Maine’s major health systems ended 2020 in the red as they grappled with the costs of responding to the COVID-19 pandemic. Hospital leaders expect 2021 to be less dire but predicted the financial fallout could continue for years.

And at least one expert said the pandemic revealed that it’s time to rethink how hospitals are financed.

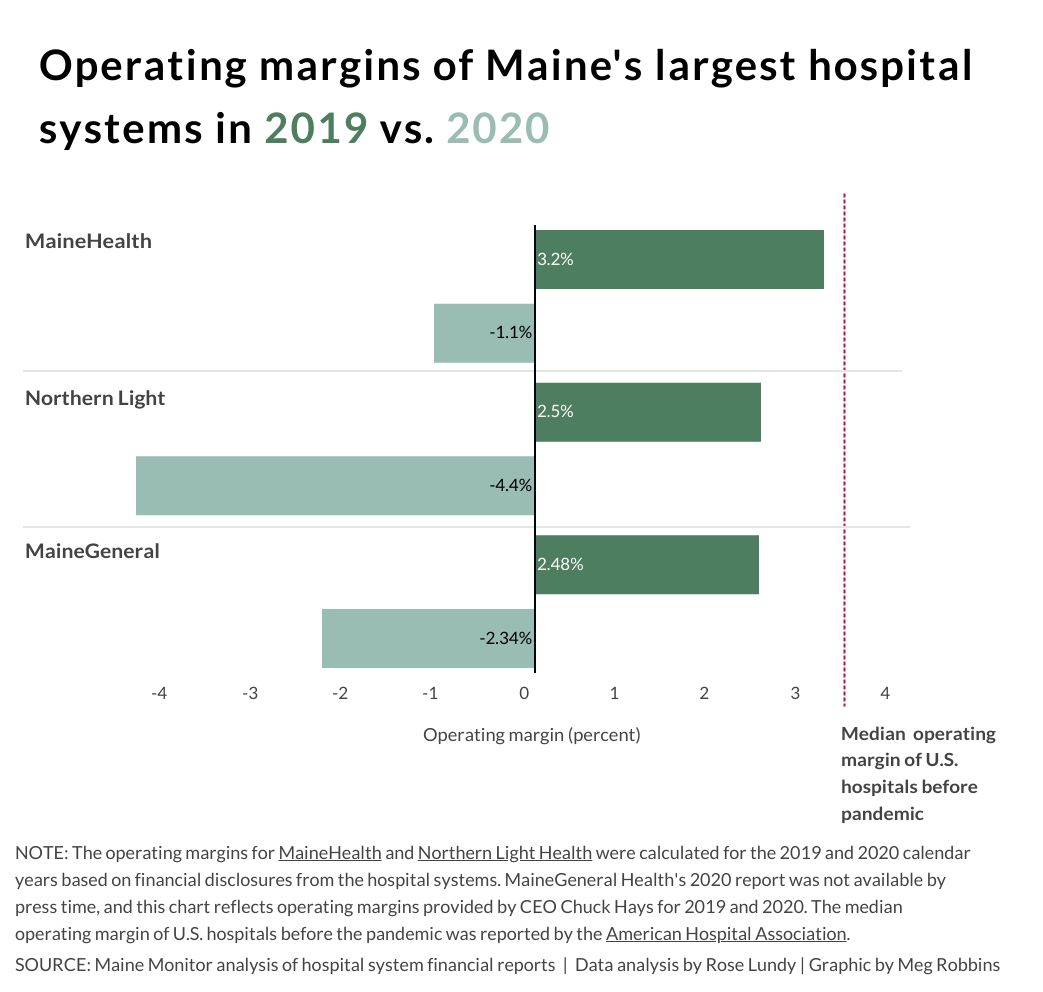

Portland-based MaineHealth, Bangor-based Northern Light Health and Augusta-based MaineGeneral ended 2020 with negative operating margins, indicating that expenses were higher than revenue, according to financial disclosure documents released earlier this year. All three ended 2019 with positive operating margins.

