The local nonprofit managing conserved land on Sears Island said it was blindsided by a proposal commissioned by the Mills administration to use part of the island as a hub to assemble massive floating wind turbines. The group wants the state to pursue an alternate location.

“It just felt like we should have known that Sears Island was one of the two places that they were focusing on. We didn’t have a clue,” said Susan White, president of Friends of Sears Island.

A consultant notified the group regarding the recommendation that part of the island be used for a commercial offshore wind facility a week before the document was set to be made public, said White.

The study, which has been underway for months, came out just before Thanksgiving. The Friends group also said it was not told the plans would be discussed at a public working group meeting Nov. 19, said White.

Paul Merrill, the Maine Department of Transportation director of communications, said in an email that “the Mills administration is committed to a robust and transparent public process regarding the Port of Searsport.”

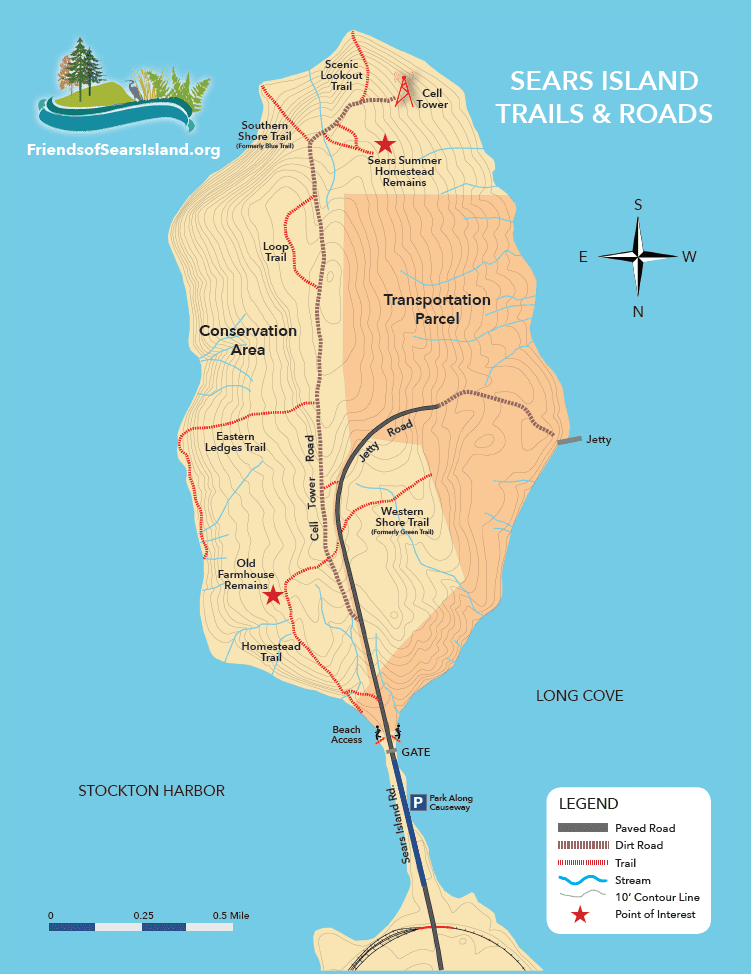

Sears Island, which lies just south of the port of Searsport and is connected by a causeway, is owned by the state of Maine. A large portion of the island — 601 of its roughly 936 acres — is under conservation easement with Maine Coast Heritage Trust. Friends of Sears Island (FOSI) is the land management entity for the conserved land. The Maine Department of Transportation (MDOT) maintains the parcel on the western side of the island where the facility would be built.

FOSI was first notified on Nov. 11, and the group’s leadership was briefed on Nov. 15 and 17, Merrill wrote. The study was released Nov. 23.

“MaineDOT is now organizing its public engagement and communication process regarding the Port of Searsport, which will include assembling a stakeholder advisory committee that includes the FOSI. That committee is expected to start meeting early next year,” according to Merrill.

Ciona Ulbrich, senior project manager with Maine Coast Heritage Trust, said the organization was not involved in the planning process but was given “a courtesy heads-up not long before the public announcement,” which she described as “fully appropriate.”

