I’m writing this on Thursday with the horrific news out of Lewiston still looming large. There are so few words that can offer comfort at a moment like this, and yet it feels wrong and pointless to talk about anything else. So I want to start today with a pause. To my fellow Mainers, I am sending love, solidarity and hope for change. I offer you this space to take a deep breath and give someone a hug.

My husband Nick and I are incredibly lucky to be in the process right now of buying our first home. We’ll move next week from our apartment in Portland’s West End to an old house (c. 1900) on the Megunticook River in Camden.

The house is in pretty good shape for its age — as I’ve written here previously, we’ve lived in worse — but it will still give us lots of opportunities to be the change we want to see in the warming world by investing what we can in electrification and energy efficiency upgrades.

On Wednesday, we began that process by getting a home energy audit.

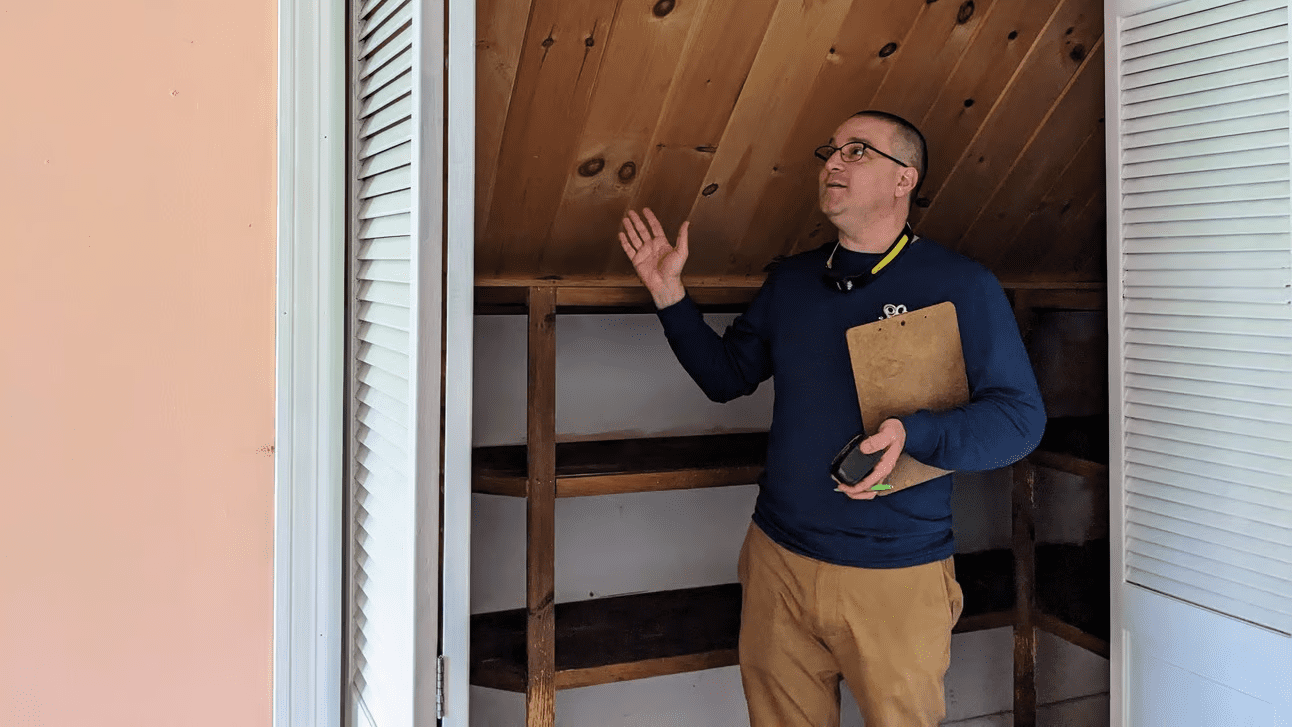

Our auditor was Colin McCullough of All-Around Home Performance, based near Gardiner. McCullough spent years working for Efficiency Maine and its Massachusetts analog, MassSaves, before starting his business. He also works with the Maine chapter of the Building Performance Association.

McCullough’s pitch for getting a home energy audit is simple: It’s an easy, quick way to find out where to seal up air leaks and insulate your house, to create only the right amount of ventilation for health and comfort and to get the most for your money on home heating, cooling and pricey upgrades to those systems.

