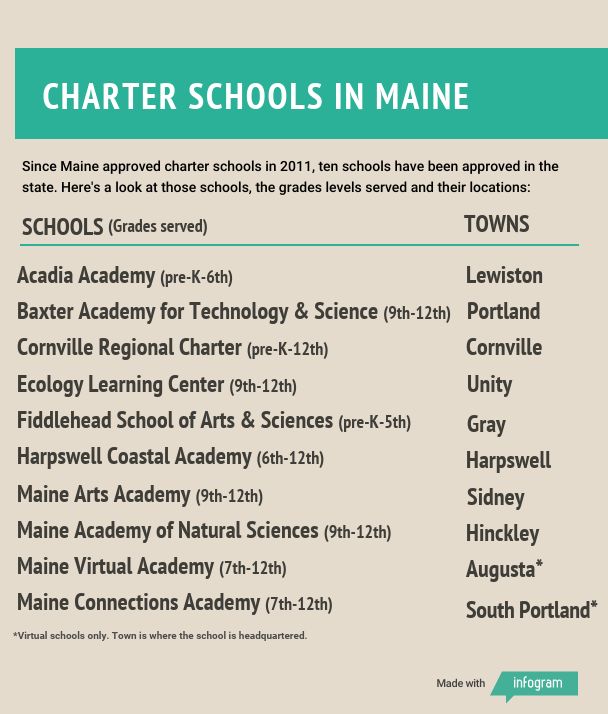

The Ecology Learning Center will officially become the 10th and final charter school to open in Maine.

The Maine Charter School Commission voted unanimously Tuesday to authorize a charter for the proposed high school, which is scheduled to open in the fall of 2020 in Waldo County. The decision means Maine has reached its statutorily mandated cap on charter schools and cannot open more unless legislators lift the cap or a charter school in the state closes.

“I feel grateful that we have this opportunity, (and) that we can have this 10th spot. This is not a quick, rash dream. This is something that’s been well thought out,” said school founder Lisa Packard.

Prior to the vote, several commission members expressed their support for the new school, including Jana Lapoint, a founding member of the commission who has been involved in the selection of all 10 schools. She praised the school for what she described as a “strong and diverse board” and for the school’s mission to focus on farming and forestry in Waldo County. She said the school may be surprised at the level of interest by students and parents.

“You may reach your numbers much sooner than expected,” Lapoint said during Tuesday’s commission meeting at the Augusta Civic Center.

The Ecology Learning Center will use a “place-based” education model, which was developed by David Sobel at Antioch University New England and who wrote a letter of support for the school during the nearly nine-month application process. The school is designed to be environmentally minded with curriculum and apprenticeships centered on solving ecological problems in Waldo County.

The Ecology Learning Center will use a “place-based” education model, which was developed by David Sobel at Antioch University New England and who wrote a letter of support for the school during the nearly nine-month application process. The school is designed to be environmentally minded with curriculum and apprenticeships centered on solving ecological problems in Waldo County.

In an area of the state with a long agricultural history and a place still attractive to families who want to homestead, Packard is striving to establish a school that prepares students to continue the farming legacy of the area and be college-bound entrepreneurs.

“It really has to do with homesteading and a focus on agriculture, and I think that there is a need in that community for more choices that align with the value of homesteading: to use your hands to build and farm and live well,” Packard said.

Born in Maine, but raised in Connecticut, Packard’s family has “long roots” in Maine and public education.

Her grandmother, who lived to be 103, was a public school music teacher and modeled a love for the environment during long walks in the woods. Packard followed in her grandmother’s footsteps teaching sixth grade in a Phoenix public school with Teach for America for two years, while earning her K-8 teaching certificate.

Packard returned to Arizona to complete a master’s degree in environmental education at Prescott College, and she spent the next decade there launching a school garden program, mentoring young teachers and raising her two sons. It was during that time that she was also introduced to charter schools.

“They were everywhere,” Packard recalled of Arizona’s charter school system, which she enrolled her sons in. “I think there were more charter schools than district schools.”

Approximately 17 percent of Arizona’s 1.1 million public K-12 students currently attend a public charter school. The state’s 1,424 district schools still outnumber the 559 charter schools in the state, though, enrollment at charter schools has continuously grown.

In comparison, approximately one percent of Maine’s 182,000 public school students attended one of its nine charter schools during the 2017-2018 school year.

