Jon Loring’s neighbors were afraid of him.

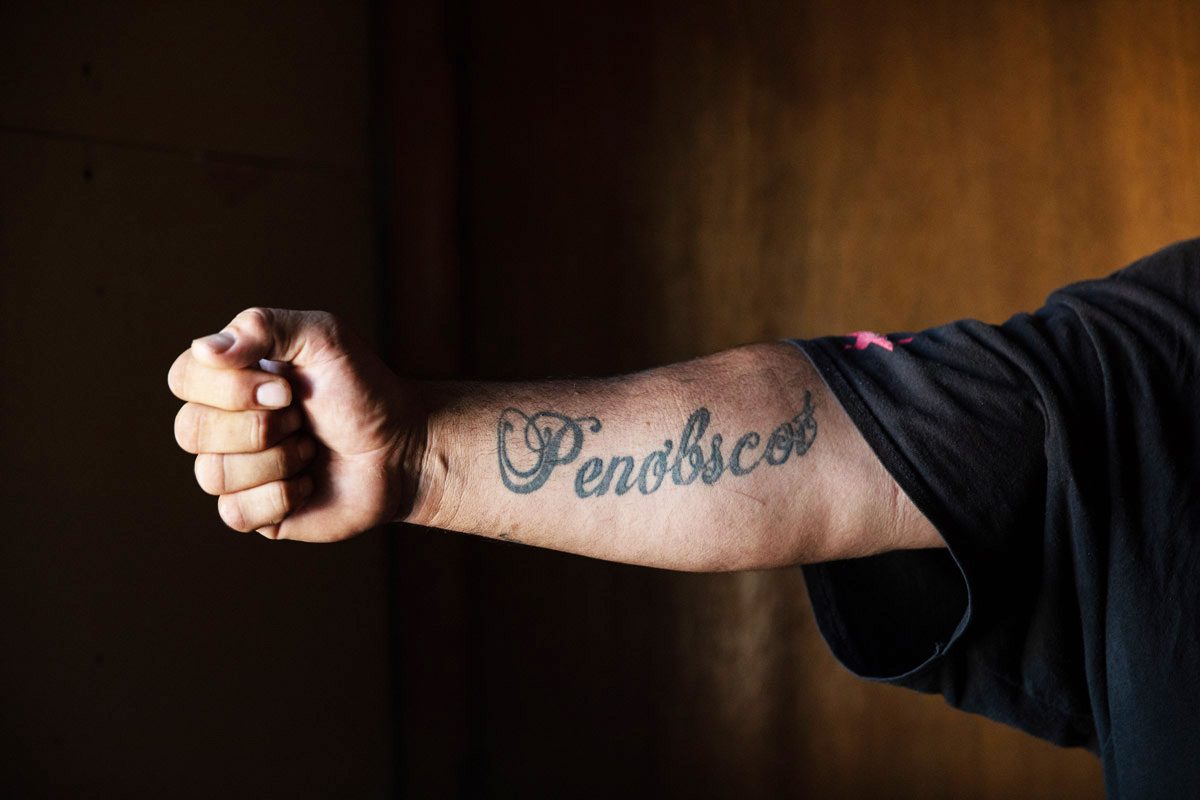

A burly man with a history of legal trouble, Loring had been using drugs for more than two decades – pot then pills and on to cocaine and heroin – when, in August 2016, drug enforcement officials in hazmat suits seized the steep-roofed house on the Penobscot Nation reservation where he had been cooking methamphetamine.

He went on the run before he was arrested last year and convicted of operating a meth lab. As his jail term was ending, Loring asked to be admitted to the Penobscot Healing to Wellness Court, the tribe’s intensive and culturally sensitive drug court. The court’s decisions primarily are made by consensus among a team of community leaders. They said no.

Loring persisted. The father of six, then 41, wrote in a letter to the court last September that he’d thought long and hard about his life choices and was “deeply sorry for the impact to my children and the future generation of our people.”

