Before settlers rushed westward to mine for gold in the mid 1800s, metal was being mined in Maine. As the craze died down out west, word spread of Maine’s potential. A silver rush ensued and scattered operations lasted through the 1900s — until the impacts of two small-scale, coastal metal mines forced legislators to rethink how mines in Maine should operate.

The neighboring mines, which shuttered in the 1970s, caused significant water pollution that is still being cleaned up — on the taxpayers’ dime. After a decades-long standoff on how to regulate the industry, an out-of-state company is seeking to open two mines in rural parts of the state.

Wolfden Resources Corporation is the first company to test Maine’s strict and long-awaited mining regulations. The Canadian exploration mining company is attempting to rezone a portion of land at its Pickett Mountain property to mine for zinc, lead, copper, gold and silver in Penobscot County. It also recently announced plans to drill at a site near Calais called Big Silver.

The two sites are among less than a dozen significant metal deposits across the state, according to the Maine Geological Survey.

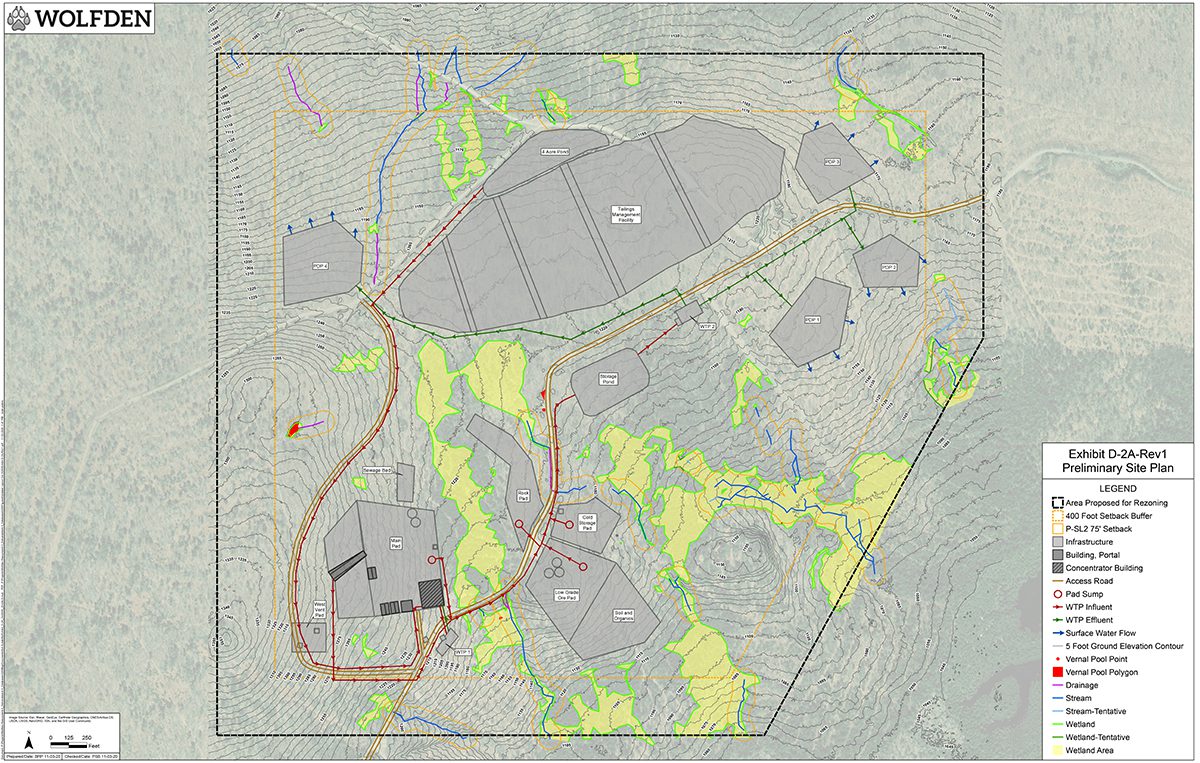

It’s been just over a year since Wolfden submitted a petition to Maine’s Land Use Planning Commission (LUPC) to rezone 528 of its 7,000 acres of land in an unorganized territory near Patten — less than 25 miles from the Katahdin Woods and Water National Monument, and Baxter State Park.

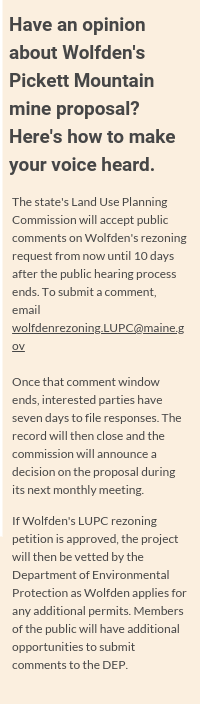

On Thursday, the LUPC gave Wolfden a 60-day deadline to address a variety of concerns with its plans, ranging from the scope of the project to the environmental risks and financial viability.

