Central Maine Power Co. and its parent company funneled thousands of dollars through the Maine State Chamber of Commerce to tout a construction plan to bring Canadian hydropower to Massachusetts through western Maine — a project that’s expected to earn the utility $1.95 billion over the next 20 years.

The financial ties between the utility and chamber were obscured by tax laws that do not require nonprofits like the chamber to disclose their funders.

CMP and Avangrid Inc., the company that owns it, also skirted campaign finance disclosures because much of the chamber-involved activity occurred before a referendum calling project permits into question qualified for the ballot in March. Reporting thresholds are only triggered if a group spends money to initiate or influence a campaign, which is defined as giving direct “yes” or “no” voting orders.

The obscured spending comes on top of nearly $11.3 million the utility’s affiliated political action committee, Clean Energy Matters, poured into the race, which broke Maine’s record for spending on one side of a referendum, let alone by one group.

The utility coordinated the dark money through a coalition the Maine State Chamber of Commerce formed in 2018 called Mainers for Clean Energy Jobs.

This coalition spent nearly $10,000 on advertising — $7,280 on Facebook ads between December 2018 and May 2019, and $2,000 on radio ads, according to public filings from the Federal Communications Commission and Facebook’s Ad Library.

Because the coalition is not registered as a political committee, additional spending and sources of funding are mostly unknown.

Some of that undocumented spending supported at least six telephone town halls inviting Maine citizens to join Mainers for Clean Energy Jobs’ director, Ben Dudley, in live discussions about the merits of the corridor. Dudley said the calls reached “thousands” of Mainers each time but would not provide exact numbers. Six robocall campaigns could cost between $18,000 and $60,000 to call between 5,000 and 100,000 people, according to two companies that specialize in the technology. At least one of the Mainers for Clean Energy Jobs’ robocalls came after the referendum qualified for the ballot.

Though Avangrid and CMP’s names do not appear as donors on filings connected to Mainers for Clean Energy Jobs, the chamber’s lawyer, Ben Gilman, confirmed Mainers for Clean Energy Jobs is “funded by the Maine State Chamber of Commerce with support from CMP and Avangrid,” and specifically noted that Avangrid funded the telephone town halls.

CMP’s spokesperson, Catharine Hartnett, declined to respond to questions about whether the utility financed Mainers for Clean Energy Jobs or how much it paid the coalition. Thorn Dickinson, president of the branch of the utility overseeing the NECEC project, would only comment on financial transactions running the other direction — from the Maine State Chamber of Commerce to the utility’s PAC, which are documented on ethics reports and total around $2,000.

Mainers for Clean Energy Jobs was less than a month away from disclosing its funders to the Maine Ethics Commission in campaign finance filings when the state’s high court ruled the referendum unconstitutional, killing the ballot measure and making it no longer necessary for the coalition to file.

Lawyers for the CMP-affiliated political action committee, Clean Energy Matters, planned to have Mainers for Clean Energy Jobs register as a committee itself or “assimilate all of the activity supportive of the project under one entity – presumably Clean Energy Matters,” by Sept. 7, according to Gilman.

“That is now moot,” Gilman wrote in an email to The Maine Monitor.

Sept. 7 was the day that new ethics guidelines — approved just two days before the court ruling — would have kicked in. The new guidelines said any group spending $500 or more on communication related to the corridor or hydropower that close to election day was doing so “with intent to influence.”

Jonathan Wayne, executive director of the ethics commission, said the rules were “not really prompted by the large amount of money that’s being spent related to the corridor,” but by an influx of ambiguous advertising related to the project.

“This is about making organizations understand that sometimes their paid communications to voters relating to a citizen initiative have to be reported as expenditures in campaign finance reports, even if the communications don’t expressly advocate for or against the ballot question,” Wayne said, before the court ruling.

But after Maine’s high court struck down the referendum, the commission said it could no longer mandate disclosure from Mainers for Clean Energy Jobs.

“Without there being a referendum, there is no campaign for our purposes, so there’s no requirement that they register and report to us,” said Michael Dunn, the ethics commission’s political committee and lobbyist registrar. “It’s generally — fundamentally — unfair to change the rules mid-game.”

What is Mainers for Clean Energy Jobs?

In addition to lending its name and personnel to Avangrid and CMP-funded advertisements, Mainers for Clean Energy Jobs has worked alongside the utility for two years to drum up support for the corridor project in other ways.

The coalition was formed as an arm of the Maine State Chamber of Commerce in 2018. Its 30 members include unions, businesses, lobbying organizations and veteran environmental leaders. While CMP is not listed as a member of Mainers for Clean Energy Jobs, its president, Douglas Herling, sits on the chamber’s board.