The Penobscot drug court shares many of the basic functions of Maine’s six Adult Drug Treatment Courts, started in 2001 to direct people with substance-use disorders from a punitive judicial system into a court-run program aimed at fostering recovery and reducing the rate at which participants reoffend. Like the state drug courts, the Penobscot program provides intensive case management and counseling for a year or more, frequent drug testing, and a balance of sanctions and incentives.

In other ways, the tribe’s court is markedly different.

Each of its sessions starts with a prayer and a smudging – burning sage and other traditional medicines are carried from person to person, and the smoke washing over them is meant to cleanse and ground them at the start of a ceremony. Participants also are expected to attend regular drumming circles, language classes or other Penobscot cultural events. And, perhaps most importantly, the sentiment expressed in Loring’s letter – that what happened to him would set the path of generations of tribal members to come – is a central tenet of a program that is focused as much on community healing as it is on individual recovery.

At a time when scholars are calling for the U.S. judicial system to be more responsive to cultural differences, the Penobscot court has become a model for restorative justice in a tribal context. Court leaders have been asked to share their strategies at national conferences. They serve as formal mentors to tribes developing their own programs. And Loring, who ultimately was admitted to the drug court under a cloud of doubt, has become one of its best ambassadors.

For starters, he persuaded his brother to join the program. Kris Loring, 39, also was arrested for running a meth lab in reservation housing, one his brother had started. Both men ultimately were released on probation on the condition that they complete the drug court program. It meant returning to a place where people were deeply wary of them.

While Maine’s state drug courts hear cases from across a whole county, Penobscot Nation’s serves a small, clearly defined community. The tribal nation has 2,399 members, about 430 of whom live on Indian Island.

Having the court located directly in the community means that island residents often see the brothers coming and going from the court offices, housed in the old parish hall of historic St. Anne’s Church, just off the bridge that connects Indian Island to Old Town. They’ve interacted with them at community events. They’re seeing them change.

Kris Loring, who lives in Bangor, had been a firefighter with the tribe, so his meth lab arrest surprised many who knew him in that role. “They slowly let you back in,” he said. “You can tell they really don’t trust you fully, I guess you could say, but they trust you more than they did, that’s for sure.”

Incorporating traditional practices enhances the program

When the latest iteration of the Penobscot Healing to Wellness Court launched in 2008 with longtime civil rights attorney Eric Mehnert as judge, it looked much like a traditional drug court. Attorneys sat at tables facing the judge’s bench. As in the state courts, participants worked their way through four phases, starting with more intensive monitoring and ending in a phase that emphasizes planning for the future.

Three years later, Rhonda Decontie was hired as clerk and eventually began suggesting changes based on her experience as a girl tagging along with her Algonquin father, a substance-use counselor who incorporated traditional practices with his professional ones.

At that time, program participants often were referred to speak to a tribal elder, but Decontie knew it would be difficult for people newly in recovery to seek out that help for themselves. She suggested getting help from the tribe’s cultural preservation office, and eventually the court began organizing events that could bring the community together more naturally, including a monthly sweat lodge ceremony, a group ritual involving prayer and a traditional steam bath.

Decontie suggested naming phases 1 through 4 for traditional medicines – tobacco, cedar, sage and sweetgrass – and presenting participants with those medicines as they advance in the program. And what if the court removed tables, she offered, and invited people to sit in a circle, with everyone given a chance to speak?

Mehnert and case manager Brianna Tipping credit Decontie, now a cultural advisor to the court, for changing the nature of the program. Today, she also volunteers to drive participants to evening recovery meetings and sews regalia – ribbon shirts for men, shawls or skirts for women – for program graduates.

“This isn’t rocket science,” Decontie said. “I didn’t create this. I just implanted it into a program that needed it … I’m just a message carrier.”

With support from the recovery program, Jon Loring reached out last year to Tim Shay, a spiritual leader. It wasn’t an easy call for him. Shay had been Loring’s next-door neighbor before the arrest. He had witnessed Loring walk away from his home after investigators seized it.

Loring’s legal history included stints in state prison for robbery and in the county jail for burglary and assault. Shay said he knew that people in the community wanted to see Loring locked up.