“It’s not a requirement that we be given lots of warning,” Ulbrich said, “but what will be important is for us to be involved in the planning and development from now on.”

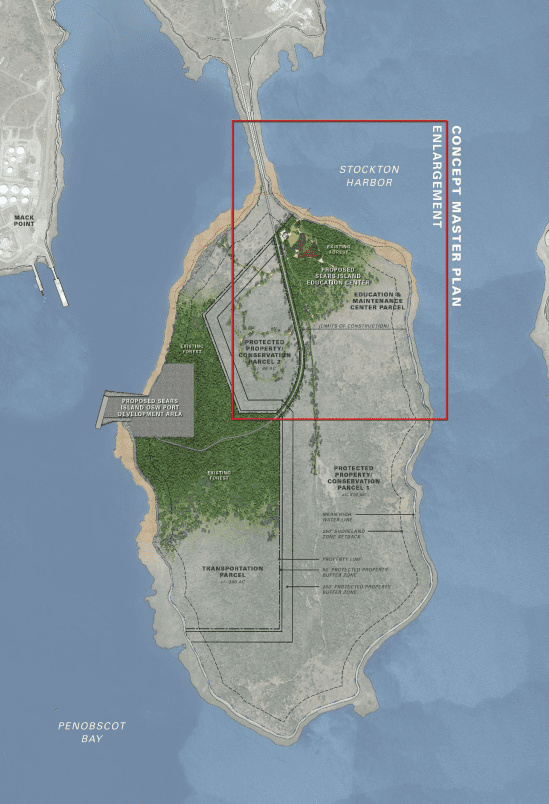

Moffat & Nichol, the firm that conducted the state-commissioned study, considered several sites in addition to Sears Island, including Mack Point, which currently operates as a liquid and dry bulk cargo terminal. Mack Point is on the mainland, directly across from Sears Island. A press release in March 2020 announcing the commissioning of the report specified Mack Point but made no mention of Sears Island.

Board members and volunteers for Friends of Sears Island were shocked upon being told that while Mack Point was feasible, Sears Island had come back as the preferred site for the offshore wind proposal. The nonprofit isn’t against wind energy, said White, but is skeptical that the island, one of the largest bridged, undeveloped islands on the east coast, is the most appropriate place for the facility.

An industrial facility handling and assembling 800-foot-tall wind turbines would fundamentally change the experience of visitors, and disrupt the island’s ecology and wildlife, said White and the FOSI vice president, Rolf Olsen. Mack Point, they noted, already has industrial infrastructure.

Over the past few years, state agencies have invested in heavy bulk cargo handling equipment and upgrading rail infrastructure at the port facility in Searsport. It has already been used to bring in components for other land-based wind energy projects.

Big difference in costs

The U.S. Department Of Energy also has suggested using the Mack Point terminal as a possibility to fabricate the foundation and assemble the Aqua Ventus turbine, an 11-megawatt floating demonstration project that will eventually be deployed south of Monhegan and connected to the mainland by an underwater cable. That project, which would be the first floating offshore wind demonstration in North America, is in the permit stages.

“I continue to think Mack Point is a better alternative. It is more costly but it can be done there. It is feasible,” said Olsen. “It’s just more expensive.”

It would be quite a bit more expensive, according to a preliminary estimate drawn up by Moffat & Nichol. A two-phase facility on Mack Point capable of handling a full-scale, 1-gigawatt commercial project would cost $450.6 million to construct — or $166.7 million more than one on Sears Island.

Those buildout costs likely would be borne by “a combination of federal, state and private funds,” said Tony Ronzio, the Governor’s Energy Office spokesman, in an email, although it’s still too early to tell. Once built, it’s possible the facility would be owned by the state and leased to a company that would manage it and run operations.

While construction of any facility will be costly, there’s also a lot of money to be made by both state and commercial interests. With the recent announcement by the Biden administration of federal targets of 30 gigawatts of offshore wind energy by 2030, the market is expected to grow rapidly in the coming years.

