Weather disasters inflicted $145 billion in damages in the U.S. last year. The Northeast escaped largely unscathed, but that could change at any moment. More than 40 percent of Americans live in counties hit by climate-driven disasters, a number certain to rise as these events strike more frequently and forcefully.

Disasters start and end locally, emergency managers say, meaning that communities are the first to confront a crisis and are the ones left to rebuild long after outside help ends. That adage underscores the cyclical nature of disaster management, which involves taking mitigation measures to reduce future risks, preparing to protect lives and property, responding to events, and — while still recovering — resuming work to further limit risks. Through every facet of this cycle, emergency managers offer coordination and support.

Local government is the most important level for integrating mitigation and climate planning, observed Anne Fuchs, director of mitigation, planning and recovery at Maine Emergency Management Agency (MEMA), “but that’s the level that tends to be most resource strapped. Unfortunately, funding deficits and lack of capacity have kept many Maine communities from effectively planning for and preparing for disasters.”

A call for ‘disaster justice’

“Disasters are not freak accidents, they are the inevitable product of the decisions we, or some people, make,” Samantha Montano writes in “Disasterology: Dispatches from the Frontlines of the Climate Crisis,” a compelling new book recounting her disaster recovery work and research in settings from the Gulf Coast to Camp Ellis, Maine (she grew up in Saco). It’s a damning portrait of a broken system, marked by inefficiencies, opportunism and blatant inequality — with resources often doled out along racial and class lines.

Montano warns that the nation’s emergency management system “will become constantly overwhelmed” in the face of intensifying climate disasters unless it undergoes radical change. “We know how to manage disasters more effectively, efficiently and justly,” she writes. “The challenge now is finding the courage and political will to make the changes we know are needed.”

Maine has relatively low risk compared to more disaster-prone states, Montano told me recently, and “relatively high social capital” — a strong sense of community that can help people mobilize effectively and provide “mutual aid” even without formal agreements.

But the state needs to invest more in reducing future exposure. “The more we do to mitigate our risk,” she writes, “…the less pressure we will put on our response and recovery system.” One obvious way to do that is for towns and cities to direct new construction away from high-risk areas – amending zoning laws, building codes and land-use policies. Put simply, Montano said, “they’re going to have to start saying ‘no.’ ”

Such measures do more than “save lives, minimize physical injuries, and lessen disaster-related mental illness,” in her words; every dollar spent on mitigation saves between $4 and $13 in response and recovery.

Preparedness takes a village

Efforts to reduce risk and prepare for disasters are often hampered by lack of local coordination and communication. Planning board members may assess long-term climate risks while emergency managers, many of whom juggle multiple jobs, focus on short-term public safety. Social service agencies, busy meeting urgent needs, may not take time to consider future scenarios.

What’s needed is a “whole community approach,” in Fuchs’ words, which brings together representatives and resources from private and nonprofit sectors, the general public, tribal partners and all levels of government. The Maine Climate Council, she said, “set up a really good platform to connect.” In Montano’s view, that process helped put Maine “ahead of most other states in integrating emergency management into climate planning.”

More community conversations are starting to happen through tabletop exercises, facilitated dialogues in which diverse organizational representatives discuss potential responses to a disaster scenario. Emily Kaster, deputy director of the Cumberland County EMA, said her agency now convenes these discussions fairly often. They’re “where the rubber meets the road, where we build the relationships and build the muscle memory” to make disaster responses more seamless.

Focusing on the most vulnerable

In tabletop exercises held this past week, as part of a five-year Social Resilience Project, roughly 50 people from eight communities in the Bath-Brunswick area talked over how best to prepare, respond and recover from a hypothetical disaster while supporting the region’s most vulnerable residents.

“Climate change is insidious,” Montano writes, “because it intertwines itself with our existing vulnerabilities and amplifies them.” Using tools like The Nature Conservancy’s online “coastal risk explorer,” this project is identifying the needs of residents who are older, homeless, lack vehicles, have language barriers or live in settings where flooding could close off road access and emergency services. Participants are developing a briefing book to share with other communities interested in scenario planning focused on vulnerable populations.

