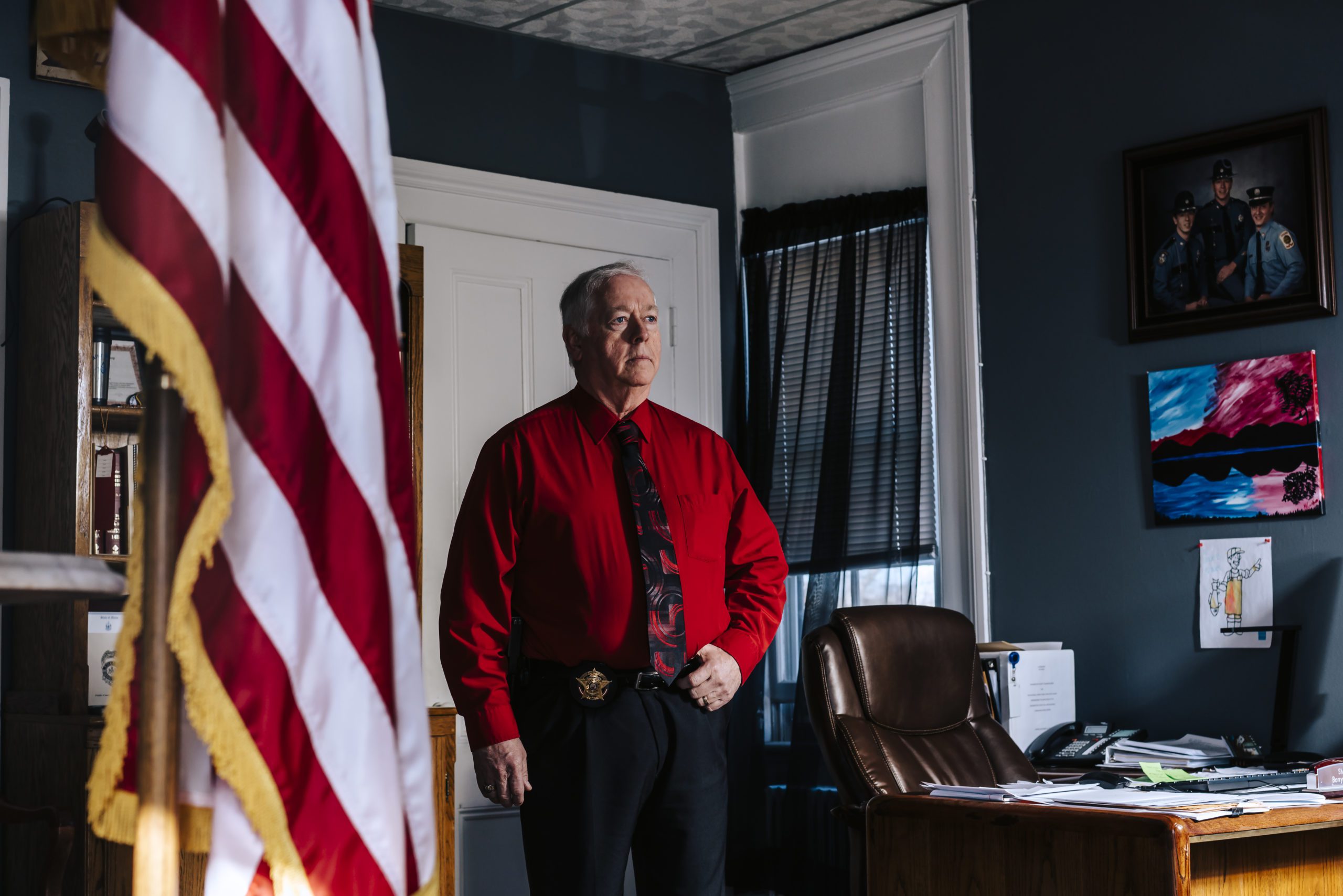

When he was elected sheriff in 2014, Barry Curtis told Washington County voters he would address the county’s drug problem head on.

After 25 years as a state trooper — the last 15 in Washington and Hancock counties — he felt well prepared for the job. When he returned to law enforcement after a four-year break, he noticed things had changed. There was something different about how cases progressed through the criminal justice system.

They weren’t moving along as quickly as they used to. When his officers were working on cases and needed advice, it was hard to find anyone in the district attorney’s office to answer questions. Crimes, particularly those related to drugs, were more frequent and more serious than when he was a trooper.

