For the first time since a voter initiative passed in 2004, the Maine state government will meet its obligated 55% share of the cost of public K-12 education.

An increase in state revenue coupled with federal funds that went to eligible projects freed up the money needed to fund education at a rate set by voters 17 years ago.

The total K-12 state funding of more than $1.3 billion for fiscal year 2022 was celebrated by Democrats and the Mills administration as an unprecedented victory — and it was, in the sense that the requirement had never been achieved.

But can the 55% state funding commitment continue?

Rep. Michael Brennan (D-Portland), who chairs the House Education Committee, said he was proud to finally see “a true 55%” passed, adding that the figure has proved “elusive” in recent years.

As for the future, Brennan said that because education, especially with community colleges and universities included, makes up such a large percentage of the budget, it’s often the first to see cuts when the state isn’t doing as well financially.

But even if that were to happen in two years, he said it will be hard for the legislature to backtrack now that it has met the obligation.

“I do believe we’ll be able to sustain this in the next biennium budget. And I believe that because once getting to 55%, it’s going to be very difficult for the legislature to go back from that,” Brennan said. “It’s going to be in the best interest of public education in the state of Maine, and I think politically it’s going to be very difficult.”

School administrators said the funds help the community by providing local property tax relief for residents.

“That’s what it means for us in this district,” said James Boothby, Regional School Unit 25 superintendent and president of the Maine School Superintendent Association. RSU 25 includes Bucksport and surrounding towns.

“You know, education is by far, by far the largest commitment most communities make, and their taxation is committed toward education. So anytime that we can provide an opportunity to lower that obligation, it’s a good thing.”

Continuing to meet the 55% obligation is popular, good politically and helps the community, Boothby said.

“But you don’t know, and that changes with every biennial budget,” he said. “It is a year-to-year situation. You can do your best for pre-planning and finding ways in which you can get creative to afford things. In the end, each year, the amount of revenue the state will take in determines the amount of money that they’ll put into education.”

If the 55% funding level went away, the cost would go back to local taxpayers, said Yarmouth Superintendent of Schools Andrew Dolloff.

“Taxpayers would be asked to fund higher levels of local education costs, and students would suffer from a likely reduction in programs and services due to reduced state aid,” Dolloff said in an email.

Higher property taxes can lead to bitter fights over school budgets, Dolloff said.

“Normal inflation combined with lower state aid would drive that increase to a higher number than many would be comfortable with, leading to divisive campaigns that pit neighbors against one another as they consider whether or not to support the school budget in their community,” he said.

Because Yarmouth is a lower receiver of state education, the funding doesn’t have as much of an impact. But, Dolloff said, “The shift toward greater state contributions to education will impact everyone.”

A lot can change over two years, when the Maine Legislature must pass its next biennial budget. It’s unclear what the economy will look like or what effect the COVID-19 pandemic will still be having.

If the money dries up

Some say it will be hard to continue implementing the funding without the excess revenue that was available in preparing this budget.

Jim Rier, who spent more than a decade in various education positions in Maine, including chairman of the Maine Board of Education, said meeting the 55% funding goal was an important step that took longer to reach than he imagined.

“We all realized it would take time, but I don’t think we realized it would take this much time,” he said.

Rier also noted there has been debate between Democrats and Republicans concerning the way retirement is calculated into the 55% share. Under former Gov. Paul LePage, all education retirement plans, which would be paid by the state regardless, were included in the 55%. Under that calculation, the funding requirement was already met.

Education advocates, however, feel that pension costs should not be included, especially because it was not in the original law. That’s why, to them, this new biennial budget is the first time 55% was actually met.

“The Education Committee and some in the education community wouldn’t have paid any attention to the total contribution by the state as to include retirement. They just never accepted that,” Rier said.

The recently enacted federal American Rescue Program authorized hundreds of millions of dollars to be sent to Maine state government, counties and municipalities in the name of economic recovery, while the nation is in the midst of COVD-19.