Attention often goes to shoring up hard infrastructure, said Ruth Indrick, project manager at Kennebec Estuary Land Trust, which has helped organize this effort, without necessarily “thinking about the connections needed between people to make communities more resilient.”

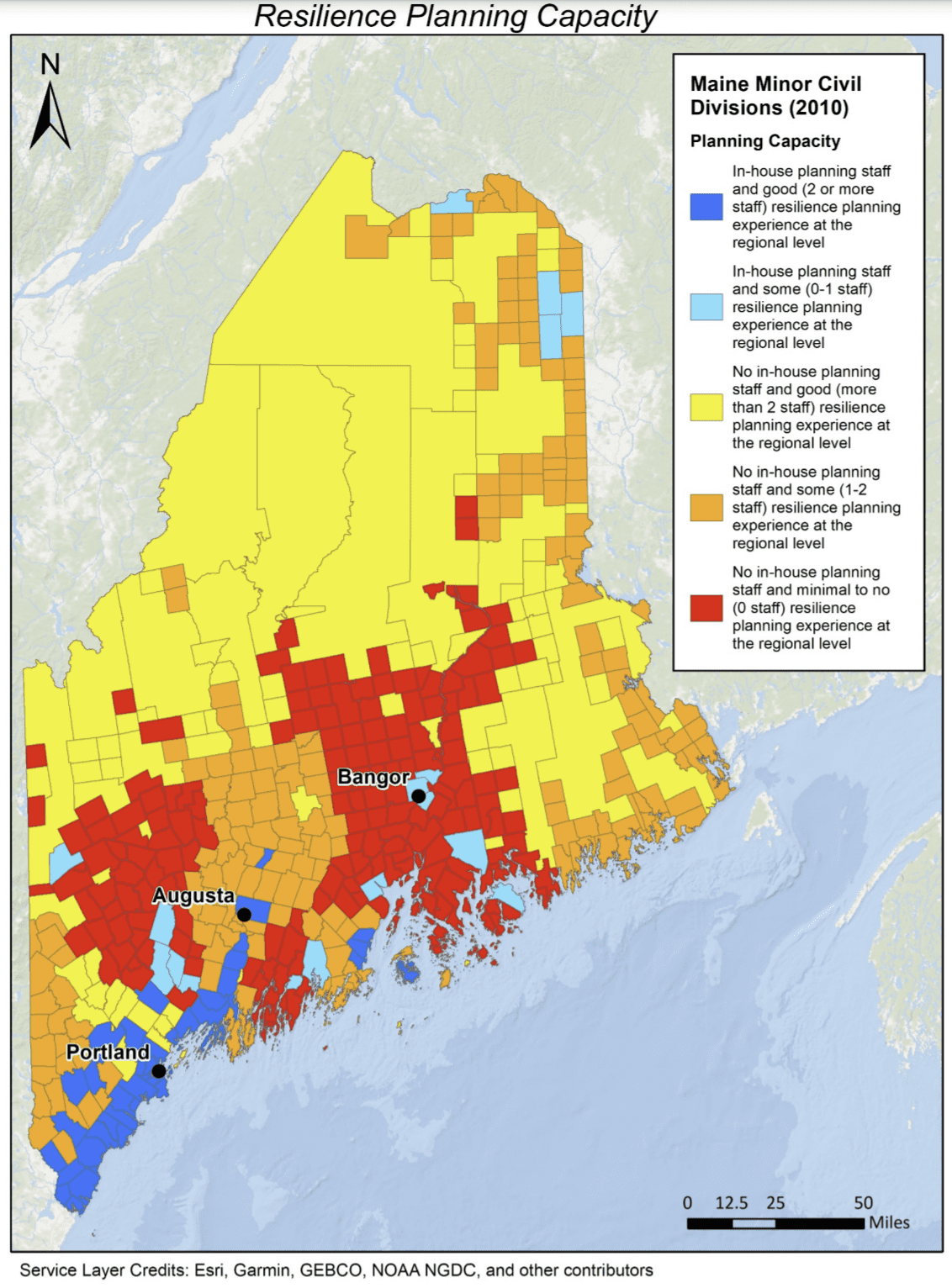

Guidance from projects like this one can help in areas with a high proportion of vulnerable residents. But inadequate planning support, Fuchs noted, is “a massive problem, especially in resource-deficient rural areas. Communities that have not been properly supported in their mitigation, climate adaptation, or even emergency response planning efforts can find themselves far less prepared for disaster situations.” Those communities are more likely to flounder in emergencies, raising the risk that disasters become catastrophes.

