COLUMBIA — Derrick Ray watches customers buy lottery tickets with mixed emotions.

As manager of Columbia’s 4-Corners Shop ’n Save, a small grocery in Washington County, he knows the lottery is good for business. Last year, the store sold $237,000 worth of draw games and instant tickets, or about $488 for every person in town. The store receives commissions and sometimes, bonuses. And many who buy lottery tickets also pick up a Slim Jim, a pack of cigarettes or even a week’s worth of groceries.

But Ray also sees some downsides.

“We must have 20-25 regulars who buy every day,” he said. “Sometimes I feel bad selling those people tickets. I guess I shouldn’t. It’s their choice, right?”

He also wonders about the money.

“Since 1970, they advertise all these billions of dollars they’ve sent to the General Fund. How weird. Where does it all go?”

Until now, such questions about the costs and benefits of Maine’s state-run lottery have received little public scrutiny. In part, this is because the lottery operates like an independent business within state government, making most decisions internally, with minimal legislative oversight and an eye toward the bottom line, interviews and documents revealed.

“They basically run their own business,” said state Rep. Louis Luchini, D-Ellsworth, chair of the legislative committee that oversees the lottery. “From an oversight perspective, they’re authorized to more or less do what they want.”

At the same time, the lottery generates $50 million annually for the state’s General Fund — dollars that would otherwise need to come from higher taxes — welcome income that shields the lottery from the kind of scrutiny directed at most state agencies, which are drains on the budget, a Maine Center for Public Interest Reporting investigation has found.

The state has never studied the lottery’s impacts on the poor and keeps no data on addiction rates, making it difficult to assess the true costs and benefits of the state-run lottery.

Officials dispute this critique. They cite their significant contribution to the state’s General Fund and their lean operating budget as proof the lottery carries its own weight. The $50 million the lottery contributes annually to the General Fund represents about 1.5 percent of the total state budget.

“The question I would pose, and I’d say this to a legislator: If you want to get out of the business of the lottery, or spirits business, you’ve got to be able to replace the lost revenue,” said Tim Poulin, the lottery’s deputy director. “Where are you going to find that money?”

WINNERS AND LOSERS

The winners far outnumber losers, lottery officials said. “When you play the lottery, everyone wins. Retailers win. And so does Maine’s General Fund,” said Poulin.

Since 1974, the lottery has paid out $2.8 billion in prizes to its players. Store owners who sold winning tickets have received $327 million in commission and bonuses. And the general fund, the state’s primary operating budget, has taken in more than $1.1 billion, according to the lottery’s December 2014 financial statement.

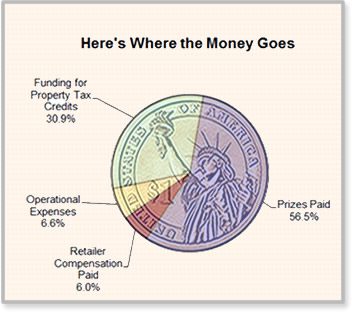

The lottery itself, meanwhile, operates with 23 full-time employees, plus a director and deputy, officials said. It gives 60 percent of its revenue back to its players in prizes ranging from a few dollars to more than $100 million.

“Some of my own friends, say, ‘You’re worse than a casino,’” said Poulin, the lottery’s deputy director. “But actually, we’re better. The percentage we give back to players is more than a casino might provide,” he said.

The game’s losers, however, receive much less attention.

An exclusive Maine Center for Public Interest Reporting analysis of lottery sales revenue, examined in conjunction with Cornell University, shows that Mainers living in towns with low incomes and high unemployment spend far more on lottery games than those living in the most well-off communities.

For every one percent increase in joblessness in a given zip code, lottery sales jump 10 percent, the original research shows. And people in Maine’s poorest regions spend as much as 200 times more person than those in wealthier areas.

