In the days before William McIver ended his life, he told a few of his friends he was thinking about suicide.

His classmates at Woodland Junior-Senior High School thought they had convinced the 14-year-old not to carry out his plan.

In the middle of the night on Jan. 27 William killed himself in his bedroom. His death – the fourth suicide in two months in the northeastern region of Washington County – devastated his family, his school and his community.

The tragedy also highlighted the need for suicide awareness and prevention in the schools and small towns of this sparsely populated county bordering New Brunswick.

“As a school we didn’t recognize the signs and we didn’t have a system for the kids to communicate the signs to us,” said Janice Rice, guidance counselor for Baileyville schools. “We need to let these kids know they can come to a teacher or another adult in the community. They shouldn’t have to carry this burden alone.”

In a county where there are only three traffic lights, two cities and 31,500 people, word spread quickly about William’s death. Conversations in local shops, gas stations and grocery stores centered around the four suicides that began in early December and ended in late January. Three were men under 40. Two were veterans. The community grieved for the families who had lost their sons, and they worried about others struggling with depression or despair.

“People don’t understand that Washington County is one big community,” explained Mary Anne Spearin, principal of Calais Junior/High School. “Everybody knows everybody. One suicide is too many, but to have four in the last few months – it was just overwhelming.”

Spearin and Marcia Rogers, a longtime advocate for Washington County’s youth, knew it was vital for the community to talk about suicide prevention.

“I knew three of the four who died (by suicide),” explained Rogers, the manager of the Calais Head Start program and a Calais city councilor. “People often say there are no signs, but I think the signs are there, and we either don’t see them or we don’t know what to do with them.”

RELATED: The crushing toll of a pandemic in Maine’s ‘forgotten county’

Ten days after William’s death, Rogers, Spearin and 90 members of the community joined a Zoom forum led by Greg Marley, suicide prevention director for Maine’s chapter of the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI). Marley welcomed the large turnout of parents, teachers and counselors.

“Suicide prevention,” Marley explained, “is up to all of us. Not just mental health clinicians or school counselors but everybody.”

For over 20 years, Marley has educated communities and schools throughout Maine on suicide prevention and awareness. He also helps schools in the aftermath of a suicide.

“More than anything else, early on it’s important to be able to establish a clean communication of what happened and to make a very careful assessment of who is most impacted by the loss, both students and staff,” Marley said. “And to triage outreach and support.”

Maine children, according to a 2019 Journal of American Medical Association Pediatrics study, have one of the highest rates of mental illness in the nation. About 1 in 4 children in the state has at least one mental health disorder, like depression, anxiety or ADHD.

Marley believes that figure doubled this past winter.