Experts and hospital leaders cited a number of reasons for the financial strain during 2020. When the coronavirus began to spread across the U.S., Maine paused non-emergency services, cutting off a major source of revenue for hospitals. Even after these services reopened, patients were hesitant to seek medical care during a public health crisis. Hospital leaders said patients are starting to come back, but not at the levels seen before the pandemic that killed more than 790 Mainers.

At the same time hospitals and health facilities were losing revenue, they also faced increased costs of protective equipment, safety measures, longer stays for COVID-19 patients, and additional staff to help with screening, safety gear and shift coverage when employees had to quarantine.

Steven Michaud, president of the Maine Hospital Association, said the pandemic would have been “devastating” to the state’s health system without the CARES Act passed by Congress last spring, which allocated $178 billion for providers across the country. Maine so far has received about $653 million.

“The difference it made was life and death. It cannot be overstated,” Michaud said. “We were looking at losing several hospitals, lots and lots of layoffs, service reductions.”

Representatives of health systems in Maine agreed that the funding was a lifeline but said it was not enough to fully address the costs of the pandemic. Even after the federal bailout, Michaud said Maine hospitals have lost at least $300 million in total since the start of the pandemic.

MaineHealth, the state’s largest health network with 11 hospitals, projects a total net loss of $175 million from November 2019 to September 2021. That’s equal to more than two years of revenue after expenses, Chief Financial Officer Al Swallow said. And the losses could have been double that if MaineHealth hadn’t received $205 million in assistance from the federal government.

“We’ve benefited from the federal programs by more than half our losses, but the losses are still substantial,” Swallow said.

MaineHealth ended 2020 with an operating margin of -1.1 percent, according to financial statements. In 2019 the margin was 3.2 percent.

Swallow said MaineHealth could end 2021 in a better place than the prior year, but still might not return to a normal year and wouldn’t make up for the lost revenues of 2020.

MaineHealth, along with other systems, has the added expense this year of standing up vaccine clinics across the state. The vaccine is paid for by the federal government and health care providers receive some funding for its administration, but Swallow said it’s not enough to cover the investments MaineHealth made in the facilities and the staff to run them.

On a ‘razor-thin’ edge

Hospitals across the country are experiencing the same financial crunch and could end 2021 in a similar situation.

Before the pandemic, about one in four hospitals had negative margins, according to a March 2021 study from KaufmanHall prepared for the American Hospital Association. At the start of this year, that increased to include half of hospitals in the U.S. Under the most optimistic scenario, KaufmanHall projected that 39 percent of hospitals will end 2021 with a negative margin — significantly higher than before the pandemic. Under the worst scenario, almost half of hospitals could end the year with negative margins.

That’s “really very concerning,” said Aaron Wesolowski, American Hospital Association vice president of policy research, analytics and strategy. Any business or organization needs to bring in more money than it spends to continue operating, investing in new technology and keeping pace in the labor market, he said.

Maine hospitals were on the edge before the pandemic. Nearly half of them ended 2019 with a negative operating margin. The average margin was 1.4 percent, which Wesolowski called “razor thin.”

“What may look like a slight dip (from a positive to a negative margin) can be really very, very challenging to manage, especially when where you’re dipping from is a very slim margin,” Wesolowski said.

Michaud said it’s too early to know how all hospitals in Maine ended the year financially.

Wesolowski said it’s difficult to predict how long we could be in this financial crunch. The projected losses for American hospitals in 2021 could be between $53 billion and $122 billion, which is 4 to 10 percent of total revenue. The vaccine rollout could improve prospects, but states relaxing social-distancing rules could face more outbreaks, he said.

“Coming into 2021, we haven’t seen things go back exactly to baseline,” Wesolowski said. “Obviously we started off the year in January and February with another massive surge. A lot of the same factors that came into play in 2020 were very much present at the beginning of the year in 2021.”