“When I was on the Maine State Police, Friday and Saturday night you were extremely busy,” he said. “Now I’m sitting in this chair here — it’s busy every day. There’s no break. It used to be winters it would slow down, but it’s just nonstop. You’ve got all your drug problems down here. Every crime we have will basically roll right back to a drug problem.”

For those reasons — and myriad others outlined by various Washington County officials in recent weeks — many believe it’s time for the county to get its own district attorney and stop sharing one with neighboring Hancock County. They point out the significant differences between the counties — Hancock has nearly 23,000 more people and its residents’ median income is $51,438 compared to $38,239 in Washington County. Culturally, Washington County has a far larger Native American population — governed in part by its own law enforcement and legal system — than any other county in Maine.

RELATED Due Process: Inside Maine’s County Court System

In the 45 years there has been an elected district attorney for Prosecutorial District 7, the Hancock/Washington district, never has one come from Washington County. That lack of representation is of particular concern to Jeffrey Davidson, a defense attorney who has practiced in Washington County for 16 years and whose office is right across from the courthouse in Machias, the county seat.

“It’s nice to have the person you vote for to be accountable to you directly,” he said.

Davidson, Curtis, the Passamaquoddy Police chief and all members of the Washington County Commission support a bill pending in the state Legislature, LD 1967, that calls for a citizen vote in November to see if residents in Washington and Hancock counties want to separate the district so that Washington County can have a DA of its own. The Judiciary Committee voted 8-0 on Feb. 26 in favor of the bill, which now heads to the House of Representatives for consideration. A decision is expected by the end of the legislative session in mid-April.

If the bill passes and voters approve the idea in November, it would be the first change to the state’s eight prosecutorial districts in more than 40 years.

Other elected officials — namely Maine House and Senate members — have their districts re-examined every 10 years to ensure they are properly proportioned and reflective of population shifts. But the configuration of prosecutorial districts has not been amended since a 1973 state law changed the district attorney system from each of Maine’s 16 counties having its own DA to just eight statewide, according to the legislative record provided by the Maine State Law and Legislative Reference Library.

Despite broad support for the move, Washington/Hancock District Attorney Matthew Foster warned that splitting the district will not address one major problem: He can’t find attorneys who want to work in Washington County. His office is understaffed.

“It’s like proposing to build a school and not having any teachers to teach at it,” he said.

For more than seven months, the Maine Monitor has examined the state’s county court system to look for instances of inconsistency and fairness in how cases are handled across the state. Who serves as the local district attorney — and how they set policy, pursue cases and implement reforms — can have a big impact on crime and punishment in one part of the state versus another.

For Curtis, the sheriff, finding a way to get a close partner in the district attorney’s office to fight drug crimes in Washington County is a priority.

“There’s a reason we have this drug problem down here,” Curtis said. “We’re not heavily manned by law enforcement and (dealers) saw us as an easy target. We want them out.”

‘This is a big place’

On a mid-February afternoon, Curtis and his chief deputy, Michael Crabtree, brewed a fresh pot of coffee in Curtis’ office while listing the reasons they feel a DA dedicated only to Washington County is essential to fighting the type of crime they now see.

“We haven’t got anybody to speak to about some of these cases,” the sheriff said as he sat behind his desk covered in paperwork in Machias. “We’d like to be able to have somebody in the office so when we have a problem with a case we could step over and discuss it. The cases in Washington County have become a lot different than what we used to do.”

For example, Crabtree said although comprehensive statistics are difficult to point to, internal data from the sheriff’s department showed a dramatic increase in armed robberies in 2018, when they jumped from one to six or seven.

Washington County Commission Chairman Christopher Gardner, a former deputy sheriff and Eastport police officer, said when he began his career in law enforcement in the late 1990s, prescription drugs started to become a serious problem. Over time he saw crime go from people sharing prescriptions to what he called “the business phase,” when people from out of town started bringing drugs into the county to sell.

“It’s not just local people dealing with a local addiction problem,” he said. “The world has found us. It’s a business opportunity now. That’s why we’re seeing some of the importation.”

Curtis and Gardner said a lot of time goes into building a case, particularly when reviewing evidence such as dashboard cameras and other recordings. Police need a consistent partner in the district attorney’s office to make sure they have the evidence they need when a case goes to court, Curtis said.

