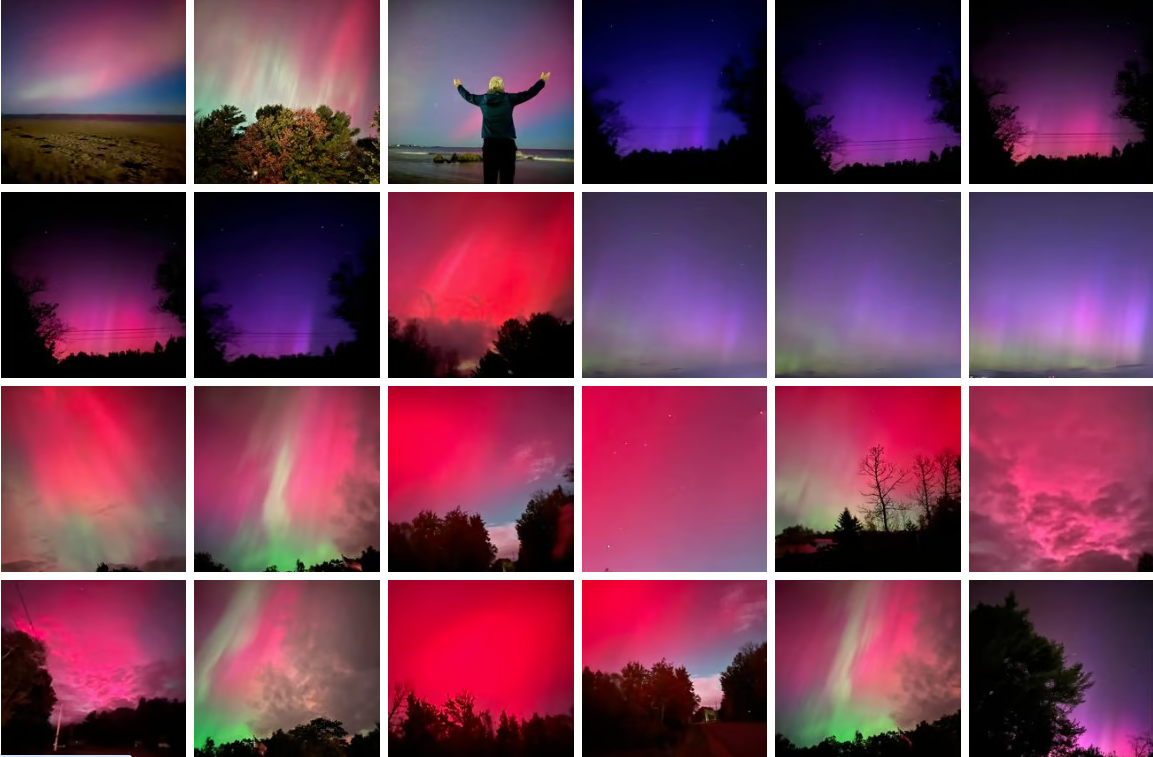

Good morning from Mount Desert Island, where the aurora borealis showed up in absolutely spectacular fashion last night.

I’ve seen the northern lights just once before, dancing green outside the window of a plane over the Atlantic Ocean. I always imagined that seeing them again would require a long journey to the Norwegian tundra or some other such wild and hard-to-reach place.

Instead, all I had to do was step out of my front door last night around 7:30 p.m. and look up. The lights appeared first to the west as a soft, diffuse band of green before moving into pink and red in the sky to the northeast.

They didn’t “dance” in the way they do in timelapse photos, nor do they appear as brilliant to the naked eye. But it was magical nonetheless, one of those rare otherworldly phenomena that bring people pouring into the streets, collectively, if momentarily, awestruck by the majesty of our planet.

The online message boards about space weather read like a sci-fi novel from the 70s, with enthusiastic discussions about the plasmasphere and sunspots and magnetic flux. Space weather is exactly what it sounds like — weather in space — as opposed to terrestrial weather, the weather we feel at the surface of the earth.

Both begin with the sun, which is less a “mild and beneficent force” and “bestower of good moods and great tans,” as journalist Kathryn Schulz put it, than it is “an enormous thermonuclear bomb that has been exploding continuously for four and a half billion years.”