The struggle to meet local planning needs

Municipalities along Maine’s low-lying southern coast now experience routine flooding around King Tides, said Abbie Sherwin, a senior planner with the Southern Maine Planning and Development Commission “but understanding what to do about it is far more complicated.” Efforts to mitigate particular hazards often merge into the broader work of climate resilience, a far-reaching effort that may include infrastructure upgrades, ordinance changes, public health measures, production of clean energy and local foods, steps to reduce waste and power, and a host of other actions designed to reduce carbon emissions and to better withstand climate shocks. In that broader work, Sherwin added, there’s “a need for sustained support and planning,” among all of the Commission’s 39 member communities, one that far surpasses the organization’s current capacity.

Esperanza Stancioff, climate change lead for University of Maine Cooperative Extension and Maine Sea Grant, co-coordinates similar resilience efforts through the Climate Change Adaptation Providers Network and a group working to help communities around Passamaquoddy Bay and along the western shore of Penobscot Bay. Towns in Washington County recently lost all regional planning support and have been in a crisis mode, she explained, struggling to even recreate what studies and assessments have been done in the past. There’s a wealth of resources to help towns in resilience planning, she noted, but “tools can only be used when there’s capacity.”

Needed: more boots on the ground

To build that local capacity, Maine should launch the proposed Maine Climate Corps (recommended in a report the Maine Commission on Community Service delivered to the Legislature this week), which would place corps members on a range of local projects, including ones focused on “community resilience planning assistance” and “emergency management community assistance.” Greater Portland Council of Governments is already piloting a nine-member “Resilience Corps,” four of whom are working with local communities on climate preparedness.

Volunteer Organizations Active in Disaster (VOAD) is another “model (that) works really well and doesn’t take state resources,” Montano explained. It encourages nonprofits and other community organizations to coordinate and communicate on response and recovery. “It can be hard keeping (groups) active when a disaster is not happening,” she cautioned, but there’s “potential for them to be taking ownership of more mitigation work.” For that model to work in Maine, participation would need to increase markedly. Maine’s VOAD currently has an outdated website and only 125 followers on its Facebook page.

Some help on the way

The Governor’s Office of Policy Innovation and the Future (GOPIF) recently launched the Community Resilience Partnership (CRP), a $4.75 million program that will award grants, targeting many toward 71 activities designed to reduce carbon emissions, advance clean energy and increase resilience — including some disaster mitigation and preparedness measures. The specified activities qualify for no-match grants and, in Fuchs’ words, help “spell out a process” for resource-strapped communities so it’s “not so overwhelming.” Communities can receive ongoing support from service providers and a pilot group of regional coordinators with climate expertise.

The CRP seeks to address the planning disparities revealed in the Maine Climate Council’s vulnerability mapping, according to Anthony Ronzio, GOPIF deputy director. “Additional grant funds are available to service providers to assist smaller communities with populations below 4,000 and communities with the highest social vulnerability.”

The leading recommendation made by the council’s emergency management subgroup is taking shape in a $20 million infrastructure adaptation fund that will be administered by the Maine Department of Transportation to help communities make the local match required by federal grants such as FEMA hazard mitigation grants.

In addition to these new programs, Maine should consider other measures to fund response and recovery efforts, particularly given the slow and cumbersome delivery of federal disaster relief. Maine could choose to self-insure through a catastrophe bond or adopt a parcel transfer tax to fund preparedness — as Marin County, California residents recently did.

Maine is in the enviable position, Montano noted, of having no “major recovery operation going on,” making this an opportune time to undertake disaster mitigation and preparedness, develop additional funding mechanisms, launch a Climate Corps and reinvigorate the state’s VOAD. Investing time and resources now will give Maine residents the best possible chance of dodging disaster.