Meanwhile, some of the wealthiest hospitals and health systems in the U.S. accepted significant federal bailouts and ended 2020 with hundreds of millions of dollars in surplus, according to Kaiser Health News and the Washington Post. Some hospitals returned federal funds, but most held onto the extra for anticipated pandemic costs, KHN and the Post reported.

Large hospital chains likely had “enormous” losses and therefore deserved large bailouts, said Michaud, with the Maine Hospital Association. But if those chains received a financial windfall and ended the year with large surpluses, “That’s a big problem. I have no problem saying that’s frustrating. Nobody should have made out like that.”

Northern Light Health, the state’s second-largest system, saw its operating margin drop from 2.5 percent in 2019 to -4.4 percent in 2020, according to financial documents. The system received about $88 million from the CARES Act provider relief fund through September 2020.

“The pandemic was like nothing we’ve experienced before, and our response will continue for the foreseeable future as we maintain testing sites, care for COVID-19 patients and vaccinate our communities,” a Northern Light spokesperson said in a statement. “Given this, the ways in which COVID-19 affects us financially and what the future looks like are still evolving. While federal assistance will most likely not cover all of our expenses, we appreciate any assistance to help offset the cost of responding to the pandemic.”

MaineGeneral Health ended 2020 with a -2.34 percent margin after ending 2019 with a 2.48 percent margin, according to its president and CEO, Chuck Hays. Financial documents through the end of 2020 are not yet publicly available.

Hays said the $33 million MaineGeneral received from the federal government was helpful, but without additional financial support or a turn in the pandemic, the health system may need to consider reducing services to stay in business.

“I think if the hesitancy (to seek care) stops, it would turn around fairly quickly,” Hays said. “It’s all about how comfortable people are and where the pandemic is. I think that’s going to be the driving force.”

Michaud said hospitals statewide have seen patient volume return essentially to normal, but predicted more minor costs related to protective equipment and other safety measures could continue for some time.

Lewiston-based Central Maine Healthcare, a fourth major health system in Maine, doesn’t have reports available that represent the full 2020 calendar year. John Whitlock, chief financial officer and treasurer, said he expects 2021 to still be “a struggle.” He’d like to see the accelerated payments from Medicare and Medicaid converted into grants instead of loans that need to be repaid.

“It was great to have when it came,” he said of the loans, “but I think this pandemic lasted a whole lot longer than what folks had expected.”

Rethinking how to finance hospitals

Rural hospitals could have the hardest time recovering because they depend on patient volume to sustain their business, according to John Gale, a senior research associate at the University of Southern Maine and the president of the National Rural Health Association.

When patients stopped coming in during the pandemic, small hospitals that weren’t part of a larger network didn’t have a way to make up the difference.

Though no Maine hospitals closed last year, 20 rural hospitals shuttered across the country, according to the University of North Carolina Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research. That’s the highest number since the center started tracking in 2005.

“Many were at high risk for closure prior to COVID, and I suspect they’re even at greater risk now because they don’t have the foundation and the resources to weather these big changes in utilization and related revenue,” Gale said. “It’s a big concern, and it has a large amount to do with how we pay them.”

It’s time to rethink how we pay for health care by lessening the dependence on patient volume for revenue, and increasing the services that are reimbursed by insurance and Medicare and Medicaid, he said.

When a rural hospital doesn’t get enough patients to pay for its operations, the local community may need to think about financing it together to keep the doors open, Gale said. Publicly owned facilities are common in the Midwest, he said, but most Maine hospitals are nonprofits.

Michaud said the topic is worthy of discussion but warned against “flip(ping) everything on its head because of a once-in-100-year pandemic.”

A set payment system for a hospital could work “in theory,” he said, but he has yet to see a successful one in practice.

But the pandemic “unearthed weaknesses in our health system’s foundations,” according to Gale, and it may take a variety of solutions to address them.

“I think it’s a combination of factors: No one solution is going to make these hospitals sustainable in the long run,” he said.