“Because of the seriousness of everything we’ve got going, we really need to have the attention of the DA and the people in that office,” he said. “If we’re missing something in a case, we’d like to be able to fix it so that when we go to court, we wouldn’t have any problems.”

Davidson, the Machias-based defense attorney, said there are other important considerations. He said the state requires each prosecutorial district to have one assistant district attorney designated to handle drug cases, and that person for District 7 is based in Hancock County. That means the Washington County drug cases are handed off to other assistant district attorneys who are not always familiar with the cases, he said.

“We’re literally over in court sometimes with DAs who are not as familiar with the files that they need to be,” he said. “They have not sat down and listened to all the recordings. They haven’t read all the police reports. And it’s apparent.”

Crabtree said recent turnover in the district attorney’s office has exacerbated the problems. Longtime DA Michael Povich, who served from 1975-2010, assigned an experienced prosecutor to handle Washington County cases, although Povich himself rarely came to the county, said Crabtree and Davidson.

When Povich retired, he was replaced by Carletta Bassano, who served one term, from 2011-14. Foster has been the DA since 2015. Part of the difficulty is that although there are three assistant district attorney positions assigned to Washington County, Foster has only been able to find one full-time and one part-time attorney to handle cases there, he said.

Foster told lawmakers on the Judiciary Committee in late January that he did not want to take a position supporting or opposing the bill that would split his district. He explained the problems he’s had filling positions, saying he’s been advertising for six months and has received no applications. He also noted that it’s difficult for him to manage offices in Calais and Machias in addition to his Hancock County office in Ellsworth.

“Personally, not having to drive over two hours to Calais would be wonderful,” he said. “It takes away time for me to do my job. It’s very difficult to manage people two hours away.”

In addition to the Calais courthouse, Foster travels from his home base in Ellsworth to the courthouse in Machias, which takes an hour and 20 minutes. If he needed to travel to Eastport, it’s a 2 hour and 15 minute drive from Ellsworth.

“Geographically this is a big place,” Chief Deputy Crabtree said. “Maybe the time has come that we should think about this and see if it may not work better the other way.”

Aroostook County — larger geographically but also sparsely populated, like Washington County — has its own DA. When it comes to annual caseloads, the totals for District 7 and District 8 (Aroostook) are nearly identical, with District 8 handling 6,519 cases and District 7, Hancock and Washington, handling 6,591, according to the 2018 Maine Judicial Branch Annual Report.

Broken down by county, there were 3,988 cases in Hancock County and 2,603 in Washington County in 2018, the report states.

With the current configuration of eight prosecutorial districts statewide, those two regions handle far fewer cases than the rest of the state. District 2, Cumberland County, handled 18,661 in 2018, followed by District 3, Franklin, Oxford and Androscoggin, with 17,365.