Until now, neither the lottery nor the Department of Health and Human Services had ever analyzed or reviewed this data. None of the lottery’s $230 million in annual sales revenue is dedicated to studying, or defraying, the lottery’s social impacts on Maine’s poor and working class.

The state does not know how many people are addicted.

Former Republican lawmaker Peter Mills, who paid close attention the state’s involvement in gambling over 15 years in the Maine legislature, said the money generated by the lottery has made it nearly immune to scrutiny.

“The state is drunk on the revenue,” said Mills. “The political backdrop is, no one cares about these people. They have no constituency. The fact that this money should be spent on groceries for their children doesn’t seem to matter.”

POLITICIAN’S DREAM

Many states, recognizing these well-researched pitfalls of a public-run lottery, earmark sales revenue for education and other aid programs, with an eye towards making a “vice” pay for a public good, according to a 2007 study of state lotteries.

Pennsylvania has dedicated a portion of lottery revenues to a prescription drug program. Wisconsin has earmarked lottery funds for property tax relief. Kansas allocated $15 million of its $208 million in lottery sales to problem gambling assistance.

But in Maine, revenue from lottery sales is mingled with taxes on income, cigarettes, sales and corporations, then deposited into the state’s general operating fund, where it becomes impossible to track how it is used, said Maureen Dawson, a state legislative budget analyst.

“It’s kind of like having multiple sources of income all going to the same checking account, then trying to figure out which source paid for the toaster you bought,” she said.

Aside from a small portion — less than 1% — dedicated to conservation, Maine legislators have consistently voted down proposals to dedicate revenues to specific causes, beef up oversight of the lottery or earmark revenue for problem gambling, a review of historical bills pertaining to the lottery shows.

In 1995, a bill entitled “An Act to Dedicate the State Lottery Funds for School Funding,” was voted down. A 1999 bill called “An Act to Reduce Hunger in Maine” also failed. Legislation to create games to fund school scholarships, pay for quality early childcare and education, and benefit breast cancer education all failed as well.

“It’s a politician’s dream,” says Cornell researcher David Just, an economist who has studied the costs and benefits of lotteries nationwide. “No one complains about raising taxes, and there’s no accountability for what it’s used for.”

BIG MONEY, LITTLE OVERSIGHT

Maine’s lottery generates government funding that might otherwise require raising taxes, anathema to elected officials everywhere. Yet when presented with the findings from this work, lawmakers from both parties said they wondered whether the ends justified the means.

“What we’re doing is a squeezing a sponge here,” said state Sen. David Burns, R-Whiting. Washington County, which Burns represents, has the state’s highest rates of unemployment and poverty — and its biggest-spending lottery players, the data shows. Residents spend as much as $1,300 per person per year in some towns.

“The amount of money we get back from the lottery is not proportional to the poverty we have in Washington County. We’re taking money from people who can least afford it,” Burns said.

“I’m very concerned about the ethics of this,” he said.

State Rep. Beth Turner, R-Burlington, also from Washington County, worries that lottery revenue comes too easily, leading to wasteful spending.

“I look at government like a household. The more you make, the more you spend. With a $50 million hole, we might prioritize things a little differently,” she said.

State Rep. Louis Luchini, a Democrat and co-chair of the legislative committee that oversees the lottery, said a more careful look may be warranted.

“It makes sense that if the state is going to legalize gambling in a lottery, there should be something done to calculate the social costs. Because it certainly doesn’t come without a social cost,” he said.

The big money and high stakes have raised eyebrows before.

In 2007, lawmakers asked the legislature’s investigative arm, the Office of Program Evaluation and Government Accountability (OPEGA), to answer questions about lottery operations.

“What was the original legislative intent for use of lottery funds, and has that changed over the lottery’s history? What does the Maine lottery consider when making decisions about games to be offered and how they will be marketed? Who has responsibility for making and overseeing those decisions?” lawmakers asked.

A backlog of work has delayed the study, Luchini said. But he said lottery officials are just doing their job.

“If there is a policy question here, that falls to the legislature,” he said.