The 11-megawatt Aqua Ventus turbine is expected to cost $100 million to build. A 1-gigawatt (1,000-megawatt) project consisting of several hundred turbines would cost around $4 billion, said Dr. Habib Dagher, a working group member and wind energy expert, during a meeting last month. Roughly $1 billion would go to making foundations, and another $500 million would be for putting them in the water. Those are areas Maine and developers could capitalize on.

But cost is not the only reason Sears Island was preferred.

Although buildout there would likely take longer — six years, compared to four years at Mack Point — the island has greater possibilities for expansion, lower remediation costs, better access to deep water, soils available for fill and fewer existing commercial infrastructure or utilities than Mack Point, according to Moffat & Nichol. Mack Point might also require dredging, a lengthy and controversial process, while Sears Island likely would not.

‘We’re going to lose a lot of visitors’

Communities in Maine and across the world are bumping up against the challenges of siting energy infrastructure in previously undeveloped and under-developed areas.

It’s too early to tell how a facility of this size on Sears Island would change the visitor experience, said Ulbrich of Maine Coast Heritage Trust. “It always depends on scale, location, details.”

“It is a challenging issue for us in trying to balance conservation, and the obvious needs around alternative energy and other pressures of climate change,” she added. “There’s no clear or perfect answer.”

The Moffat & Nichol report includes possible conservation “improvements,” such as an education center and parking lots on the conserved parcel. Although FOSI representatives had informal discussions with an MDOT liaison in the past about an education center, the group was not consulted or told it would be included in the study.

“We’re not convinced that’s something that should be done,” said Olsen. “A lot of people just want to keep that quadrant of the island preserved and completely undeveloped.”

White and Olsen argued that for Sears Island, the benefits of having an easily accessible island for public recreation free of commercial infrastructure outweigh the higher price tag of building at Mack Point. It also helps keep people and their impact away from areas that may be even more ecologically sensitive, such as bird nesting islands.

“I’ve tried to envision, you know, an actively used trail network and beach area, recreation area coexisting with an active port with trucks, big trucks running up and down the road and across the causeway,” said Olsen. “It’s been very difficult for me to envision that as a successful coexistence.”

FOSI has kept track of traffic to the island from early June and late August for the past three years. It counted 16,843 vehicles coming to the island this summer, a 19% increase since 2019, said Olsen, noting that visitors enjoy the island year-round.

“Nobody will want to walk around there with all of the noise, the industrial use,” White said. While the trails are not ADA-accessible, many residents enjoy walking on the paved road that runs down the middle of the island, which might no longer be possible with the proposed development, she said. “I think we’re going to lose a lot of visitors.”

State wants to move quickly

Plans for Sears Island are in the early stages, but state officials would like to move quickly, in part to give Maine an edge in the emerging floating offshore wind market.

During a meeting in early December, working group co-chair Matt Burns of MDOT said the intention is to begin preliminary design and further studies for facilities on Sears Island as soon as possible while simultaneously conducting stakeholder outreach. Ideally, he said, construction would start by 2024.

“I don’t know how realistic that is at this point,” said Burns. “This is going to be a really intense public process.”

Several working group members pointed out that the conservation process for Sears Island had been controversial and it was important to involve the public early on.

Some wondered about public awareness of the group’s deliberations until this point. The working group meetings, typically held biweekly on Friday mornings, are broadcast on Zoom but not recorded.

Public comment is taken at the meetings, but over several months there have been few commenters outside of those in the industry. A viewer who asked to record an early meeting was told the group preferred meetings not be recorded. Meeting summaries and materials are posted on the state’s website, as are agendas and sign-ups for future meetings. Meetings of the larger advisory group are recorded and posted on YouTube.

Neither White nor Olsen were aware of the working groups or the meetings until The Maine Monitor mentioned them.

“These people’s neighborhoods are going to take a lot of heavy trucks, there’s going to be a lot more activity in local areas and that might cause some fear,” said Grant Provost, business agent for Ironworkers Local 7, during the December meeting. “We just don’t want it to seem like it’s getting forced down the public’s throat.”

