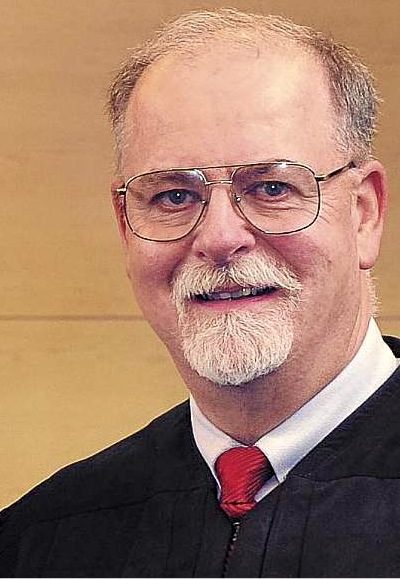

It was a typical Monday morning for Charles LaVerdiere, chief judge for the Maine District Court: He presided at Waterville District Court, facing 125 people who needed to be arraigned between 8:30 and 11:30 a.m.

One by one, LaVerdiere informed each defendant of the charges for crimes ranging from simple theft to shoplifting, to OUIs, to domestic violence and assaults.

For more than a decade, LaVerdiere has dealt with thousands of defendants and hundreds of lawyers in his courtrooms, and in each case he has a lot on his mind: from making sure a defendant knows his rights, to constitutional issues, to setting a neutral tone — and doing it all quickly, with the weight of so many cases in so little time.

In the midst of all that comes restitution — a court order given to a convicted criminal to repay a victim for damages.

Later that week, in his office at the Maine Judicial Center in Augusta, he reflected on the concept of making victims whole through restitution.

“First of all, we recognize there is a loss,” he said. “And we recognize that when somebody has been violated by a crime, that it is an emotional as well as a financial hardship.”

The goal is “to do as much as the court can to collect what can be collected on behalf of victims.”

Still, the judge said, crime victims in Maine “need to be realistic about the fact that an award of restitution in a case does not necessarily translate to their receiving all of that money.”

A Maine Center for Public Interest Reporting investigation has found that the state system for compensating victims of non-violent crimes is overburdened, uncoordinated and promises what it can’t deliver. For example, in Cumberland County alone, convicted criminals are $2.6 million behind on restitution payments.

“The system is imperfect and we know it,” Judge LaVerdiere said.

He said that as a judge in Maine, he’s found that the “vast majority” of people who come to court and agree to restitution payments find out later that they don’t have the ability to pay as promised.

“Many of them are indigent, many are hopeful they will become employed or that they will have the resources from one source or another to be able to pay,” he said, and a “very large percentage” of defendants are so poor they apply for free legal services by a court-appointed attorney.

Then why give sentences that include restitution? LaVerdiere said a judge’s role in restitution is confined by current law and past judicial decisions. For example, when it comes to the plea deals brought before him that may include orders of restitution, he can only accept or reject those deals.

His responsibility is not to investigate a defendant’s finances, but to act as a neutral party, make sure that the sentence fits the crime and that proceedings are carried out within the letter of the law.

Judge LaVerdiere said the Maine legislature in 1977 enacted the state’s restitution system as ancillary, or secondary, to the central objectives of criminal law.

Restitution, said LaVerdiere, is meant to “instill some responsibility on the part of the individual who committed the offense.”

“Restitution is oftentimes difficult simply because, despite the person’s interest in paying, they just don’t have that ability,” he said.

Hoping that the offender will one day pay restitution “is frustrating for victims, it is frustrating for DAs, it is frustrating for courts,” LaVerdiere said.

The making of the plea

Typically, the vast majority of sentences that include restitution also involve a plea agreement negotiated between the district attorney’s office and either the defendant’s counsel or the defendant directly, Judge LaVerdiere said.

If the judge accepts it, then restitution becomes part of sentence.

If the judge rejects the plea, then further negotiation would occur and be brought before the judge for his consideration.

The case could go to trial, and if the “person is found to have committed the offense,” said LaVerdiere, “you’re again faced with the question of the amount that defendant can pay.”

During the behind-the-scenes plea agreements, defendants will often agree to restitution orders in exchange for reduced sentences — a process that happens far from the eyes of the judge, said Maine Commission on Indigent Legal Services Executive Director John Pelletier.

“The judge is not listening to one lawyer saying, ‘The restitution is wrong,’ or ‘The client can’t afford it,’” said Pelletier. “The prosecutor is saying: ‘This is why we need restitution’. Often the judge is not making a decision made on arguments; the judge is approving an agreement that’s been made.”

There’s a “large incentive” for defendants participating in plea agreements to agree to restitution, said Pelletier, because it “generally makes prosecutors much more willing to forgo other aspects of the sentence if they can get that restitution order.”

“You know, in frank terms, if the restitution is agreed to, and if it’s paid up front, there’s often less jail time, or the fine might be less,” Pelletier said.

Maine statute requires that the court consider a person’s “present and future financial capacity” to pay restitution, Pelletier said.

“If a person in front of the court is able-bodied and has a potential to find a job,” that can be enough for establishing that ability to pay, Pelletier said.

At the same time, if a defendant in Maine says he has the ability to pay back restitution, he must be taken at his word, said LaVerdiere, citing the criminal code and past court decisions. There is no financial screening process.

Poor defendants “are often uneducated and have barriers to employment,” Pelletier said.

“It’s often the case that … paying all the restitution is not a realistic outcome for this individual,” Pelletier added. “I think that restitution gets quite a high priority from the courts and the prosecutors, so I think the determination of ability to pay is often made with some optimism.”

