Rhonda McIver screamed their names as she searched the sky and the forest.

“William! Kelly!” she hollered.

“I look for a sign from them,” McIver explained. “I’d do anything to bring them both back.”

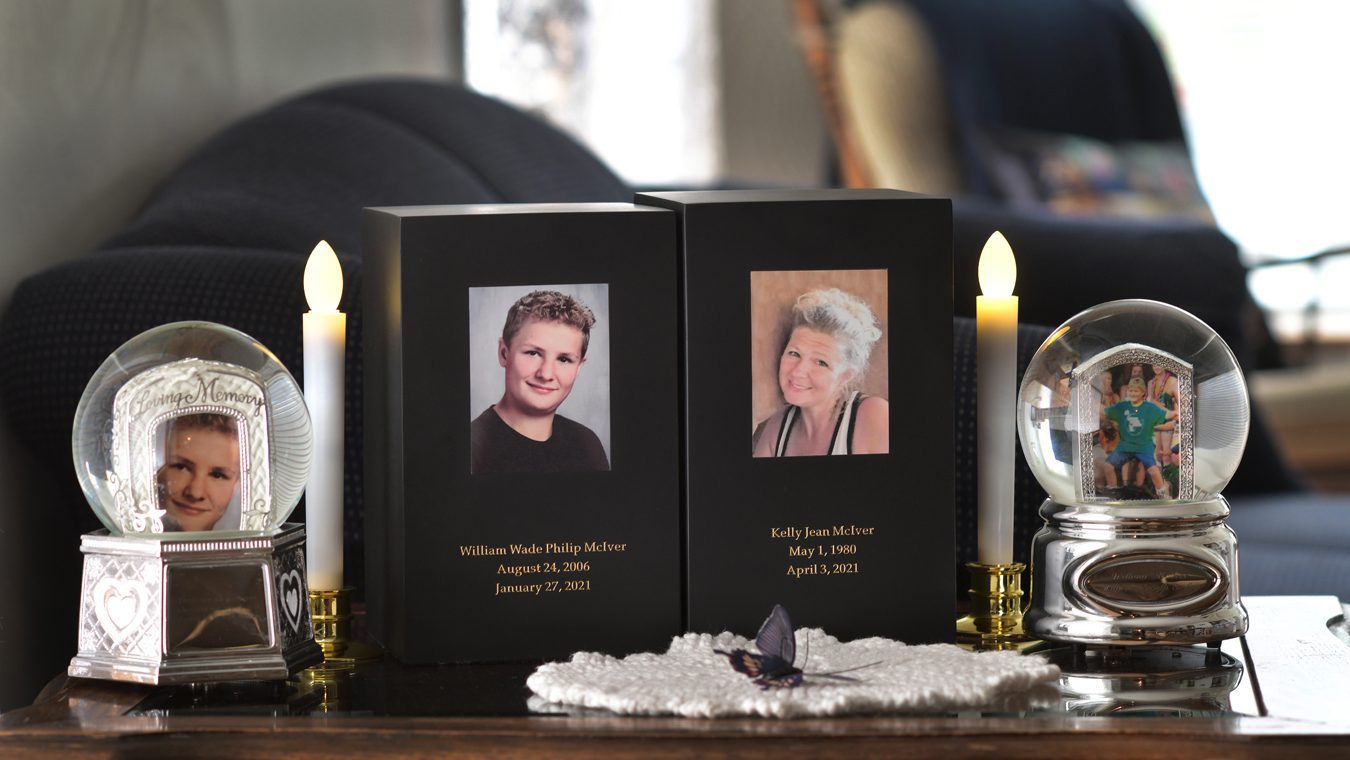

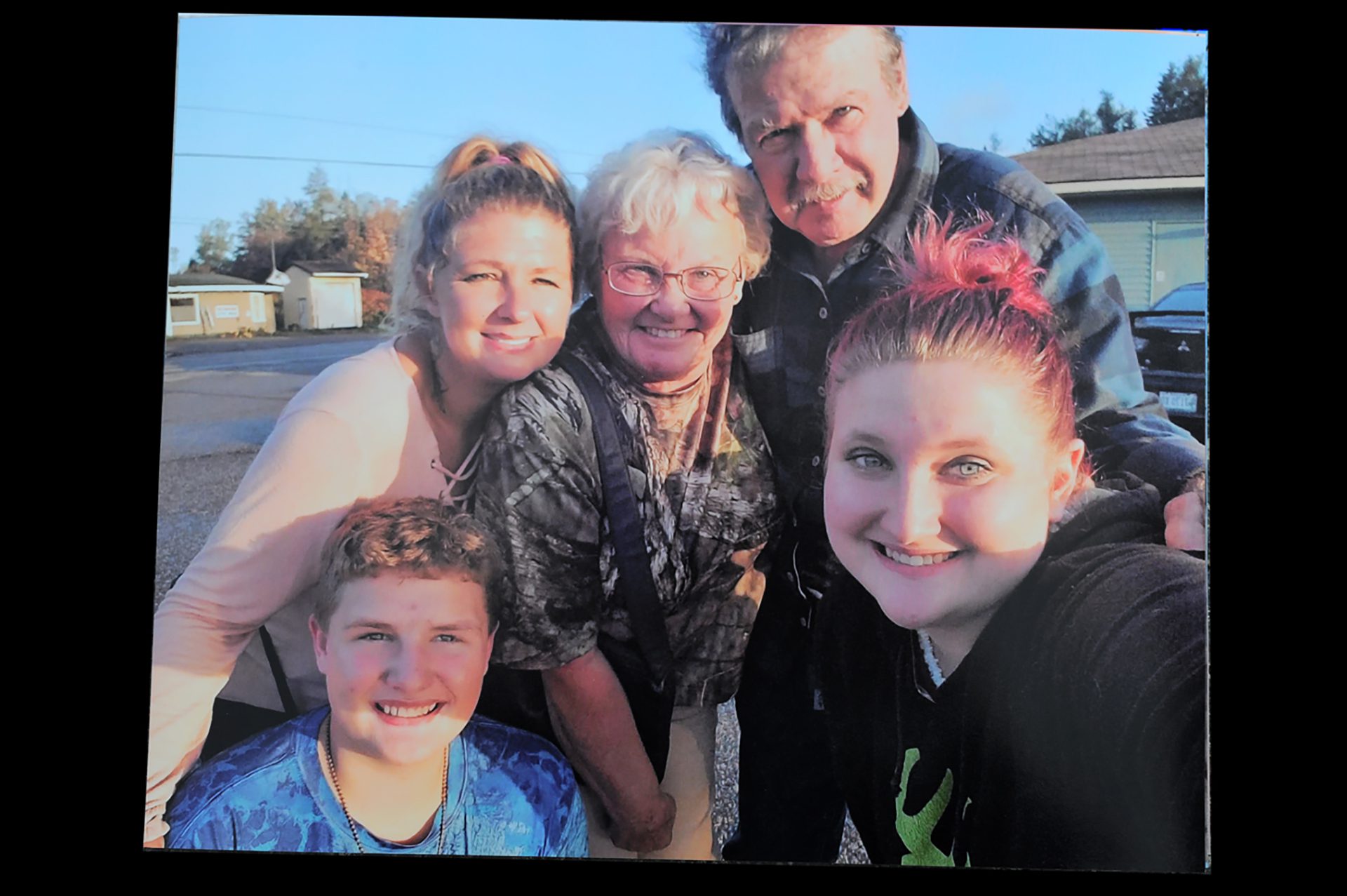

McIver lost her grandson and daughter over a nine-week stretch. Her 14-year-old grandson William killed himself on Jan. 27. Her 40-year-old daughter Kelly – William’s mother – overdosed on April 3.

“I scream their names every morning when I walk,” McIver said. “I scream as loud as I can.”

McIver lives in Baileyville, a small town in the northeastern reaches of Washington County. Here in this remote stretch of communities, loss and despair have shattered many families during a heartbreaking pandemic winter.

Three young men and William McIver ended their lives between December and January.

Drug overdoses doubled from 10 in 2019 to 20 in 2020 in a county with less than 32,000 people, according to the attorney general’s office.

“People keep losing and losing,” said Bonnie Stewart, whose 28-year-old son Daniel killed himself Dec. 8 near his Pleasant Lake home. “You hear about another suicide, another overdose. How much can one family, one community take?”

Pandemic isolation, job losses and surging depression added to Washington County’s woes, where poverty and unemployment are often the highest in the state.

“We had people barely hanging on before COVID hit,” said Shannon Small, a former Washington County drug and alcohol counselor. “Then when everything shut down, people lost their counseling and substance abuse programs. It was easy to fall back into bad habits.”

Before the pandemic, treatment for depression, anxiety and substance abuse was difficult to find, Small said, and now waiting lists have grown longer.

