Summer in Maine is construction season. For months, we’ve been surrounded by people digging up roads, putting in new pipes, laying pavement, building houses. There are solar panels going up, wind turbine blades being ferried from place to place.

The Biden Administration hopes we’re in not just a season, but an infrastructure decade. In the past few years, Congress has allocated more than $1.75 trillion for transportation, energy, water resources and broadband, money that is intended to be spent over the next five to ten years.

Getting that money out the door and spending it on the things it was intended for is, of course, the hard part. Decisions over what projects get built, how they’re designed, who’s going to build them, where they’re going to go — those choices will happen at the state and local level.

That allows people to have a say in what’s appropriate for their communities. But it also means many of these projects may never materialize, hung up in reviews and permitting processes.

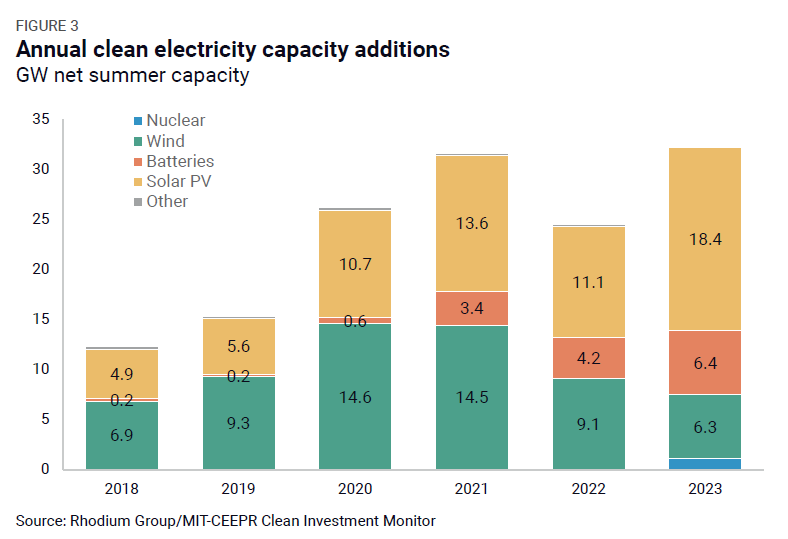

The U.S. added a record amount of energy from solar, wind and batteries to the grid last year – around 40 gigawatts. Another 63 gigawatts are planned for this year.

But an analysis by three groups tracking the implementation of the Inflation Reduction Act and the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act suggests that won’t be enough to meet our emissions reduction targets, which will require adding roughly 70 to 126 gigawatts of renewable electricity capacity each year between 2025 and 2030.

If we don’t make it easier to build large infrastructure projects, particularly the transmission lines that are currently one of the primary hurdles to adding renewables to the grid, the analysts wrote, we likely won’t meet those goals.

“The biggest barriers to deployment between now and 2030 are non-cost in nature—like siting and permitting delays, backlogged grid interconnect queues, and supply chain challenges.”

Enter the Energy Permitting Reform Act of 2024.

It sounds boring, but the implications could be huge. Broadly speaking, the bill is a very messy compromise that would make it easier to build transmission lines, boosting the connection of solar and wind to the grid, while also giving a leg up to the fossil fuel industry, opening public lands and waters to oil and gas leasing, and simplifying the process of exporting natural gas. Here’s a breakdown of the provisions.

Environmental groups do not agree on whether the compromise is worth it. The Natural Resources Defense Council and League of Conservation Voters oppose the legislation, as do activist Bill McKibben and many other prominent environmental advocates.

Sen. Bernie Sanders (D-VT) voted against it in committee, saying, “Just one provision in this bill … will greenlight five massive [liquid natural gas] projects that will lock in annual carbon emissions equal to 165 coal plants.”

But the renewable energy industry and others say it’s crucial to reducing emissions and speeding up the permitting process. The bill passed out of committee with a rare bipartisan majority — 15 to 4, with Sen. Angus King (I-ME) in favor — and is now in the hands of the Senate.

“We have to have the transmission changes in order to get to the clean energy future. It’s a bottleneck,” said King. “In my view, if we vote for this bill, it will get us enormous benefits in terms of emissions, and it will speed the transition. If we vote against, we will have a slower transition and fewer emissions reductions.”

(King and several other senators teamed up on two amendments that would have banned oil and gas leasing in the outer continental shelf off New England and the West Coast. Both failed 9-10.)