‘I can’t tell you …’

LaVerdiere said he cannot estimate how many people pay restitution in full.

“The only ones who the court sees are ones who are in default,” he said. “I can’t tell you if the vast majority of people pay restitution and never come back to court. Or whether all the people I see are highly representative of the group as a whole.”

Currently, each DA’s office is responsible for maintaining all of its own information when it comes to how much restitution is owed. The state court system does not maintain such data, LaVerdiere said.

The Maine legislature recently approved paying for a new case management system for the courts.

LaVerdiere said the new system will allow courts to better know how many people are ordered to pay restitution, and transmit restitution orders directly to the DA’s office at the time of judgment.

“We will be able to electronically send information with regard to restitution to the Department of Corrections, to district attorneys, to victim advocates and others,” LaVerdiere said, noting that now such information is shared manually. “That manual system is not the greatest.”

‘It’s a resource issue’

LaVerdiere said it’s tough for victims to accept their restitution may never be paid in full.

“Unfortunately, there is no system that would allow us to guarantee every victim that they would be able to be reimbursed,” he said, noting that victims of crime may have options like insurance or lawsuits to recover losses.

The judge said that though 100 percent collection is unlikely, the state’s system to assist crime victims owed restitution can improve. Enforcing and collecting restitution orders often boils down to a question of time and resources, said LaVerdiere, addressing a balancing act he knows well as a judge.

“It’s a resource issue,” said LaVerdiere.

“But”, said the judge, “we are again in a situation where the resources that we have available to be able to devote to this are limited. And we find that again a large portion of people just don’t have the ability to pay, no matter what the process is that we use.”

When it comes to restitution, the Maine criminal code is primarily focused on the defendant’s ability to pay, LaVerdiere said.

A 2013 Maine Law Review article noted that in Maine’s criminal restitution system, defendants are given “near-endless extensions” to pay back restitution, while victims have fewer procedural rights in comparison.

“That’s a policy issue that the legislature has grappled with in the past and I’m sure will grapple with in the future,” LaVerdiere said. “Until that law is changed, that’s the focus we have to place when making our decisions.”

Nation has same problem as Maine

There’s no reliable national data about how well states set, enforce and collect victim restitution.

But, National Crime Victim Law Institute Executive Director Meg Garvin said, based on her research, the enforcement of restitution nationwide is poor.

“Restitution isn’t ordered in high enough dollar numbers, even when it’s ordered,” said Garvin, a clinical professor of law at Lewis & Clark Law School. “In actuality, victims are carrying the financial burdens of their own victimizations.”

Similarly, there’s scant state or national data on the cost of crime for victims, though a 1996 U.S. Department of Justice’s National Institute of Justice report estimated it at $105 billion a year, including medical expenses, lost earnings and public victim assistance costs.

Most states don’t have “someone whose job it is to collect and enforce,” Garvin said. “It’s everyone’s job, so it’s no one’s job. Victims are left without any champion to secure restitution.”

Some states have come up with creative solutions to collect more restitution for victims, said Garvin.

States are doing everything from using state or private collection agencies, to extending a non-paying offender’s probation time, to consolidating all of an offender’s legal obligations into one system to better collect restitution, according to a 2002 report by the U.S. Department of Justice’s Office for Victims of Crime.

In Vermont, in 2002 the legislature created the State of Vermont Restitution Unit, which operates as a statewide collections agency that enforces and collects criminal-court ordered restitution.

The unit also has a special fund through which it can advance up to $10,000 in restitution payments to individual crime victims, no matter if the crime was violent or nonviolent. The fund is paid for by a 15 percent surcharge added to all criminal and traffic fines.

The unit has increased the overall collection rate to 24 percent in 2011 from a low of 13 percent in 2001, according to a 2011 National Center for Victims of Crime report and the 2001 Vermont state auditor’s report, “Vermont’s Restitution System: Failing the Victim.”

In Rhode Island, victims can sign up at a Victim Assistance Portal, that allows victims to access pertinent information on the defendant’s case – including restitution payments.

In Alameda County, California, the district attorney has its own restitution unit that says it “actively monitors” probation cases where restitution of more than $1,000 is ordered. The county’s central collections and department of corrections have a 55 percent recovery rate for crime victims, collecting $19 million out of $34 million ordered in Alameda County from June 2001 to June 2006.

Hawaii looked at barriers to enforcing restitution in 2012, finding weak enforcement for offenders behind bars and a lack of coordination across courts ordering restitution and the criminal justice agencies responsible for collecting it.

“As a result, essential questions about the enforcement of restitution orders, such as the amount of restitution ordered that is collected each year, could not be answered,” according to a Council of State Governments Justice Center press release.

Hawaiian state legislators then passed legislation increasing restitution collection in prisons and spending more than $1 million to create 22 new victim services positions at the state and local level. Along with a $367,767 grant from the Department of Justice, the state spent an additional $100,000 to develop a database to collect restitution data.

Maine has also taken on the issue, to an extent. When the Department of Corrections takes money from a prisoner’s account, restitution is a higher priority for collections than all other legal fines, child support and alimony.

The legislature in 2003 enacted a law saying if a victim cannot be located, whatever money has been collected as restitution must be forwarded to the Treasurer of State as unclaimed property.

The Maine Coastal Regional Reentry Center expects inmates to find employment, meet restitution and fine obligations and create a savings account. Last year, 57 male, non-violent offenders paid over $22,000 in restitution to victims.