But Shay also recognized something in Loring.

“I just realized, you know, it’s a soul sickness,” Shay said. “I understood it.”

He invited Loring to attend peyote ceremonies, where participants gather to drum and sing through the night while ingesting peyote cactus, a hallucinogen and a sacred medicine. Loring began helping Shay, a sculptor, in his studio. Shay encouraged Loring, who is unemployed, to explore his creative skills as a means of supporting himself and of connecting to his own family legacy. Frank Loring, Kris and Jon’s grandfather, was a longtime game warden for the tribe and an accomplished carver.

“You take something away from somebody who has been dependent on it for so long, you have to replace it with something,” Shay said.

Toward that end, Jon Loring spent about 80 hours this summer making a ceremonial eagle feather fan. Drug counselor Dale Lolar had given Loring the feathers after Loring told him he was feeling worried he could slip up and use drugs again.

Focusing on the fan – taking it apart and remaking it again and again until it was just right – shifted his focus, Loring said: “Medicine talks to you.”

For Kris Loring, whose two children live in Milford and who picks up work when possible as a landscaper, the spiritual component of the court has been less central. But he said the relationships that he has built are profound.

He has long loved to canoe. When he was using, his canoe became a place to do drugs. Now, he said, it’s one thing that helps keep him sober. Before his recent move to Bangor, he paddled almost every day, putting in at a spot near the Milford apartment he shared with his brother, with the court building visible just across the river. In the spring, Judge Mehnert and others from the court joined him for a paddle around the island.

“They talk to you like they’ve known you forever,” Loring said.

Feeling shunned by family, friends and neighbors is a major roadblock to recovery, Mehnert said. A person who feels alienated is more likely to self-medicate, “and it becomes a downward spiral,” he said. “If we can reintegrate that individual back into that community … we find that those supports exist beyond the time period of the program.”

There’s strength in carrying on positive traditions

Reintegration may be especially vital in Native American communities, which have long struggled with substance use and have seen a startling rise in overdose deaths in the past two decades.

American Indian and Alaska Native people living in rural areas of the United States experienced a more than a five-fold increase in such deaths between 1999 and 2015, the most dramatic increase of any race or ethnicity measured by the National Vital Statistics System. In 2015 in that group, there were nearly 20 such deaths per 100,000 people, a slightly higher rate than among rural white people.

There’s little reason to believe the situation is any less dire for Native Americans in Maine. The state’s overall rate of overdose deaths was among the highest in the nation in 2016, and it kept climbing last year even as other states saw the death rate begin to slow.

Efforts to stem drug use among Native people – among any group, it could be said – can’t focus only on equipping an individual with skills to manage the triggers of addiction or on changing long-standing patterns of harmful behavior, said Spero Manson, a professor of public health and psychiatry. Native Americans, in general, take a highly sociocentric view of personhood, said Manson, who directs the Centers for American Indian and Alaska Native Health at the University of Colorado Denver. A person’s self-identity, he said, is inextricably linked to the quality of their relationships and to the general health of the community.

The historical trauma that tribes experienced during colonization and the degree to which they were separated from their cultural roots continues to undermine their health, Manson said. (A 2013 paper on tribal drug courts described substance use and addiction as “lingering symptoms of conquest.”)

In addition to being hunted, quite literally, for decades in the 18th century, generations of Penobscot were forced to assimilate to white Western culture. They were enrolled in schools where they were punished for speaking their native language. They were shamed for their cultural practices and forced into foster care. The Wabanaki confederacy, of which Penobscot is a part, continues to experience “cultural genocide” through underlying discrimination at state institutions and ongoing legal disputes over land and water rights, a Wabanaki-state commission found in 2015.

That “marginalization steals from (Native people), if you will, many of the sources of individual and collective support that are so important to youth’s ability to navigate the pressures of contemporary life,” Manson said.

Many of the approximately 130 Healing to Wellness courts operated by federally recognized tribes within the United States create a kind of feedback loop, said Lauren van Schilfgaarde, an attorney with the Tribal Law and Policy Institute in California. Seeing fellow tribal members “sort of come back from the darkness” is healing for the community at large. So is ownership of a judicial system that accurately reflects their culture, especially for tribes that, even within their sovereign nations, were required to adopt Western styles of government.

