Kayla Duvall knew she had to get out of her marriage.

If she didn’t answer her husband’s repeated phone calls, he grew angry. He accused her of lying or cheating if she turned off the tracking app on her phone. Once, Duvall said, she left their 9-year-old son home alone for an hour and her husband called the police and child protective services on her. At times during their 9-year marriage he became physically violent.

“There was so much gaslighting that he could have told me the sky was green and I would probably believe it until I saw it for myself,” said Duvall, now a criminal justice advocate for domestic abuse survivors in Franklin County.

Her divorce was finalized in February 2020, one month before Maine’s first COVID-19 case. If she was still married during the pandemic, Duvall said, it would have been “excruciating.” Seeing his name in a phone notification still gives her anxiety a year later.

The stress and isolation of the pandemic have made it more dangerous for survivors in similar situations.

“I can’t imagine still going through that during a pandemic,” said Duvall, who helps operate support hotlines for the nonprofit Safe Voices. “The folks that we talk to every day are so much stronger than most of them believe that they are.”

Advocates say COVID-19 did not cause abusive behavior, but stay-at-home orders and business closures heightened stress and increased barriers to some resources, which led to a 24 percent spike in calls with survivors in Maine during 2020. But, the pandemic also increased public awareness of domestic violence and expanded virtual access to resources.

The United Nations declared violence against women a “shadow pandemic,” citing cramped living conditions, isolation with abusers, movement restrictions and deserted public spaces as key factors.

And a report released last month by the National Commission on COVID-19 and Criminal Justice found an 8.1 percent increase in domestic violence nationally after pandemic-related stay-at-home orders. The study examined data from crime reports, emergency hotlines, hospitals and other administrative documents.

“Stay-at-home orders and the pandemic’s economic impacts exacerbated factors that tend to be associated with (domestic) violence: increased male unemployment, stress associated with childcare and homeschooling, increased financial insecurity, and poor coping strategies, including the increased use of alcohol and other substances,” according to the study.

Regina Rooney, communications director for the Maine Coalition to End Domestic Violence, said the pandemic highlighted parts of society that were deficient before COVID-19.

“We have seen where we are strong and where we can come together. We have seen where there are gaps in the systems and the safety nets that we need to hold each other up when times are hard. And that is true for domestic abuse and violence,” Rooney said. “I really hope that we don’t forget the lessons that we have learned in COVID-19.”

Twenty people per minute face domestic violence

Domestic violence rates in Maine declined multiple years in a row before COVID-19, including a 12 percent drop in 2018, but advocates say report records are only “the tip of the iceberg.”

“On average, nearly 20 people per minute are physically abused by an intimate partner in the United States,” according to the National Coalition Against Domestic Violence. “During one year, this equates to more than 10 million women and men.”

In 2019, nearly 3,700 reported assaults occurred between household or family members in Maine, according to the Department of Public Safety’s latest annual report.

Rooney said it’s hard to track rates of domestic violence and compare them to other states because stigma and fear prevent people from reporting abuse. In addition, Rooney said only about half of survivors who experience criminal violence turn to law enforcement for help.

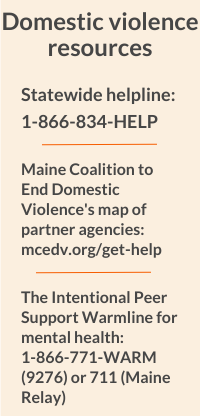

The Maine Coalition to End Domestic Violence leads statewide advocacy and trains nine partner agencies, which provide direct services such as answering helplines, locating shelter and offering legal support. These member organizations, which include Safe Voices, assist about 13,000 Mainers each year.

COVID-19 heightened stress and increased barriers to resources, but isolation wasn’t a new challenge for domestic violence survivors, Rooney said.

“While it is extremely true that COVID-19 has increased isolation for survivors of domestic abuse and for their children, they have been dealing with isolation all along. It’s a key tactic of abusive people,” Rooney said.

‘But home isn’t safe’

When the coronavirus reached Maine last year, the hotlines went dead. Calls for assistance initially dropped off “steeply, in a way that was scary” during the first weeks of the pandemic, Rooney said.

Total contacts with survivors in April — the first full month of the pandemic — were down 39 percent compared to April 2019. Shelter requests were down 55 percent and helpline calls were down 15 percent during that period.

