Editor’s Note: The following story first appeared in The Maine Monitor’s free environmental newsletter, Climate Monitor, that is delivered to inboxes for free every Friday morning. Sign up for the free newsletter to get more important environmental news from reporter Kate Cough by registering here.

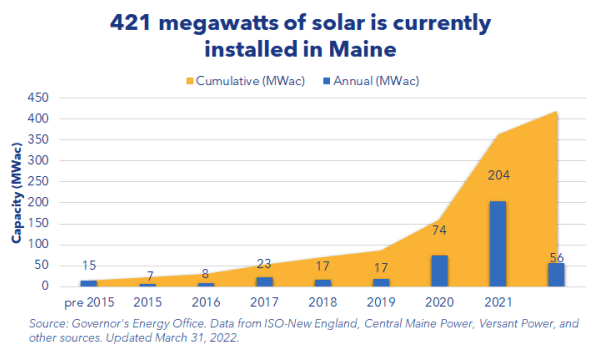

In the past few years I’ve run out of satisfactory descriptors for solar development in Maine. It’s booming. It’s soaring. It’s an explosion. A gold rush (my least favorite). Whatever you want to call it, the pace of development has shot steadily upward in the past five years. And it’s starting to have some unintended consequences, like farmers competing with developers for land, and large blocks of wildlife habitat — important for birds, bats, deer and lots of other critters — from being broken up.

That’s why staff at the Maine Department of Environmental Protection have begun crafting rules aimed at guiding solar projects away from certain places by rewarding developers who do so with a more streamlined permitting process, saving companies time and money.

“I can’t think of another type of development where all of a sudden you’ve seen such an increase,” Nick Livesay, director of the Bureau of Land Resources at the DEP, told the Board of Environmental Protection during a meeting on Thursday.

“We have hundreds of solar projects. We have not had hundreds of shopping malls, or hundreds of industrial facilities,” Livesay continued. “It’s been overwhelming for staff trying to process all of these permits.”