While that federally allocated money will not be spent on ongoing education costs per se, “it helped move enough things around” to free up the dollars for Maine K-12 education.

What happens when the federal stimulus money runs out?

“It’s going to make meeting that number much more difficult in the future when the next biennial has to be done,” Rier said. “Whether they can continue to meet the 55%, the way it’s defined now, is a question.”

Kelli Deveaux, the Maine Department of Education communication director, didn’t want to speculate about something two years away.

“While it would not be prudent for us to attempt to predict the future, as we have no way of knowing what the legislature will do with appropriating funds or making changes to the model that may impact the total cost of education, it is the intent of the Mills administration to continue to prioritize a 55% state share of the total cost of education,” Deveaux said in an email.

An ‘honest calculation’

Kate Dufour, director of state and federal relations for the Maine Municipal Association, said term limits for legislators also impact the ability to know what policies or funding can last in the long run. Plus, changing governors, their administrations and legislatures is part of the reason it took so long to reach the goal in the first place, she said.

After years of redefining and delaying implementation of the 55% obligation, Dufour said this biennial “is based on what I call an honest calculation of what it takes to educate students in the state of Maine.”

Moving forward, things could change, but that doesn’t mean there shouldn’t be praise for this budget, she said. In particular, she said the entire state budget helped relieve local property taxes.

“That budget is full of property tax relief, not just for K-12 education, but also for revenue sharing, the enhanced reimbursements to communities for homesteads,” she said. “So they’re committed to property tax relief, and helping municipalities fund the cost of local government services.”

Regardless of what the funding is, there is always concern for longevity, and K-12 funding is no different.

“We’re always worried about that,” she said of losing the funding. “We could be having a really fantastic economy, and the state is pulling in sales and income tax like nobody’s business. There’s still no guarantee the next legislature (will fund it), so that’s always there.”

Rep. Paul Stearns (R-Guilford), the ranking member for the House education committee, said with the increase in state revenue and the influx of federal dollars, Gov. Janet Mills saw it as a good time to go for 55%.

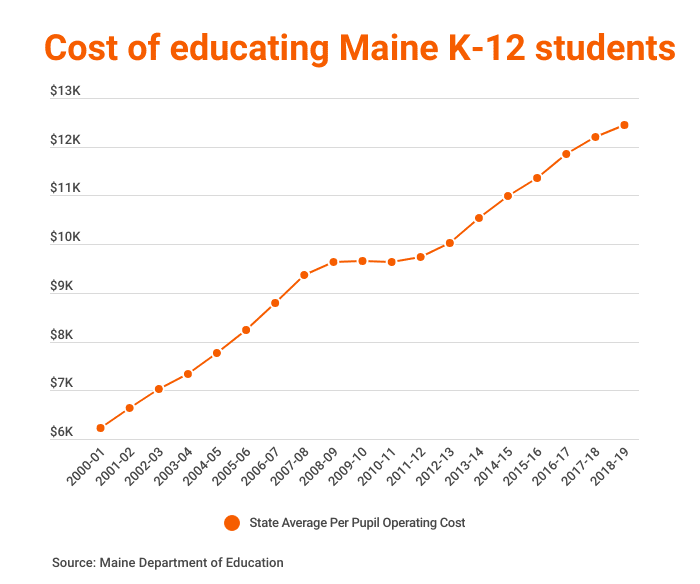

Stearns does have questions about education spending. For example, he wondered why education spending continues to rise even though the number of students is falling in Maine.

“In my opinion, perhaps it would have been more prudent to take a smaller step. But we’ll see. What I would like to see them do is really examine the cost centers and find out what is driving the increase in K-12,” Stearns said.

Unlike some of his GOP colleagues, Stearns said total retirement should not be included in reaching 55% because it wasn’t part of the original language. He compared it to changing the scale from pounds to kilograms.

Whether the money will be there to keep up the funding in the next budget, Stearns said time will tell.

“I don’t have a crystal ball,” he said.