Only one person makes up Mainers for Clean Energy Jobs’ staff — its director, Ben Dudley.

Who funds Dudley’s pay — and its amount — is not revealed in public filings. The chamber’s most recent 990 — its nonprofit tax filing — covers the period before the coalition was created, July 2017 to June 2018, and does not include Dudley among its compensated officers. Gilman said the state chamber of commerce has Dudley on a retainer.

The Maine Monitor requested the chamber’s 2018-19 filings and did not receive them in time for publication.

Mainers for Clean Energy Jobs’ aim is to educate regulators and the public about the benefits of the New England Clean Energy Connect project, which the coalition says will provide 1,600 short-term jobs, positive climate impacts and a $1 billion economic boost for Maine over 10 years — among other items outlined on its website.

When the coalition was formed, its efforts focused on supporting proposals pending before the Legislature and permitting applications to the Public Utilities Commission, Department of Environmental Protection, Army Corps of Engineers and various Maine towns.

“Our job is to make the case for the project. It’s not our job to make the case for how people should vote one way or the other,” said Dudley, a former state legislator and chairman of the Maine Democratic Party from 2006-7.

RELATED: Listen to one of Mainers for Clean Energy Jobs’ tele town halls, from Feb. 19, 2020

When the Legislature was considering an independent greenhouse gas study of the project in February 2019, Dudley fought on behalf of the coalition to make sure it wasn’t conducted. (The bill ultimately failed; the study was never conducted.)

Dudley lobbied alongside CMP to kill the greenhouse gas bill and two others seeking to give Mainers a vote on where for-profit transmission lines would be built in 2019. Both were vetoed by Gov. Janet Mills.

Dudley’s lobbyist reports between March and June of 2019 indicate the Maine State Chamber of Commerce paid him $5,500 for the work, but it remains unclear whether CMP or Avangrid provided the funding to the chamber.

Dudley’s lobbyist reports between March and June of 2019 indicate the Maine State Chamber of Commerce paid him $5,500 for the work, but it remains unclear whether CMP or Avangrid provided the funding to the chamber.

The Chamber’s IRS designation as a 501(c)(6) allows the nonprofit to lobby as long as it doesn’t spend more than 40% of its expenses on political campaigning.

To avoid crossing that threshold, 501(c) groups can mask political activity by categorizing what some may consider to be political expenses as “educational” or “membership-building.”

“If you’re really trying to cultivate public sentiment for or against some project, you can often get your message out without triggering mandatory disclosure,” said John Brautigam, who has practiced campaign finance and election law for over 20 years. “Many people think this is a weakness in this disclosure system.”

On the federal level, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce has hid political agendas by not disclosing donors and touting educational or advocacy agendas in lieu of presenting itself as trying to influence candidate elections or referenda.

CMP’s battle for the corridor

CMP and Avangrid have mounted a concerted effort to build the corridor, pouring money into advertising and lobbying campaigns every step of the way.

The utility hired a team of lobbyists and lawyers in 2019 to defeat three bills — the same three Dudley lobbied against. One would have required an independent greenhouse gas study of the project and the others would have given Maine communities more say in the corridor route and use of eminent domain. That year, CMP spent more than $100,000 on lobbying, including on non-corridor efforts such as blocking the formation of a consumer-owned utility.