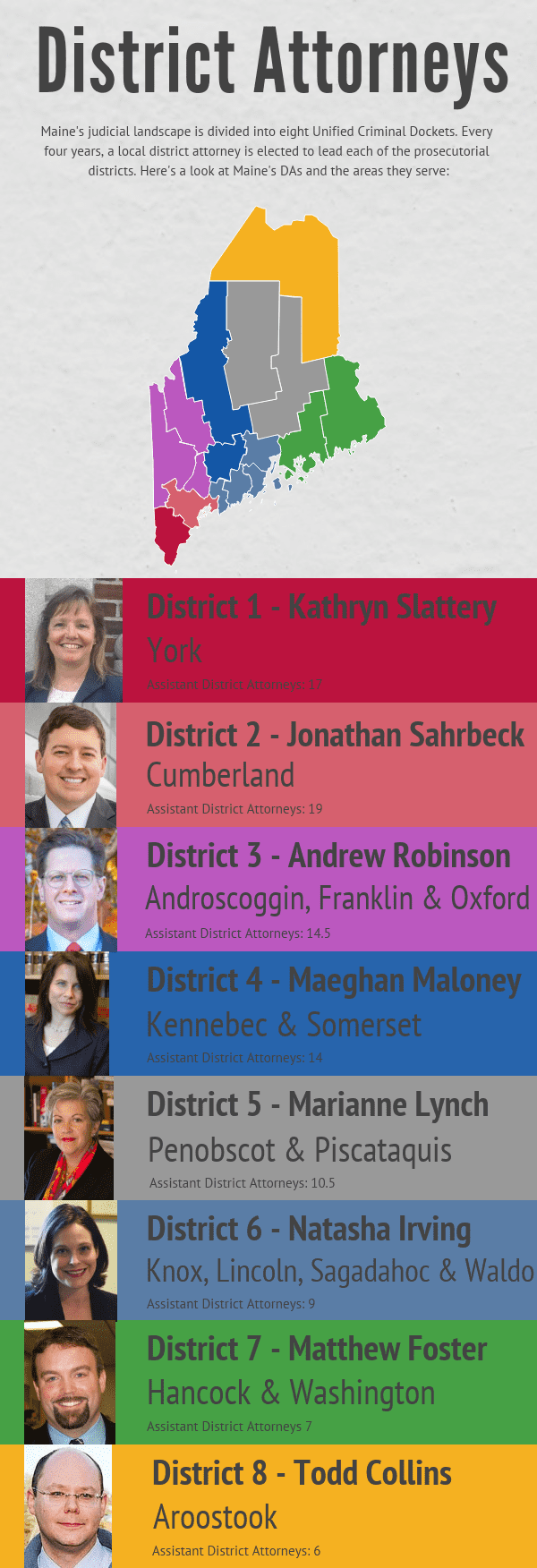

When it comes to DAs covering multiple counties, five of the eight current DAs cover more than one county, with Natasha Irving in District 6, covering four counties — Waldo, Knox, Lincoln and Sagadahoc.

How we got here

In March 1973, the Legislature considered a bill to “provide for a modern democratic system for the effective prosecution of criminal cases,” according to the legislative record. The bill summary notes that district attorneys would continue to be elected but that creating districts instead of having a county-by-county system would even out caseloads and increase pay across the state.

There’s no mention of what the DAs were being paid at the time, but the bill ensured that all eight of them in the newly created districts would make $23,500 a year. (Current DA salaries range from $84,926 to $122,387, according to the state Department of Administrative and Financial Services.)

“This important sector of the Maine criminal justice system will become more effective and remain a democratic institution,” the bill summary states. “Prompt and effective prosecutions will be promoted by adequate staffs for consultation and for case preparation.”

The Maine Prosecutors’ Association — which at the time included 11 Republicans and five Democrats — supported the change, particularly because it continued the practice of electing local DAs. Other bills had proposed to have the attorney general or governor appoint district attorneys.

“Local prosecutors exercise a large degree of power and discretion in setting priorities, establishing policies and procedures, in initiating investigations, in deciding to bring charges and in recommending disposition of cases,” the association wrote in a memo to lawmakers. “Law enforcement problems differ throughout the state and only prosecutors operating independently in the area can adjust to meet required needs.”

The law, passed in 1973, called for the first election of the new district attorneys to be held in November 1974. The new group of DAs were sworn in for their four-year terms on Jan. 1, 1975.

Time for change?

One idea floated at the public hearing on LD 1967 this year was to re-examine all prosecutorial districts in Maine to ensure that they are adequately addressing needs specific to their regions.

Sen. Michael Carpenter (D-Houlton) asked Kennebec/Somerset District Attorney Maeghan Maloney if she thought it was time to evaluate all the districts. Maloney, who testified neither for nor against the bill as a representative of the Maine Prosecutors’ Association, said she didn’t oppose the idea but that the concerns expressed by Washington County officials seemed unique to their part of the state.

For example, she said she doesn’t have a hard time filling vacant positions and was told by law enforcement in Somerset County that even though her office is in Augusta, they feel she’s doing a good job.

“The Washington County concerns are very different, depending on where you live in the state,” Maloney said.

One difference is that Washington County is home to two Passamaquoddy reservations, which means they have their own police departments and judicial system, in addition to tribal game wardens. Population-wise, more than 5 percent of Washington County is Native American, the highest in the state. Aroostook County is second at 1.9 percent, according to census data.

Passamaquoddy Police Chief Matthew Dana II, who took over as chief in October, said it’s hard for people who don’t regularly prosecute cases in Washington County to understand how tribal law and state courts share jurisdiction in some cases.

“The intricacies and the complexity of Indian law versus state law and jurisdiction, where the lines lie, it’s hard to know if you don’t live it every day,” he said during an interview at the police station in Indian Township.

Last fall, Dana said he called an assistant district attorney for advice on a case and she expressed frustration at trying to sort out the details.