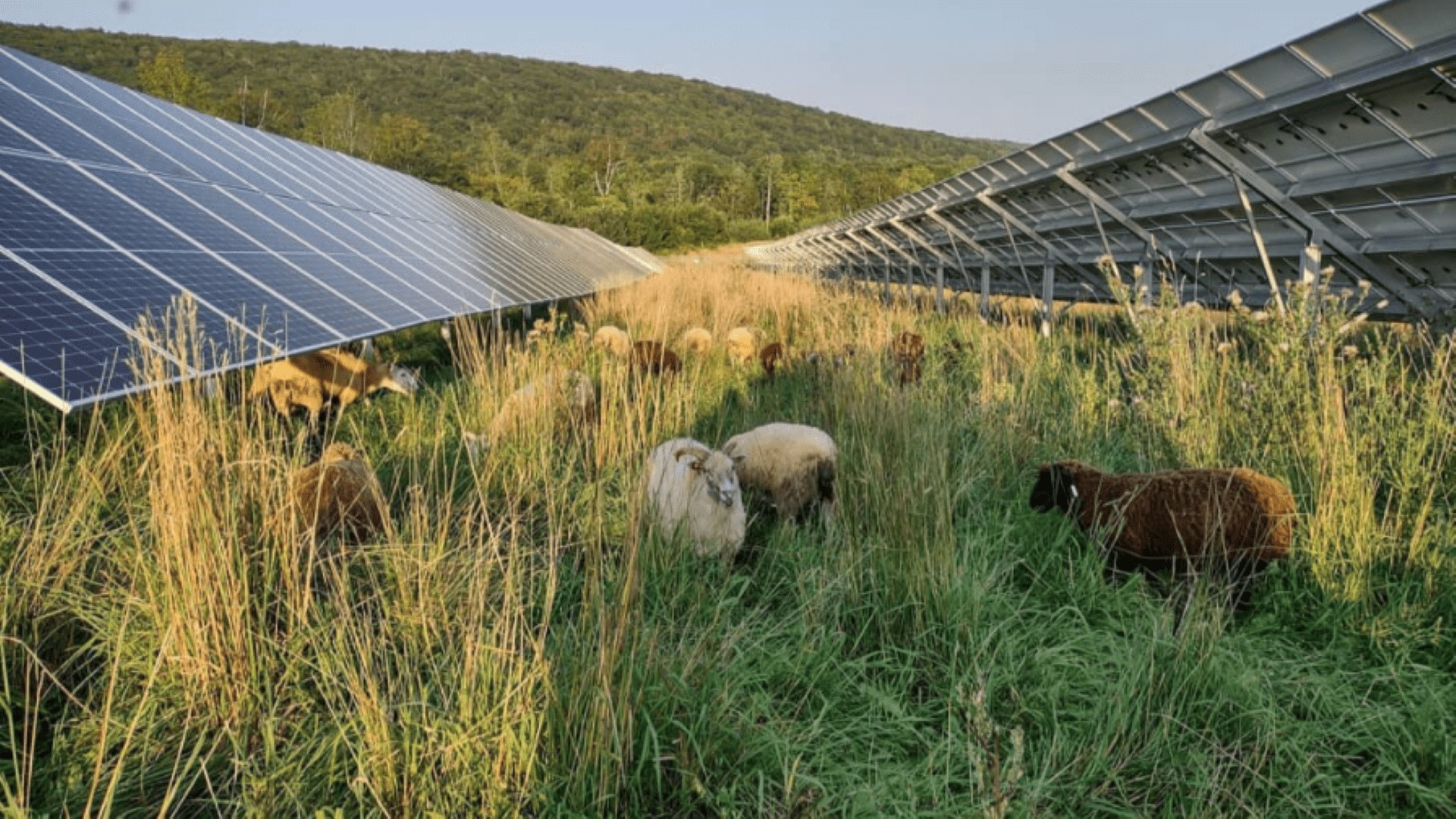

Solar arrays tend to be low-impact after construction, with few changes to traffic, noise or stormwater runoff. But they are unique in their large footprint and location patterns. Unlike shopping malls or industrial sites, which tend to be clustered near high density areas already impacted by humans, solar arrays can be located in rural areas that have previously seen little development, places that might be providing valuable living space for flora and fauna.

Those biodiverse ecosystems are also important for fighting climate change, said Naomi Kirk-Lawlor, a senior planner with the DEP. Swamps and wetlands, mucky though they may be, absorb carbon dioxide and provide a buffer against flooding and drought, mitigating some of the effects of climate change. But so far, said Livesay, the state hasn’t done a great job assessing the potential impact of so many solar arrays on large undeveloped habitat blocks.

“There’s a need to incentivize the siting of solar development away from those most valuable habitat blocks,” Kirk-Lawlor told the Board on Thursday.

Under the current rules, many developers are configuring projects in “non-optimal ways,” said Kirk-Lawlor, in order to stay below the threshold that triggers a Site Location of Development permit, a time-consuming and rigorous process. Those workarounds are “not a good outcome for meeting Maine’s renewable energy goals and getting the most efficient power generation from each solar development project,” she said.

The new rules, which are still being crafted, would allow solar developments between 20 and 50 acres that meet certain criteria to eligible for permit-by-rule, a much faster regulatory process reserved for projects that have “no significant impact on the environment” as determined by DEP, Kirk-Lawlor said Thursday.

Only projects located in certain areas would be eligible, said Kirk-Lawlor. To that end, DEP staff, with help from the Nature Conservancy, are drawing up a map of core habitat blocks (large undeveloped areas ranging in size from 250 to 500 acres) and connector areas between them, which Kirk-Lawlor described as “kind of like stepping stones” for animals to get from block to block.

For a developer to take advantage of the faster permitting process, no more than 25% of the project could be in core or connector habitat blocks, and none of it could encroach on “key bridge areas,” where animals are most likely to traverse. Solar projects would also still need review by other state agencies to ensure there’s no significant impact on threatened or endangered species or unusual natural areas. They would also have to meet a higher bar for erosion and sedimentation control.

The DEP does not have jurisdiction over agricultural land, said Livesay, but other state agencies are in the midst of figuring out how to optimally site solar while preserving Maine’s limited viable farmland.

These rules, if they’re eventually adopted, wouldn’t supercede or have any legal impact on municipalities, said Livesay, nor are they likely to impact how much solar development there is in the state. Staff expect to have a draft to the Board by September.

“I don’t think anything contemplated in this rule is going to attract more or less solar development in Maine,” said Livesay, but it might influence where it goes.

In many cases, projects are already organically locating in optimal areas, said Kirk-Lawlor. The goal, she added, is to “streamline permit approval for some projects while assuring that there’s no significant impact on the environment and incentivising the siting of solar development in the right places to protect valuable habitat blocks from fragmentation.” All that “can still be done while meeting the state’s renewable energy goals.”

To read the full edition of this newsletter, see Climate Monitor: DEP looks to streamline permitting process for certain solar developments.

Kate Cough covers climate change and the environment for The Maine Monitor. Reach her by email with ideas for other stories at gro.r1751756860otino1751756860menia1751756860meht@1751756860etak1751756860.