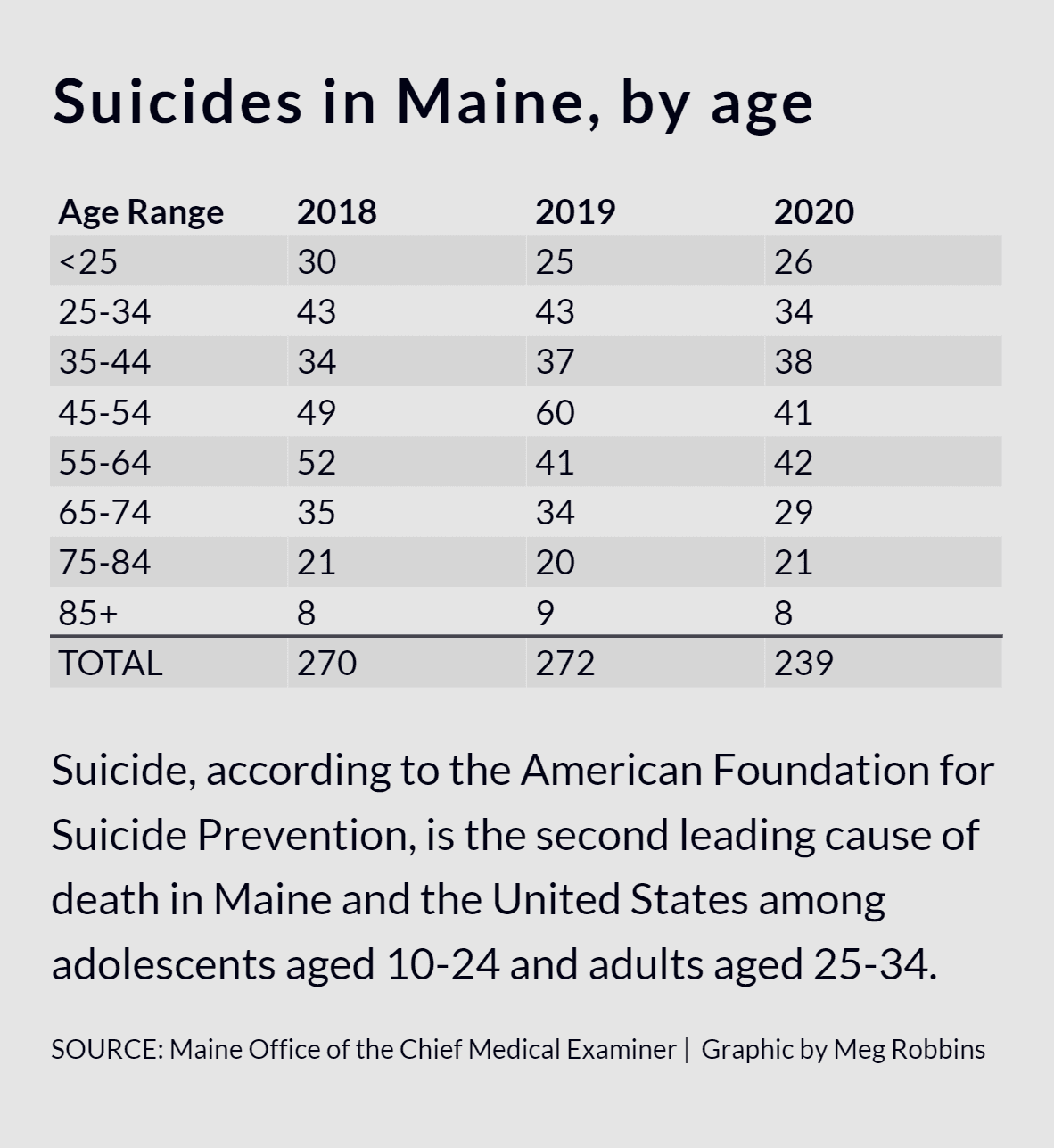

“During the first six months of shutdown, people were white-knuckling it and holding on,” Marley said. “Through late fall and winter there have been an increase in crisis calls, and we’re hearing about a lot more suicide attempts and suicidal ideation as well as completed suicides in the state.”

At Calais Middle/High School, Spearin and her staff grew concerned about students slipping into depression or having suicidal thoughts.

“There is definitely an increase of students seeking help or students we know are at risk,” Spearin said. “They’re communicating that they have those challenges, and I’m not sure that hopelessness is the word for it, but just a sense of being alone.”

During the Feb. 10 forum, several parents said they were unsure of what signs to look for and where to get help if they knew someone was suicidal.

“We’ve got to make the community more aware of what are the signs and symptoms,” Spearin said. “What are the things you can do to respond and who do you reach out to?”

RELATED: Alone with the grief, alone with the pain

Yet, in a county with one psychiatrist, one pediatrician and few mental health resources, finding help is challenging, Spearin said. Frustrated with long waiting lists and few crisis beds, the forum’s participants agreed to create a NAMI affiliate in Washington County. Run by trained volunteers who often have lost family members to suicide, NAMI Maine’s seven existing affiliates help find resources and offer peer support.

Nancy Audet, NAMI Maine’s director of community engagement, was heartened by the number of Washington County parents, educators and leaders who want to start a local affiliate.

“I left the meeting with a list of people who want to run support groups and programs that help families with mental health challenges,” Audet said. “By summer, we hope to have people in Washington County trained and ready to go.”

Inside the county’s schools, principals and guidance counselors are also requesting more in-person training for students and staff. Though teachers are required to have one-to-two-hour suicide prevention education every five years, it is often a virtual session that does not include discussions.

“The gold standard,” Marley said, “is to have face-to-face training with a question-and-answer session and conversations about specific protocol for a particular school district.”

Baileyville guidance counselor Rice is eager to receive NAMI training and set up more in-depth suicide prevention workshops for her district’s teachers. With NAMI’s help, she also plans to develop courses for students.

“We’ve got to do better,” Rice said. “Our kids have to have more information. They have got to know what to do if someone is talking about ending their life.”

Though she understands there may be concern over teaching a subject that has long been taboo, Rice believes suicide education should be required.

“From Pre-K to grades 12 we teach about inappropriate touching,” Rice said. “So why not talk about suicide?”

It is also important, Rice added, for families to share concerns about a student’s mental health with a guidance counselor or school nurse. Rice did not know that William had tried to end his life while he was in middle school.

“I didn’t know about his first attempt,” Rice said. “No adult at school knew about his struggles. We need to let parents know that they should tell us about these important details.”

Victoria Siering had known William McIver since kindergarten. He talked to her about his first suicide attempt and promised he would not try again. But Siering also knew William hid his feelings and “often smiled through the pain.”

Some of her classmates at Woodland Junior-Senior High are still struggling with the loss of a boy who died too soon, and the 14-year-old girl wants them to know it’s OK to talk about feeling sad, depressed or anxious.

Siering created 300 key chain bracelets with the words: Your Life Matters. She placed the keychain, Life Savers candy and a card with the Maine Crisis Hotline phone number into plastic bags. She handed them out in the school halls, the cafeteria and in classrooms.

“I feel like the key chain will remind kids that if they need someone to talk to, there is always someone there for them,” Siering said. “That they’re not alone.”

Siering also plans to set up a suicide prevention walk in the fall to honor her classmate and to continue spreading the message that there is always hope.

“William was a very caring person,” Siering said, “He was always putting his feelings aside to help other people. He would want us to help each other.”