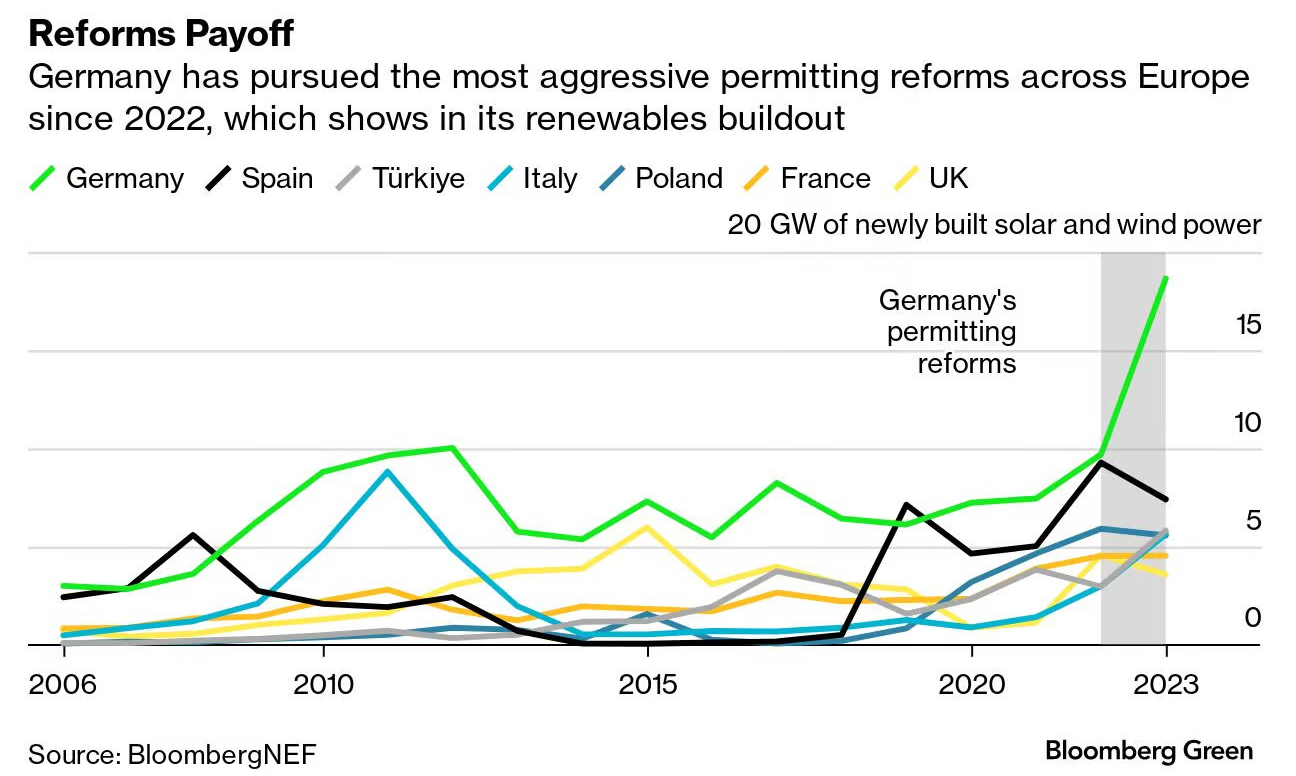

As for what speeding the transition could look like: Germany has seen a record buildout of renewables in recent years, in part because it drastically cut down the time it takes to permit new projects.

Sam Matey, a Mainer who writes the excellent Substack The Weekly Anthropocene and is in favor of the legislation, broke down some of the climate math in a post in early August that you can read here.

The disagreements over EPRA and some of the other projects we’ve seen in Maine in recent years — the CMP corridor, the proposed wind port on Sears Island, the Aroostook power corridor — are laying bare the tensions that are arising in the environmental movement, which I’ve been thinking about for a while now.

For much of its history, environmental advocacy in the United States has largely focused on how to stop things: oil drilling, mountaintop removal, highways, pipelines.

We are now in a time where we need to construct a lot of things, and we need to do it quickly. That’s a big shift in priorities, and it’s causing fracturing among environmental advocacy organizations that have historically been aligned.

It’s also causing a lot of us to have to think hard about what it means to be an environmentalist and a YIMBY (Yes-In-My-Backyard) in a rapidly changing climate.

“If we are going to house the people we care about and if we are going to address the climate crisis, we’re going to see it,” Sen. Brian Schatz (D-HI), said on the New York Times podcast “The Ezra Klein Show” earlier this month. “It can’t all be someplace else.”