Burns said in the December meeting that there had been “several meetings with stakeholders already” and the working group was trying to be “as transparent as possible.”

MDOT representatives, including Commissioner Bruce Van Note, have met with the Searsport Select Board, and Town Manager James Gillway attended at least one working group meeting.

Representatives presented the plans to the select board at a Nov. 30 workshop. Although board workshops are open to the public and some are listed on the town website, the Nov. 30 workshop is not listed. Olsen was invited to the meeting and said select board members asked good questions, but no public comment was taken and FOSI was not given the chance to speak.

Environmental issues apparent

Although the state wants to move quickly, environmental issues that could hold up permitting are already apparent.

“There’s definitely some red flags or things that would be difficult, as far as visual impacts,” said Jessica Damon, who works with the Maine Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) on wind projects, at the December working group meeting.

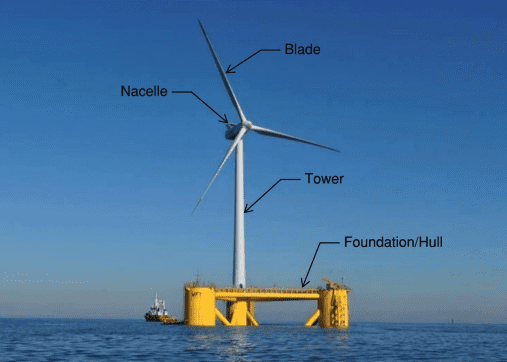

Damon thought there were likely to be issues with the amount of fill being moved and the height of the turbines. Normal site permitting requires that the project fit “harmoniously into the environment,” which “would be very challenging,” given how tall turbines are when assembled, she said. Rising between 700 and 800 feet from waterline to blade tip, the machines will rival some of the nation’s tallest buildings.

It would have been difficult to permit wind turbines on land if the state hadn’t tweaked the visual impact requirements with the Maine Wind Energy Act, Damon said. “Maybe we can do some changes beforehand to be able to permit these.”

Even if construction started tomorrow, workers likely wouldn’t be able to build enough floating turbines for the state to meet its goal of having 5,000 megawatts of offshore wind installed in the Gulf of Maine by 2030, Moffat & Nichol concluded.

That would require up to 500 turbines, depending on how much power each generates. A manufacturer would have to work continuously for years to build that many, and considering there are no commercial producers of floating‐bases in the U.S., the authors pointed out, “a more realistic goal would be to have a single large commercial installation (400 – 1,000 (megawatt) e.g.), in operation by 2030.”

Searsport emerging as hub

Whether or not the facility is built on Sears Island, Searsport has emerged as the state’s likely hub for offshore wind manufacturing and assembly because of its centralized location, deep water, and access to rail, highways and workforce. Eastport and Portland will be involved as well, and further studies are underway to determine how they might support the industry in Maine.

Because offshore wind turbines and their foundations are so large, each component must be manufactured or assembled close to the water, with no bridges or electrical wires overhead and water deep enough to accommodate the ships to tow them out to sea. There are few ports (and few ships) that can handle such enormous parts, and there are no ports designed specifically for floating offshore wind anywhere in the world, according to Moffat & Nichol.

Floating offshore wind is exactly what it sounds like: Rather than being fixed to the sea floor, the foundations and turbines float on the surface, held by an anchorage system. The turbines can be sited in water depths of greater than 200 feet, where fixed bottom foundations are costly and inefficient.

There are no commercial scale floating offshore wind projects anywhere in the world, according to Moffat & Nichol, although a number of demonstration projects are underway. Aqua Ventus is the only project in North America. Maine also recently filed an application to open a floating research array area that would support a demonstration project of up to 12 floating turbines.

During working group meetings over the past few months, experts made clear that manufacturing, assembling and deploying floating wind turbines is where Maine could make its mark on the offshore wind industry.

“The opportunity in Maine is to lead in floating (offshore wind),” said Dagher, the working group member.

Disclosure: Kate Cough’s husband, Caleb Jackson, works with Maine Coast Heritage Trust and is involved in overseeing the conservation easement on Sears Island.