The commission also pointed out several “significant inconsistencies” between Wolfden’s water management plan and its preliminary economic assessment.

Though the public can submit comments on the project now, Wolfden will have to demonstrate that its wastewater plan is possible and respond to the other requests before a formal hearing takes place.

The public hearing process for the Pickett Mountain rezoning is expected to begin “mid-summer,” according to Stacie Beyer, planning manager at the LUPC.

If the LUPC grants the rezoning request, Wolfden must still secure a permit from the state Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) before it starts mining the area.

Wolfden’s Pickett Mountain project hinges on doing something no other mine has been required to do before: inject treated water back into the ground while keeping surrounding water quality levels equal to or better than they were.

“We were really surprised when (Wolfden) came forward and said they could meet the toughest mining laws in the country,” said Nick Bennett, staff scientist at the Natural Resources Council of Maine (NRCM), who helped write the regulations.

Wolfden claims its Pickett Mountain project will add $230 million in community investments, and create 250 to 300 jobs in Penobscot and Aroostook counties over the 10 to 15 years the mine would be active.

Though the company owns several properties in Canada, Pickett Mountain would be the first Wolfden actually operates as the company attempts to leap from a junior exploration mining company to a developer.

As a junior company, Wolfden finds resources it anticipates will increase in value to spark investor interest, which would fund mining infrastructure and operations. Based on test drills near Pickett Mountain, Wolfden has pegged the site’s value at $1.2 billion. But since the company has no revenue stream until the mining starts, advocacy groups including the NRCM have questioned its financial ability to pull off an unprecedented plan.

The mining group is backed by Altius Minerals Corporation and Kinross Gold Corporation, each with a roughly 10 percent stake in the company.

At least one of the two major investors has been accused of wrongdoing in recent years. In 2018, Kinross Gold faced federal charges after two African subsidiaries it owned contracted with politically favored companies and individuals, and ignored proper payment policies with consultants. Kinross settled the case with a $950,000 payment.

Wolfden’s vice president, Jeremy Ouellette, is confident in the company’s ability to abide by Maine’s tight regulations.

“If we’re given the opportunity to operate, we will make a fantastic example of mining in Maine,” said Ouellette. “Mainers will become miners.”

The rise and fall of mining in Maine

Though Wolfden hopes to usher in a new era of mining in Maine, the favorable price of metal and discovery of a handful of massive sulfide deposits sparked a wave of interest in the early 1970s.

“There’s always been some type of exploration going on since these deposits were found in the ’70s,” said Mark Stebbins, who has worked for the DEP for 31 years and served as its mining coordinator from 1990-2018.

As interest continued to increase into the 1990s, the DEP and Land Use Regulation Commission (now LUPC) established joint mining rules to ensure Maine’s natural resources would not be damaged.

“The big dog in the fight was groundwater standards,” said Stebbins.

These 1991 joint mining rules required mines discharging water to meet state groundwater standards and reflect natural background levels. Pro-industry voices saw the rules as practically a ban on mining in Maine; some companies that had been conducting exploratory drilling lost interest.

In 2012, Republican Gov. Paul LePage reopened Maine for mining as part of his larger aim to “open Maine for business.” That April, LePage signed a bill to streamline mining permits in Maine and throw out the requirement for mining companies to meet the state’s groundwater standards, effectively allowing them to leach toxins into the surrounding waterways.

Though the bill that reopened Maine for mining was enacted in April 2012, it took legislators and environmental advocates five more years to agree on how to adequately regulate the practice.

Pro-mining voices wanted mines to add jobs to areas struggling to retain residents. Those opposed to mining were concerned with protecting water resources from irreversible environmental damage.

“It’s just not worth it,” said former Sen. Brownie Carson (D-Harpswell), who led the NRCM for 27 years. “The long-term costs far outweigh the short-term benefits of having weak regulations and allowing mining interests to cut corners.”

Carson, the NRCM and other groups concerned with loose mining regulations introduced a bill in 2017 that would implement what may be the most protective mining laws in the country. Its passage in 2017 settled the legislative deadlock by repealing and replacing the 2012 bill with requirements similar to the pre-LePage level of strictness, but with some compromises given to pro-mining groups.

More than three years later, Wolfden is the first company to attempt to open a mine under those new regulations.

‘A very high threshold of environmental protection’

One compromise that came out of the 2017 bill dealt with meeting state groundwater standards. Recognizing that groundwater quality will inevitably be impacted by mining, the legislation freed companies from meeting Maine’s strict groundwater standards within 100 feet of a working mine.