Home heating is a huge contributor to Maine’s emissions and a major economic burden on many families. Using less energy is the first, simplest way to fix that — and an energy audit can show you the best paths to doing so.

Earlier this year, I sat in on an energy audit in Aroostook County for my series Hooked on Heating Oil with the Monitor and WBUR. Like the home in that story, our new place has an oil tank, forced hot air furnace and a wood stove.

Nick and I know we don’t want to use oil long-term, both for cost and environmental reasons. We’re interested in heat pumps, but we knew that the degree of weatherization in our house could make or break their affordability and efficiency. So the energy audit was an obvious first step on our journey.

“Especially if it’s an older house that doesn’t have much insulation and there’s a lot of air leaks, then that heat pump or whatever system you put in is going to have to work a lot harder,” said McCullough. “Whereas if you have that insulation and air sealing work done, either at the same time or first, then you can put in a smaller, more efficient heating system and it’s just going to make it work better.”

As an independent auditor, McCullough is not trying to sell any one technology or service. He said he provides a more holistic assessment. We paid him $300 for a few hours of his time, some great advice, a full report we’ll receive next week, and lots of photos and measurements we can share with future contractors.

Many contractors, especially insulation installers, according to McCullough, will offer a free or discounted audit as a precursor to a potential job. Here’s Efficiency Maine’s list of contractors that offer energy audits. I set this search to a 50-mile radius of Portland, but you can explore it for yourself.

Depending on your income, you can also seek a free energy audit from your local community action agency. And you can get a federal tax credit of up to $150, or 30% of your costs, for an inspection by an eligible auditor. For more information on home energy upgrade incentives, try the advocacy group Rewiring America’s Inflation Reduction Act benefit calculator, or check out parts one and two of my guide to moving off oil.

So what was the audit actually like? Simple, really. McCullough measured the square footage and volume of the house in detail, taking a tape measure to every wall, corner and window. He asked what we knew about the home heating systems and the roof, and their age. He took a lot of notes and pictures.

We spent a while in the basement, poking around behind weird plastic wall sheeting and in the drafty bulkhead doorway. He looked for signs of moisture build-up and suggested many upgrades we could run past an HVAC contractor. We repeated the process in the attic, where McCullough measured the insulation he could find in the walls and floor and told us its type, condition and usefulness.

He scrutinized the furnace and cranked up the heat to test its output. In the back of a closet, he drilled a small hole in an exterior wall to look at the depth of that insulation and found it was in pretty good shape, meaning the basement and attic should be our focus for tightening the home’s envelope.

We mused about whether adding a floor vent in front of the wood stove would help better circulate that warm air throughout the house. We talked about the type and number of heat pumps that would work best for our house, where to put them and what other work might need to be done first.

Then came the part I was most excited for: the blower door test or, as McCullough called it, the “red door of truth.” This depressurizes the house to simulate a strong wind blowing on the outside, making air leaks obvious to the touch or with a thermal imager.

You can see and hear one in action in my earlier heating oil-related story. Incidentally, that audit showed that some basic weatherization would save that homeowner $1,200 a year on his heating bills.

But at our house, there was a problem — our moisture issues had caused some mold in the attic and basement, which other tests have showed us is non-toxic and which we planned to address in the short-term. McCullough said the standard blower door test would pull those spores into the main living space.

So instead, he reversed the equipment to pressurize the house, as if the wind was inside. It didn’t give us the fun thermal visual of air leaking from our outlets and window seals, but it did measure the air moving through the house.

Compared to our square footage and volume, it showed that all the air in the house was changing over about 12 times per hour. McCullough said the most efficient standard, in the more efficient 2021 or “stretch” international building codes used by Portland and South Portland, is three cycles an hour.

All this makes it clear that even in an old house in pretty good shape, there’s a ton we can do to waste less of our heating and cooling, be more comfortable and save money. “I wish I could do an energy audit on every house in the state,” McCullough said — not to earn money, he said, but because it just helps.

We’ll talk to an HVAC contractor about insulation in the attic and basement and look into other changes McCullough recommended while we shop around for our first heat pump.

Stay tuned for many lessons to come, and be safe and well.