“We live in an area that is so deprived of resources as it is,” said Small. “Every place that is trying to help is so overstaffed and overwhelmed.”

Small herself is overwhelmed on how to help her close friend Rhonda McIver.

“It’s hard to wrap your mind around it,” Small said. “I can’t imagine burying two children in two months.”

• • • •

Kelly Jean McIver loved horses.

Her affection was fostered by her mother, who owned and boarded horses at her home. McIver taught her daughter how to ride when she was young, and though Kelly lost interest in her teens, later in life horses “would become her saving grace,” McIver said.

Kind-hearted and sensitive, Kelly had plenty of friends, but she struggled with self-confidence and addiction, McIver said.

McIver worried about the daughter she and her husband adopted as a 9-day-old baby. Not long after graduating from Woodland Junior-Senior High School, Kelly enlisted in the army, where she suffered a shoulder injury.

“She had operations and started taking pills for the pain,” McIver said. “I think that’s where the trouble started.”

Later in life as she started her own family, Kelly and her husband tried to wean off opiates with counseling and methadone. But her husband never fully recovered, McIver said. He died of a heart attack in his sleep. At age 28, Kelly became a widow.

“Kelly fell apart,” McIver remembered. “We took William in then. He was 2 when we adopted him.”

For the next several years, Kelly battled substance use, McIver said, and was ashamed of her addiction.

“Kelly always said, ‘Mom, I don’t want to be a drug addict.’ ”

At times during her turbulent life, Kelly lived with her parents and cherished moments with her son.

“She and William had so much fun together,” McIver said. “They’d ride dirt bikes and sing country songs. They both had sparkle in their eyes.”

As she fought to stay sober, Kelly found solace in riding Stitch, the quarter horse gelding her mother bought her. She spent hours riding with friends and family along Washington County’s quiet logging roads.

“Horses were so therapeutic for her,” said Marie Paul, Kelly’s friend. “She really felt loved by Stitch.”

Kelly was also a popular instructor, teaching children to ride. In the summer of 2019, she opened her own business: Farrier Shoes by Kelly.

“It made her feel proud of herself,” McIver said.

Before the pandemic arrived, Kelly enrolled in a medication-assisted treatment program. She received counseling and took Suboxone to help ease her cravings for opiates. Her farrier business began to grow, and she moved into an apartment in Baileyville. She also started seeing an old boyfriend.

“She started slipping then, drinking and doing drugs with him,” McIver said.

As the pandemic continued into the winter, Kelly’s son William struggled, too. The 14-year-old boy had tried to end his life the year before and received counseling.

Like his mother, William battled depression and anxiety, which he had trouble talking about. On the morning of Jan. 27, McIver found her grandson in his room. The boy had killed himself during the night.

“I don’t know why he did it,” McIver said. “That’s the hard part. He was so good at hiding his feelings. He was always trying to make everyone else happy.”

Rhonda and Kelly tried to comfort one another as they grieved, but Kelly slipped further into depression and drug use.

“She really plummeted very fast after William’s death,” said Marie Paul, who attended recovery groups with Kelly. “She quit her groups, her program. She was supposed to be going to rehab, but everything just stopped.”

Three days after her son’s death, Kelly shared her emotions on Facebook.

“I can’t even wrap my head around the fact he isn’t coming back. I would give anything to have him see how loved he was by so many. … He could always make me laugh no matter how bad I felt. I wish I was able to do the same for him that night.”

Kelly urged anyone who was depressed or suicidal to reach out for help.

“If any of you are feeling like things are that bad and nobody will care if you’re gone, think of William and know that you are wrong and reach out to someone. Anyone. I will help anyone who is at that point in any way I possibly can. Anytime day or night.”

In late February, Kelly posted a video on Facebook that included several pictures of her son. The photos captured William grinning as he fished, swam and sat on his four-wheeler.

“I can’t believe it’s been a month since I saw that smiling face. Or got a phone call to tell me some hilariously stupid joke. … My heart is so very broken.”

Despite her anguish, Kelly sought to ease her mother’s pain and burdens. She helped care for her father, Larry who has dementia, and worked in the barn cleaning stalls and feeding the horses.

“I’d go over to Kelly’s apartment every morning about 7:30 for coffee,” McIver said. “She was my rock.”

On April 1, Kelly shared a Facebook post about the April Fool’s Day pranks that she and William had orchestrated. They reveled in elaborate hoaxes, Saran-wrapping McIver’s entire jeep, her computer and the kitchen table.