“You can’t just mine and not change groundwater quality,” said Robert Marvinney, who has worked for the Maine Geological Survey for 34 years and served as its director for the past 26 years.

Marvinney said Wolfden would be required to monitor the 100-foot area and meet strict state groundwater standards outside the discharge zone to comply with DEP regulations. The requirements come on top of state rules prohibiting the discharge of treated water into small streams and vulnerable waterways.

“It’s a very high threshold of environmental protection,” said Marvinney.

The 2017 bill “came out of lots and lots of mines all over the country and the world,” said Bennett of the NRCM. “We’ve seen mines all over the country and the world that require active treatment in perpetuity after they close.”

In addition to banning mines that require indefinite treatment, the rules prohibit toxic mining byproducts to be buried underground to prevent the materials from leaching into groundwater; ban open-pit mines like the project Irving proposed at Bald Mountain; and require companies to prove their financial viability by setting aside money to cover the cost of “worst-case mining disasters,” and avoid taxpayer cleanup.

“This law was saying to mining companies, if you want to come mine in Maine, you better know what you’re doing and have the financial backing,” said Bennett. “(Wolfden is) exactly the kind of company this law was designed to prevent from coming to Maine.”

Wolfden anticipates paying a $13.7 million deposit to the DEP for a “worst-case” scenario if its rezoning and mining permits are approved. The LUPC questioned this figure on Thursday, saying it “appears low.”

Those opposed to mining pointed to past disasters that cost taxpayers millions to clean up — like the Callahan mine in Brooksville and Kerramerican mine in Blue Hill. Both were legacy mines operated by out-of-state interests producing metal concentrations that eventually created acid waste, and still require monitoring of polluted groundwater and soil.

The Callahan metal mine is a Superfund site still being remediated that will cost taxpayers roughly $45 million, and the Kerramerican mine, also known as the Black Hawk Mine, cost $9 million to clean up. Both mines predate regulatory agencies like the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and the Maine DEP.

Due to the lack of environmental protections back then and the fact Maine has adopted “the toughest rules in the country,” Marvinney of the Maine Geological Survey said comparing the old mining operations to current mining proposals is “unfair.” Those mines opened under “a very different, almost nonexistent, regulatory framework,” he said.

Wolfden’s plan

Wolfden’s goal is to extract ore minerals — including copper, zinc, lead, gold and silver — from a massive sulfide deposit near Pickett Mountain. The company would produce a metal concentrate to sell to international smelter companies that would melt down and separate the metals to provide materials for a range of uses, from sunscreen and toothpaste to medical devices, ships and money.

The Pickett Mountain mineral deposit was initially discovered by Getty Mining, a division of Getty Oil, in 1979, and was further explored by Chevron between 1985 and 1989. Wolfden purchased the land in 2017 for $8.2 million and has been test drilling for the last nine months.

The test drilling includes exploration around the known ore deposit, which the company values at $1.2 billion. On Jan. 11 and Dec. 8, Wolfden reported that test drilling found previously undiscovered mineral deposits it hopes to mine in addition to the deposit discovered in the late 1970s.

“We always anticipated it was there, but there’s going to be more than we originally thought,” said Ouellette, Wolfden’s vice president.

Wolfden bought the rights to do this type of exploration drilling at its Big Silver site in Calais but has not shared detailed plans with the public.

At the Pickett Mountain site, Wolfden plans to blast 32-foot wide and 16-foot tall tunnels underground that are big enough to fit trucks, according to documents submitted to the LUPC and interviews with The Maine Monitor. After extracting the material, the company would separate the valuable ore from the non-valuable leftovers, called tailings.

Wolfden has proposed an on-site ore processing facility that will prepare the ore to be trucked off to smelter companies.

Wolfden’s proposal also includes an on-site tailings facility where water is squeezed out of the toxic tailings to produce a moist, flour-like substance that will be stored in humps just above ground, in line with DEP regulations. When the mine closes, the humps — called tailings ponds — will be covered in grasses and shrubs as part of the reclamation process.

Environmental risks

Some of the most irreversible damage mining causes happens when toxic reactions take off on mining sites and have to be managed indefinitely. The extraction process Wolfden proposed raised concerns from environmental advocates and groups that have worked to keep the irreversible impacts out of Maine.

The biggest concern is heavy metal pollution through a process called acid mine drainage. This process happens after ore is ground up into powder and combined with chemicals that separate the valuable ore that will be shipped off and sold from the toxic tailings that are stored on top of the land.

The crushed rock waste that is stored in the ground poses a risk to groundwater resources because when ground-up rock rich in metal and sulfur is exposed to water and oxygen, acid is born, microbes multiply and the material becomes toxic. The process contaminates drinking water, kills aquatic organisms and causes damage downstream as heavy metals like copper, lead, arsenic and mercury bioaccumulate.