“Her response was, ‘Well, that’s why I hate tribal law,’” he said. “She just doesn’t deal with it every day.”

For example, misdemeanor cases can be heard in tribal court, but charges against non-tribal members go to state court. Felonies go to state court, too.

There are five reservations in Maine, including the two in Washington County. Dana said there are three tribal police agencies in the state, two in Washington County – Indian Township and Pleasant Point. In addition, there are tribal game wardens who also may need to work with a local prosecutor on cases involving hunting and fishing violations.

Back in Machias, Davidson, the local defense attorney, said from the time he started practicing in Washington County in 2004, he felt the county needed its own district attorney.

“With the onslaught of the heroin epidemic up here, it also brought in the dealers,” he said. “Before it was local people getting a prescription from their doctor and selling it to their friends, but everybody knew what they were getting. Now you have dealers from out of state who don’t value life quite as much as we do.”

Davidson said 10 to 15 years ago, “it was unheard of” for out-of-state drug dealers to come into Washington County. But what started as an epidemic of oxycontin addiction has evolved to what he described as a “heroin epidemic.”

Gardner, the county commissioner, said the changing criminal landscape has shined a light on the need for more of everything – treatment options, law enforcement and a local district attorney focused on just Washington County.

“There’s not enough police officers, there’s not enough judges, there’s not enough court days, there’s not enough district attorneys, there’s not enough of all of that,” he said while sitting in his office with a view of Eastport Harbor.

Gardner said there’s also a need to provide education and treatment options for people struggling to get away from drugs and drug crime.

As a county commissioner, Gardner said he’s working to bring attention to the need for a local district attorney, partly because it’s something he can control. While the state pays district attorneys and assistant district attorneys, the counties pick up the costs to run and staff the offices.

The Washington County portion of the District 7 budget is $304,500 and Hancock County’s is $399,189, according to Gardner. He and others are proposing that Washington County continue to have three attorney positions, but increase one of the three current assistant district attorney salaries to a full district attorney position.

That would create a cost to the state, depending on how much money is currently allocated for the assistant DA positions. The pay range for ADAs is quite large – from $54,953 to $110,905, depending on when someone entered the bar and their years of experience, according to Kyle Hadyniak, director of communications for the Department of Administrative and Financial Services.

Pay for district attorneys ranges from $84,926 to $122,387.

And while it may help his law practice, which focuses on criminal defense, Davidson said he moved back to Washington County from Louisiana to raise his family. He doesn’t want more crime coming here.

“I have to live in this area,” he said. “You go for a walk on the trails and you see needles on the side of the trails. That doesn’t benefit me.”

There are other advantages to having local prosecutors. Davidson said for those who work in the community, it’s easy to distinguish between a defendant who may benefit from a treatment program and one who should be jailed. But for a prosecutor unfamiliar with the community, it’s much more difficult.

“It’s very easy for us who have been down here working it, and for the police, to understand who is an addict who is selling a pill to a friend to feed his addiction and who is a drug dealer out for himself and making money,” Davidson said. “One of them needs to be diverted. The other needs to be incarcerated. It’s obvious.”

What happens next

The bill to separate District 7, sponsored by Rep. William Tuell (R-East Machias) now heads to the House for consideration. In expressing his support for the legislation, Tuell said he felt it was important for voters to decide whether they want to create a separate district. Approval by the Legislature now would allow a public vote in November. If creating a new district is supported, it would give Washington and Hancock counties time to plan for a transition prior to the 2022 election – the next election in the four-year district attorney cycle.

“(The bill) gives them a chance to vote on whether to continue a partnership established in the early ’70s or find new solutions that are more respectful of the demographic changes and geographic realities that have brought this bill before us today,” Tuell said.

During the work session on the bill, Commissioner Gardner assured lawmakers that Washington County is prepared to pick up the cost of adding a referendum question to the November ballot. Hancock County Administrator Scott Adkins, contacted via email after the work session, said he did not have any comment on the bill.

Curtis said the arrest of 26 suspected drug dealers last year, with the help of the FBI, Maine Drug Enforcement Agency and border patrol, was a big victory for law enforcement. And just last week, the MDEA arrested another four people in Washington County, charging them with unlawful trafficking in heroin. As the Legislature mulls LD 1967, Curtis said he will be watching closely.

“As the sheriff here I’m really anxious to see if this is going to pass,” he said. “I really think this is going to benefit us and the people of Washington County like you would not believe.”