Then there’s the strength that comes from teaching traditions that have been lost to many people.

“Penobscot is tapping into that,” van Schilfgaarde said.

A much needed light in the community

It’s difficult to say exactly how successful the court’s cultural components or its overall approach have been.

The tribe did not release the recidivism rate among the program’s graduates, though given the small size of the adult program – it can serve up to 10 people at a time – that figure may not be statistically significant. But researchers have repeatedly found that well-run drug courts are effective at reducing recidivism and promoting long-term recovery.

Penobscot’s cultural approach “can only help the model,” said Aaron Arnold, director of technical assistance at the Center for Court Innovation in New York.

Drug courts are known to do something else, too: save money.

A year’s worth of programming at the Penobscot court costs about $7,500 per participant, not including the cost of any required residential treatment. The price tag on a yearlong jail stay? About $40,000, Mehnert said. That difference matters to the tribe, which pays the county to incarcerate people for crimes committed on the reservation.

The Penobscot program is cost effective in part because many of the community leaders who make up the “wellness team” are employed by other departments within the reservation, including social services, housing, education, medical and behavioral health, and the police department. They do this work at no additional cost to the court.

Other tribes run similar drug courts, but is it a model that could work elsewhere? The Penobscot court is not so different from a community court, Arnold said, designed to work in the place where the people who come before the judge live, with ample wraparound services. Their numbers are growing across the country, though they are uncommon in rural areas.

Tipping, the case manager, would like to expand the court’s reach but is hamstrung, for now, by money and geography. She hopes to secure funding that allows the program to accept anyone from within the Wabanaki confederacy, which also includes the Micmac, Maliseet, Passamaquoddy and Abenaki tribes, if they live within reach.

There’s been talk of starting other tribal courts in the region, but in the most rural parts of the state, a shortage of necessary services, such as Alcoholics Anonymous meetings, prescribers of suboxone – a drug commonly used to treat opioid addiction – and substance-use counselors, makes that difficult.

The big dream? To start a residential treatment facility, where Penobscot and other Native Americans from the region could receive culturally relevant care.

“We know the need in our community is so high,” Tipping said.

Shining example of what this court can accomplish

In the months after Jon Loring’s home was seized, his 8-year-old son Lydon returned to the neighborhood to play with Shay’s son. He stood in Shay’s driveway, Shay recalled, and looked over at the house he used to live in.

Concern about the younger members of Penobscot Nation weighs heavy on Shay. He is president of Nibezun, a cultural exchange center located on the banks of the Penobscot River north of Indian Island, in Passadumkeag, where the sharing of traditional ways is seen as powerful medicine in itself. Shay said he imagines the Penobscot and other Native Americans standing at a 50-yard line. Behind them, are hundreds of years of oppression. In front, the next seven generations. With them, they carry all of the intergenerational traumatic stress that history has wrought.

“It’s all one-in-the-same sickness, but it has many symptoms,” Shay said. “We’re looking at it now. What’s the answer to the problem? The answer is to put the culture back into the next seven generations at every level that you possibly can.”

This summer, Jon Loring picked sweetgrass alongside his brother in a marsh near Bar Harbor, while Lydon and Mehnert searched for crabs nearby. With help from the court staff, he connected with a nutritionist to learn more about how to manage his diabetes. He began planning his “give-back,” a final community project, as he approaches graduation. And he talked with the court’s attorneys about becoming a mentor in the juvenile drug court.

“You have this pipe dream of what this program can offer somebody,” Tipping said, “and he’s living it.”

At a court session in July, Loring stood within the circle, hands clasped behind his back as he listened to Mehnert praise the craftsmanship of the feather fan he had brought in to show the court. Then Mehnert told him what a strong example he had become for his youngest son.

“He was going to follow you, whichever path you chose,” Mehnert said. “So, thank you.”

Loring responded, “You’re welcome.”