“There’s always risk. The grinding up (of) rocks makes them much more reactive and it’s not necessarily something that you can control after it’s been done,” said Dr. Jean MacRae, a professor of civil and environmental engineering at the University of Maine.

The balloons of toxic rock material will be sealed in two layers — an outside layer of clay and inside layer of polyethylene. MacRae called the plan a “belt-and-suspenders” approach to toxic tailings management but raised concerns even with the safety net.

“Mines are extremely dangerous to the environment,” said MacRae. “There’s no foolproof (solution). There will be potential for failure of any of these engineered solutions.”

Also, Wolfden’s water treatment plan — which informs the background levels the company must meet to discharge treated wastewater back into the ground at better or equal water quality levels of nearby lakes and streams — appears incomplete, said Dr. Stephen Norton, professor emeritus at the University of Maine’s School of Earth and Climate Sciences. Norton said background surface waters were sampled only once during the driest time of 2018 and methods weren’t included for review.

Norton also said pH, “the most important parameter for metal mobility,” was not reported, and other water quality parameters that help buffer or neutralize acid “were inconsistent and likely incorrect.” Norton said he hopes these problems will be resolved during the two years of detailed studies the DEP requires to determine baseline environmental conditions that inform the natural background levels companies must meet.

Indigenous concerns

As the rezoning process continues, concerns about the external costs and loss of ecosystem services that come with unplanned pollution from industrial processes like mining remain crucial to groups like the NRCM and Maine’s indigenous communities.

Dan Kusnierz, longtime water resources program manager for the Penobscot Nation, said the proposed mine could threaten culturally sacred waters that provide sustenance fishing rights to the tribe, including Grand Lake Matagamon, Mountain Catcher Pond and the Penobscot River.

“That area is really important to the health and wellbeing of the tribe,” said Kusinerz. “People go in those areas to hunt and fish and gather medicines and lots of other cultural(ly) important activities.”

Theresa Secord, a former geologist with the Penobscot Nation who sat on the land use committee that preceded the LUPC, said that while she’s concerned about the impacts on Maine’s environment, modern society “can’t live without mining.”

“Where do these places belong is the bigger question,” she said. “And do indigenous people in other parts of our hemisphere — are they the ones that are supposed to pay the price?”

Mining operations have polluted the sacred waters and lands of other tribes across the country, the Penobscot Nation’s chief warned the LUPC.

“There’s not going to be any clean mine,” said Secord. “Eventually, there’s the potential for something to happen. And if it doesn’t — still, there’s going to be tailings ponds and people are going to have to tend to that in perpetuity.”

Secord, Kusnierz, and Bennett of the NRCM are concerned about water resources being tainted in the process.

Bennett said there are no examples of mines that have injected treated water back into the ground that parallel what Maine requires. Other states have looser restrictions or larger bodies of water that can dilute the injected material.

“If you can’t prove the concept, if there’s nothing like this anywhere — and there isn’t — how can you say it’s a well-planned development? It’s not a well-planned development, it’s a wing and a prayer,” Bennett said.

What lies ahead

The LUPC is tasked with determining whether Wolfden’s project is “well-planned,” meaning that it is “technically feasible and financially practical.” Without the rezoning, Wolfden can’t apply for a DEP permit needed to start the production process.

Wolfden’s vice president hoped to address concerns over acid mine drainage and the company’s ability to meet Maine’s strict requirements for injecting treated water back into the ground down the line. But, the LUPC’s request this week will force more details to emerge in the next two months.

The LUPC’s request this week comes on top of continued pushback from Wolfden about the level of detail it must provide to the commission.

After the agency requested additional information from Wolfden during an Aug. 12 meeting, Wolfden’s lawyer filed an objection to the request on Aug. 26. The lawyer argued that parts of the LUPC’s request would be covered in its DEP mining permit application and asked the planning commission to “exclude” those areas from its analysis.

The LUPC said the information was necessary to process the rezoning petition and on Sept. 12, formally requested additional information from Wolfden. Stacie Beyer of the LUPC said that Wolfden “initially objecting to the level of information that we were requesting” was “unusual.”

Wolfden eventually complied, and will spend nearly $5 million on exploration drilling, and another $1 million between permitting applications to the LUPC and DEP in hopes of getting the metal mine near Patten up and running.

“We’ve sort of taken a leap of faith,” said Ouellette. “We know that we can operate this thing and make Mainers very proud of mining again.”

But the risks cannot be ignored, said MacRae, the civil and environmental engineering professor.

“I would not like to see something happening in this state where due diligence wasn’t done and groundwater became contaminated … It is a big job to try to fix something like this after the fact.”