Given the historic droughts in the west, the drying up of the Great Salt Lake and the fights over the future of the Colorado River, you’ve probably heard by now that water is the new oil.

Twenty years ago the Moneyball guy told us this would be the case; before that (really long before that) the Roman philosopher Seneca reportedly said “where a spring rises or a water flows, there ought we to build altars and offer sacrifices.”

For most of human history, the proximity of freshwater has dictated where humans have settled and thrived, while too much of it (summer monsoons in the Cambodian city of Angkor) or too little (drought in the kingdom of the Maya in Mexico) has led to the collapse of numerous civilizations throughout the world.

In Maine, our problem often seems to be too much water (this summer’s damp and dreary June being a fresh example) rather than too little.

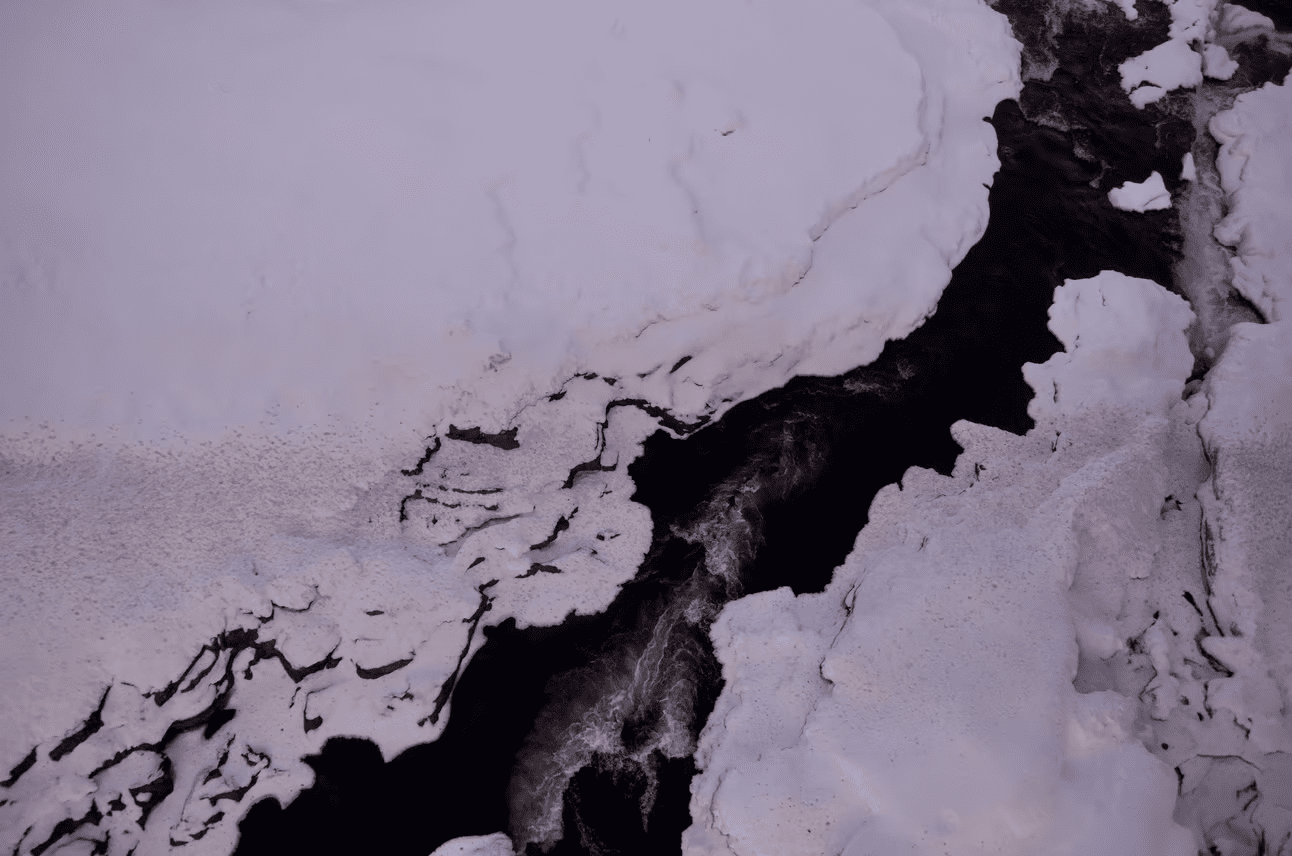

But the state is experiencing more frequent periods of drought and heavier bouts of precipitation, more of which is falling as rain and less as snow (snowmelt is one of the primary ways Maine’s groundwater aquifers are recharged).

As the Northeast becomes wetter and warmer with a changing climate, there may be increasing periods of imbalance, and shifts in the time of year when the water table is highest.

And as one of the few places in the world where access to fresh water seems like it won’t be a problem in the future, advocates say the state and municipalities should be doing more to safeguard and control such a precious resource.

They’ll have to wait: a bill that would have dramatically changed groundwater regulation and given municipalities more control over contracts with bottled water companies will be carried over to next session and looks likely to be watered down.