The same phenomenon occurred nationally, with the National Domestic Violence Hotline reporting a 52 percent drop in calls between March 10 and 24.

The decrease could be because survivors of domestic abuse, like most other Mainers, were preoccupied with concerns about the pandemic, employment situations and remote learning, Rooney said. Or they may have assumed the helplines, like everything else, were closed.

“It definitely creates some worry because we know that the violence didn’t decrease, right?” Duvall said. “The violence didn’t slow down as the stressors in folks’ lives increased. That’s just not how that works.”

After a month, the calls rebounded. Helpline calls, texts and emails increased 49 percent between April and June 2020 compared to the same time in 2019. For all of 2020, calls with survivors were up 24 percent and time spent on the calls increased 22 percent, according to the Maine Coalition to End Domestic Violence. Some of that is likely tied to the temporary suspension of many in-person services, but the length of the calls indicates the needs were greater and required more assistance.

About 78 percent of survivors contacted by the Maine Coalition to End Domestic Violence between March and October said the pandemic had affected their safety. And 73 percent said they had greater safety concerns due to social distancing and COVID-19.

Helpline workers noted an anecdotal increase in strangulation calls, Rooney said, which is “a high indicator of potential lethality,” demonstrating that abusive behavior has escalated. She was careful to note, however, that while stress from the pandemic or unemployment may contribute to escalated behavior, they don’t cause abuse to happen in the first place. “But they make already dangerous situations more dangerous.”

Despite the increase of calls in Maine, about 1,200 fewer people reached out for help in 2020 than 2019. There could be a number of explanations, Rooney said. For example, someone who normally would have called regarding a family matters court case may not have reached out if their case halted during the pandemic. Another who would have called for support because they were thinking of leaving their partner may have decided to stay during the stressful time.

With more people at home working and learning remotely, Duvall said advocates had to get “creative” to reach survivors. They found windows of safe time, such as when a survivor was grocery shopping. Building trust over the phone is more difficult than in-person, Duvall said, so she set up Zoom meetings with survivors. But, some don’t have internet access or a safe place to conduct virtual meetings.

Duvall said the hardest calls are from people who can feel their situation getting more dangerous and are looking for a place to go, but the options are limited due to COVID-19 restrictions on shelter capacity and indoor gatherings.

“The calls where the caller is feeling very overwhelmed because they now have to use their home base for everything,” Duvall said. “They’re working from home, they’re teaching their kids from home, but home isn’t safe. And they don’t have a way out of that.”

Advocates help survivors come up with a plan for how they can stay safe in their unsafe situation. This might include identifying a neighbor who could call 911 or establishing a secret phrase their family member will recognize as a request for help.

“It never fails to amaze me how unbelievably resilient and strong survivors are,” Duvall said. “They are surviving in unsafe situations every day and they’re actively engaged in helping keep themselves safe until they are able to leave.”

‘It’s never as easy as just leaving’

When Duvall tells clients vague versions of her story, they are surprised to hear she knows what they’re going through. Duvall said she had multiple safety nets when she left her husband: her own vehicle, her own bank account, a supportive family and somewhere to go. And she says it still took her nine years to leave.

Others don’t have those same safety nets, which is why it bothers Duvall when people say, “Why don’t they just leave the abusive situation?”

If the abusive partner controls the bank accounts and the one car, alienates your friends and family, and threatens to take your kids, “and every time you call about shelter space, they’re all full — where are you going to go?” Duvall said. “What are you going to do? Are you going to pack up all your kids and walk down the street with no money and no car with no place to go? It’s never as easy as just leaving. It’s just not that easy.”

One positive thing that has come out of the pandemic is the increased access to virtual resources such as electronic filing and support groups, Duvall said. She hopes these continue after the pandemic.

Rooney said the public seems more aware and concerned about families experiencing domestic violence. People have donated, volunteered and attended training. Communities play an important role in supporting domestic abuse survivors, she said, and over the past year, she’s seen a “deepening commitment” to those experiencing abuse.

“I am hopeful that going forward, people will remember that when the pandemic is done, domestic violence isn’t going away,” Rooney said. “It was here before the pandemic, and it will still be here after the pandemic.”