What Packard fell in love with was the flexibility and innovation occurring at charter schools. Since moving back to Maine in 2010, she has closely followed the Maine Charter School Commission and state legislation that passed in 2011, which allowed charter schools to be formed in Maine.

In the past eight years, however, there has been a dramatic shift in the political climate surrounding charter schools in Maine, and top education lawmakers voiced their intent last month to seek to close low-performing charter schools as early as 2020.

The threat of political action against charter schools is not a concern to Packard or the start-up team with the Ecology Learning Center, she said.

“I don’t feel intimidated right now, because I would want the state to hold us to a high standard,” Packard said.

Chartering a community school

Packard believes that charter schools should be small and designed to serve the needs of the community they are in.

Packard said during multiple rounds of interviews with the Maine Charter School Commission that the Ecology Learning Center was specifically designed to address the needs of Waldo County students and to provide a high school option for home-schooling families in RSU3, which offers one public high school in Thorndike.

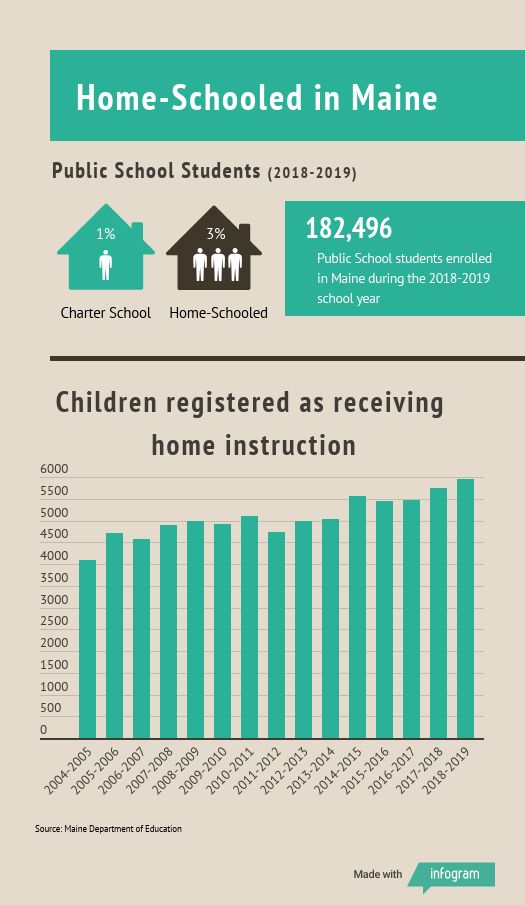

Last school year, there were 5,963 children participating in home education, according to the Maine Department of Education.

Last school year, there were 5,963 children participating in home education, according to the Maine Department of Education.

Packard launched the Ecology Bridge Program, a home school enrichment program for seventh through 10th grade, during the 2018-2019 school year to pilot the high school’s curriculum.

“We did learn a lot and it definitely informed our application. It was like hands-on learning,” Packard said.

The bridge program revealed students had varied writing skills — including some students with “weak” and “very weak” writing abilities — prompting the program to change its proposed daily schedule so that students started every day with a reading and writing block, Packard said. The program also piloted a topic rotation of “food” in the fall, “shelter” in the winter and “water” in the spring, which received a positive response from students and parents and will carry forward with the school.

The bridge program will reopen for another school year on Sept. 23, after the majority of its participants are done with the Common Ground Fair.

The advantage of transitioning the program to a charter school is that it will enable students to attend for free. Currently, the program is financed by a sliding tuition scale based on the family’s income.

“It’s really for financial access and it’s about closing that gap. What if you’re a student in Waldo County and you really want a different choice?” Packard said. “I believe in public education, because it makes it so everyone can join.”

The Ecology Learning Center anticipates opening with between 36 and 48 ninth and 10th grade students in the fall of 2020 and reaching a maximum enrollment of 96 students when it expands to all four grades by year three. All charter schools, by law, are open to students from anywhere in the state and of all abilities.

Open enrollment for the school is anticipated to start in February 2020.

Shortly before the vote, Maine Charter School Commission member Shelley Reed, who served as the commission’s non-voting liaison on the selection committee for the Ecology Learning Center, praised the center for its bridge program, saying it will give them a leg up when school the opens.

“This school really understands the population it’s going to serve,” Reed said. “I wholeheartedly support the Ecology Learning Center as our 10th school. It’s exciting.”