“This was our favorite holiday,” Kelly said on Facebook. “It was OUR day. We would spend months planning and sooo much money. … This will be the worst day of the year for me for probably the rest of my life.”

On April 2, at 2:39 a.m., Kelly texted her mother that she had broken up with her boyfriend.

“It was a bad night,” she said.

McIver saw her daughter later that day. Kelly talked about going back into a recovery program.

“She had plans to go to a rehab,” McIver said.

The next morning, McIver phoned her daughter several times. When her calls went unanswered, she drove to Kelly’s apartment. Just after noon, she found her daughter dead from an overdose.

Baileyville Police Chief Bob Fitzsimmons arrived at Kelly’s apartment soon after learning about her death. Fitzsimmons had known Kelly since she was 18. He tried to get her into recovery programs and worried about her, especially after her son William’s suicide.

Fitzsimmons found fentanyl and crack cocaine in Kelly’s bathroom. A hypodermic needle and a plate of food lay next to her in bed. During his investigation, he learned that Kelly had overdosed three times the week before and had been revived with naloxone.

Later that day, Fitzsimmons held Rhonda McIver’s hand as the 69-year-old woman sobbed.

“I feel like I let her down,” Fitzsimmons said. “It’s always the question, Why? What could I have done differently to prevent this?”

The tragic deaths during the past few months have weighed on Fitzsimmons. He grew up in Baileyville and knows most of the people in the small town of 1,500. He was still torn up over losing William McIver when he was called to Kelly’s apartment.

“It’s been the toughest year of my career,” Fitzsimmons said. “I’m just trying to hold people together.”

Over two decades of policing, Fitzsimmons has kept track of the people he lost to murders, accidents, suicides and overdoses.

“I try to coax their stories from their last hours on earth,” Fitzsimmons said. “William was my 47th loss. His mother Kelly was the 48th.”

Now, Fitzsimmons worries about Rhonda McIver. The chief has checked on her nearly every day since William’s death. He sometimes messages McIver at 3 a.m. when the two of them struggle to sleep.

A few days before Kelly’s May 1 birthday, Fitzsimmons learned that McIver had a terrible night. She had taken her husband to the hospital after one of his frequent falls. Exhausted and heartbroken, McIver told a friend she didn’t want to live anymore and was having suicidal thoughts.

Minutes after she hung up with her friend, a Baileyville police officer arrived at McIver’s home to talk with her and make sure she was OK. The next morning, Fitzsimmons stopped by.

“I’ve already lost two people in this family,” Fitzsimmons told McIver. “If you went ahead and did something to yourself, I don’t know that I could go on with this job. I can’t lose an entire family.”

Fitzsimmons talked with McIver about getting counseling, and help to care for her husband. He also suggested they dedicate one of Baileyville’s four-wheeling trails in William’s name.

“I won’t do this without you,” the chief told her. “So you’ve got to stay with me.”

The suggestion to honor her grandson pulled McIver back from her dark thoughts.

“He threw me a lifeline,” McIver said.

For much of her life McIver has taken care of herself and her family; admitting she was in crisis was difficult.

“It makes you feel weak and selfish,” she explained. “I can see why people quietly give up. When people are crying for help, you’ve got to take them seriously.”

Before Fitzsimmons left McIver’s home on that spring morning, he took a plaque that McIver made in memory of William. The chief brought the memorial to Woodland Junior-Senior High School, where the boy was a freshman. In the center of the plaque, there is a picture of William grinning as he stood by his mud-spattered four-wheeler. Beneath the photo, etched words read: William W. P. McIver 8/24/06 – 1/27/21. A special fun-loving young man gone too soon. Please everyone be kind. You never know what someone is going through. Rest in Peace. Forever in our hearts.

It has been nearly four months since William killed himself and six weeks since Kelly overdosed. Most days are still a struggle for McIver. Phone calls, visits, cards and homemade meals from family and friends are a blessing, she said.

“But some days,” McIver added, “I am hanging by a string.”

Awake in the early-morning hours, McIver forces herself from bed as the sun rises. Most days she heads out to walk her dog before her chores begin. Eager for hope, she scans the sky and woods, searching for signs from her daughter and grandson.

A few days after Kelly’s birthday, McIver saw a bright light shining through the trees. It looked like a beacon on the horizon.

“It was the sun, but I’d never seen such a strange light before,” McIver said. “I’ve got to believe they were trying to let me know they were OK.”