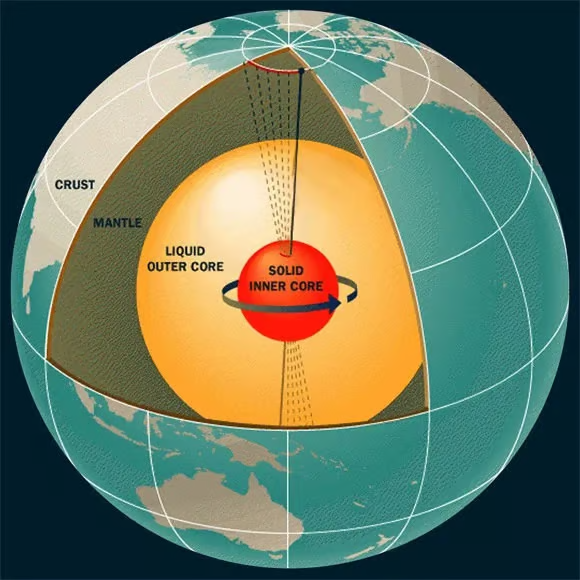

Both the Earth and the sun have magnetic fields. Ours originates from fluid in our planet’s outer core, just below the mantle, as the molten metals there churn and roil, generating electrical currents hundreds of miles wide.

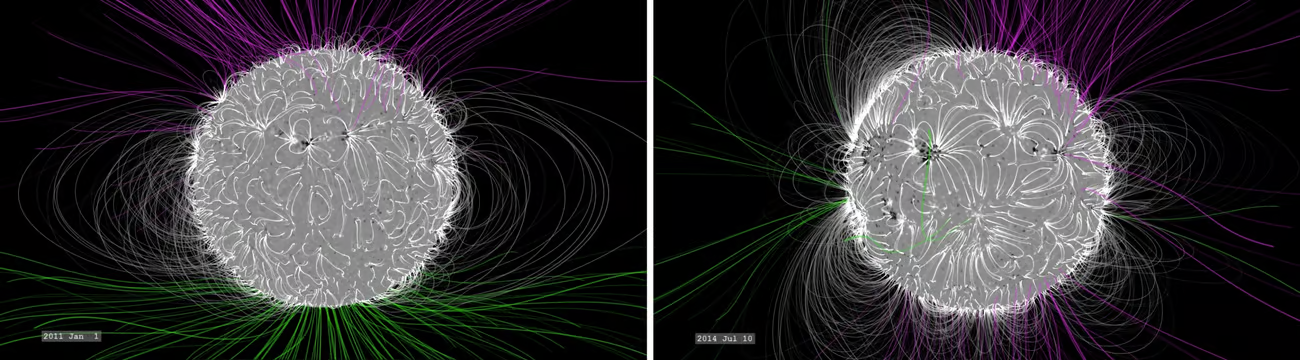

Scientists aren’t entirely certain where on the sun its magnetic field originates, but they do know that it is massive (far larger than Earth’s) and drives a roughly 11-year activity cycle, growing slowly more tangled and disorderly (solar maximum) before smoothing out and reaching its simplest state (solar minimum).

The sun is largely composed of plasma, that supercharged, soupy fourth state of matter created by heating a gas to the point that its electrons break free from their atoms. We can observe the shape of the magnetic fields above the sun’s surface because they guide the motion of that plasma into loops and towers in the corona, the sun’s outermost atmospheric layer.

At solar maximum the sun’s magnetic field is messy, and conditions are ripe for solar explosions, like solar flares (bursts of radiation) and coronal mass ejections, billion-ton bubbles of plasma that erupt from the sun’s surface and hurtle toward Earth at incomprehensible speeds.

The most recent coronal mass ejection, which exploded Tuesday evening, was moving at roughly 2.5 million miles per hour.

Solar wind (which is not so much a wind in the conventional sense as it is charged particles constantly spewn out by the sun) brings these particles to Earth, temporarily cracking our geomagentic shield and allowing some of the sun’s energy to penetrate. As you may recall from high school physics, moving a magnetic field around creates an electric current. This disruption in Earth’s magnetic field is known as a geomagnetic storm.

The aurora is one of the manifestations of geomagnetic storms. These storms are classified by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration on a “G” scale of 1 to 5, with G1 being minor and G5 being extreme.

The scale is partly based on an index called the Planetary K index, or Kp, which measures a range of currents and magnetic deviations in Earth’s magnetic field. Disturbances with a higher Kp index (between 7 and 9) produce bright auroras that are visible at lower latitudes; a moderate Kp of 5 or 6 will generate an aurora that is less bright and visible closer to the poles.

The colors we see are the result of the collision of particles from the sun with gases in the Earth’s atmosphere, and they differ depending on which gases the particles are colliding with and how much energy is exchanged.

This week’s geomagnetic storm will likely be smaller than the one in May, said Shawn Dahl of the Space Weather Prediction Center in a briefing with reporters earlier this week. The storm in May, Dahl explained, was the result of a series of coronal mass ejections, which “enhanced the effect.”

Tuesday’s coronal mass ejection was much faster than those in May but was a singular ejection, rather than a series. Scientists aren’t sure how long the cloud will wash over us, said Dahl, but expect the G4 conditions to last for about 36 hours. Don’t despair if you missed it — you’ll have another chance, perhaps tonight (keep an eye on the forecast) or later this year.

“We’re still in for a ride with this solar cycle activity,” said Dahl, possibly into early 2026.