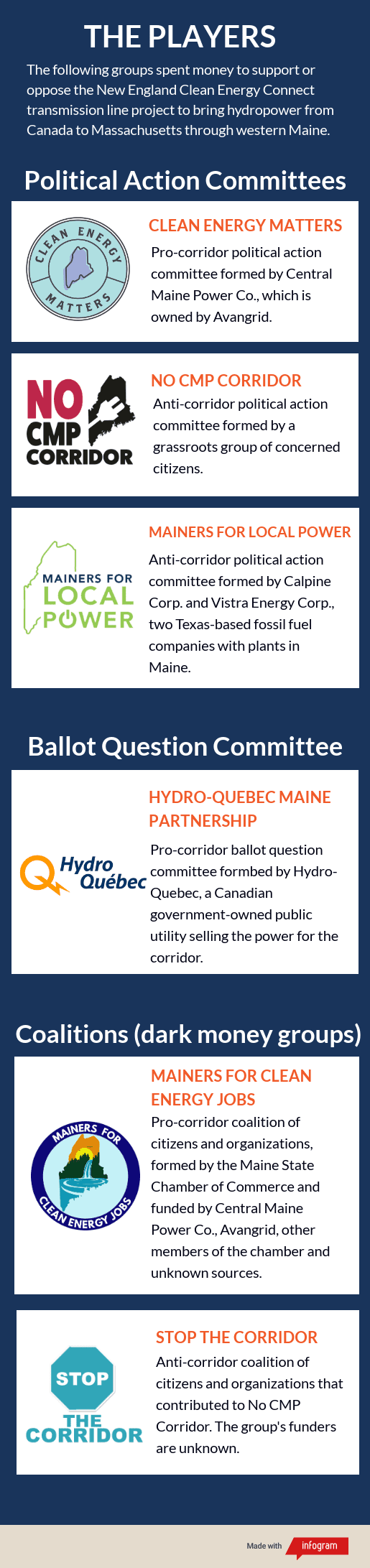

As organizers started gathering signatures to put the corridor project on the November 2020 ballot, CMP and Avangrid formed their political action committee, Clean Energy Matters. Once its opponents submitted the signatures, the PAC first challenged their validity, then challenged the validity of the ballot question itself — and won.

The referendum sought to ask voters whether to overturn the PUC’s decision to grant the project permits. Maine’s Supreme Judicial Court ruled it unconstitutional for citizens to be able to overturn the PUC’s decision because it oversteps the decision-making authority granted to the agency by the Legislature.

Of the nearly $11.6 million Clean Energy Matters has raised, CMP contributed more than $7.5 million and Avangrid gave more than $4 million. The PAC has spent just under $11.3 million.

The money CMP and Avangrid have spent on winning approval for the corridor has concerned some Mainers.

Betty Anne Listowich, who lives in Freeman Township in Western Maine, said CMP and Avangrid’s spending outside their PAC was troublesome.

“The dark money is the corporate greed,” said Listowich, who says she’s concerned about the corridor cutting through Franklin County. “If you could spend $17 million trying to wash this pill down my throat, what are you hiding?”

The $17 million includes over $11 million spent by Clean Energy Matters and over $6 million spent by Hydro-Quebec’s own ballot question committee. Hydro-Quebec is the government corporation selling the power.

A primary purpose of the New England Clean Energy Connect project is to transfer hydropower from Quebec to Massachusetts to support the Bay State’s ambitious clean energy goals. The New England Clean Energy Connect website claims the project will create 2,000 full-time jobs in Massachusetts and will save the state’s residents $150 million in electricity costs each year.

On the benefit page for Maine, the website claims Mainers will save between $14 million and $44 million in electricity costs each year and that the project will create 1,600 jobs during the construction of the corridor.

Not the only dark money group

Mainers for Clean Energy Jobs is not the only dark money group surrounding the corridor project.

The ethics commission is investigating a group called Stop the Corridor, which reported $85,000 of in-kind contributions to No CMP Corridor, an anti-corridor PAC. This included nearly $19,000 worth of staff time for “campaign coordination” and more than $48,000 for “volunteer recruitment,” according to No CMP Corridor’s campaign finance filings between October 1, 2019 and March 31.

The group also spent more than $1 million on advertising since 2019 — $1,034,000 on television advertising and $424,997 on Facebook ads.

Clean Energy Matters, which spurred the ethics investigation by filing a campaign finance complaint, alleges Stop the Corridor exceeded the spending threshold to disclose its funders.

When it announced the complaint in January, Clean Energy Matters cited concerns that out-of-state fossil fuel companies , which stand to lose millions of dollars if the clean energy project is built, were funding Stop the Corridor.

Stop the Corridor’s representatives have repeatedly declined to reveal its donors, most recently suing the Ethics Commission in June on the grounds that the commission does not have jurisdiction to investigate its finances. The commission ordered Stop the Corridor to disclose its funders in May so it could investigate whether it violated the law.

Katherine Knox, counsel for Stop the Corridor, has maintained the spending also does not meet the definition of “initiating or influencing an election,” because it funded efforts to block the project via the permitting process instead of the electoral process.

Knox did not respond to multiple calls and an email requesting comment.

“In this case, Stop the Corridor would have us believe that it is a ‘concerned coalition’ that has nothing to do with trying to influence a potential ballot campaign. But if you look at these ethics reports — or simply turn on your TV — it’s clear that their mission is to influence voters, ” said the Clean Energy Matters executive director, Jon Breed, in a news release announcing the complaint.

Though the referendum on the corridor has been struck down, Brautigam, the elections and campaign finance lawyer, said the record spending around the issue will create a legacy.

“It is nearly unprecedented in terms of the size and scope of the communications that (were) being made, to influence public opinion and arguably, at least in some cases, to influence voters as they go to the ballot box,” he said.

“Not only has the corridor itself been a subject of public debate, but all of this money has become an important and significant secondary public debate.”