The bill proposed limiting contract terms between utilities and extraction companies to no longer than three years (that will likely be upped to seven years). The legislation also proposed requiring every municipality in a watershed to vote on extraction contracts, which, as Maine Public pointed out, would have been a dramatic shift in the how the state regulates groundwater.

That provision will likely be jettisoned after state officials and lawmakers worried about the size of watersheds (some, like the Penobscot River, cover huge portions of the state) and how they would determine which communities fall within their boundaries.

The legislation has faced opposition from (no surprise) bottled water companies, who say several years isn’t enough time to get back their investment. Utility operators also voiced opposition, saying that the revenue is essential for keeping costs down for ratepayers. They also argued that there are already protections in place to prevent overwhelming the resource.

Let’s talk about those protections, which were discussed in detail at a work session on the bill in mid-May.

Both the Maine Department of Environmental Protection and the Maine Department of Health and Human Services are involved in regulating groundwater extraction. There is some overlap of the agencies, but in general, DEP regulates those that meet the threshold for a significant well (more than 50,000 gallons a day or 75,000 per week) or that trigger what’s known as “Site Law,” which is any development that has a substantial impact on the environment. Public utilities are regulated by DHHS, which makes sure water is safe to drink.

One of the first things to know, said David Braley, director of the Telephone and Water Division of the Maine Public Utilities Commission, is that, by law, if there are any questions about water quantity, the public utility gets the water first.

Of the state’s 152 water utilities, five — North Berwick, Rumford, Lincoln, Kingfield and Fryeburg — have large-scale extraction permits, said Braley. Of those, four require what’s called a “bulk water transport permit,” which expires every three years. Four of the five permits are held by Poland Spring, said Braley.

To get the permit, a company has to prove that they’re not adversely impacting the aquifer they’re drawing from, other users of the aquifer or any natural resources that are supported by it (like streams or wetlands).

“So every three years,” said Braley, “They have to start over again and demonstrate that they haven’t had in the past, and they’re not going to have in the future, any negative impacts on the environment.”

The DEP monitors pumping rates and groundwater levels at least monthly, said Braley, and in areas where there have been concerns, such as in Hollis, DEP staff now have gauges to monitor as water levels rise and fall in real time.

(The Department drew the ire of residents after signing off on a permit for Poland Spring to double extraction at a well in Hollis from 30 to 60 million gallons during an ongoing drought last August; the company eventually withdrew its request.)

The US Geological Survey also monitors a small network of wells around the state that are far removed from any large-scale extraction, to help understand water levels outside of any impact zones. USGS is currently studying how changes in recharge patterns — such as snow melting earlier in the year — might affect groundwater extraction facilities, said John Hopeck, who handles groundwater monitoring and assessment for the DEP, during the work session.

“It’s not a question of the water not being there, it’s simply that this year is different. That’s what we expect to see with natural systems. Sometimes they behave in ways that are a little hard to capture in specific regulatory flow standards.”

Braley, who is a senior hydrogeologist, also tried last month to put to rest fears that Poland Spring had affected water levels at Round Pond in Fryeburg that arose at a public hearing in April.

“So in public hearing, what you’re saying is that the many citizens from Fryeburg who came to testify and showed us visuals of declining water in previously full ponds are mistaken and confused?” asked Rep. Valli Geiger, a Democrat from Rockland.

Braley hesitated for a moment. “Yes,” he said, and explained the geologic history of Round Pond, which some advocates have contended is being depleted by Poland Spring overdrawing an aquifer below.

“The water level in the pond is actually the water level of the groundwater there,” said Braley. It fluctuates with the seasons. “What they’re seeing there is the water levels going up and down naturally… it’s always been that way and it always be that way.”

Some legislators seemed comforted by what they heard during the work session.

“It’s clear that a number of agencies are routinely taking a look at whether or not the natural resource is being depleted,” said Rep. Walter Runte, Democrat from York.

But others pressed for Mainers to have more oversight and benefit. Except for property taxes and the jobs Poland Spring creates, said Geiger, the state “receives no benefit from what is a huge extraction business of a natural resource that belongs to the people of Maine. I think the very least we can do is have a pause every seven years to look at the contract.”

Geiger argued for communities to have a share of the profits, and took issue with the idea of any company “lock[ing] up huge amounts of water supplies for 25, 45 years.”

“I have friends in Colorado who are running out of water, and firmly believe that their situation will be fixed by running a pipe from states with lots of water,” she said during a public hearing on the bill in April.

Rep. Maggie O’Neil, a Democrat from Saco who sponsored the bill at the behest of advocates, said in a phone call this week that she wasn’t able to attend the work session and hadn’t yet seen the video but felt state agencies could still do more to safeguard the state’s groundwater.

“Our groundwater is a precious and finite resource that deserves protection,” she said.

If you’re interested in reading more, I wrote my master’s thesis in 2017 on a proposal by Poland Spring to drill a new well in Rumford.