Have you heard the one about the Mainer who drove to another country to charge his electric vehicle?

No joke. It happened last month to a fellow on a road trip from Falmouth to Aroostook County in his Tesla, after he couldn’t locate a Supercharger on his Tesla app.

He found one at a truck stop in Woodstock, New Brunswick, and crossed into Canada for a high-speed charge. At the border, the agent told him they get “regular inquiries” from Americans hunting for fast charging stations.

This Tesla driver isn’t a newbie. He has 200,000 miles on a car he calls the most carefree he has ever owned.

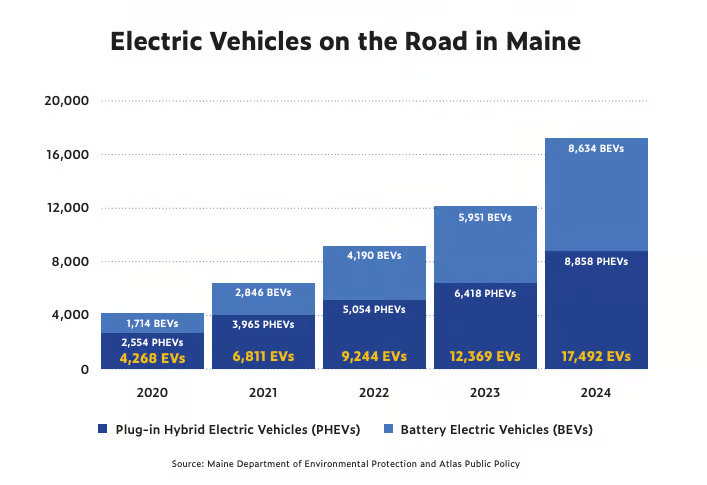

But his story is one of several anecdotes sent by readers reacting to an opinion piece I wrote two weeks ago for this newsletter, which was widely carried in other media. The column took issue with a goal in Maine’s newly-updated climate action plan of registering 150,000 electric passenger vehicles by 2030, even though there are fewer than 18,000 today, and only half are fully electric.

But the Tesla guy’s experience and other feedback I received left me with two impressions: First, Mainers feel strongly about how the state is promoting a transition to electric vehicles, with even some advocates acknowledging bumps in the road. Second, many Mainers — myself included — have good reasons to choose plug-in hybrids or straight hybrids.

And it left me with a question, based on today’s political and market realities. To best cut climate-warming emissions, should we double down on a so-far unsuccessful policy of trying to coax a wide range of drivers into battery-electric vehicles, or promote a range of lesser solutions that are more popular with a greater number of people?

The idea of anything but an all-in strategy was panned by a leader of one of Maine’s largest renewable energy firms.

“Yes,” he wrote, “Maine’s EV plan may be overly ambitious, but this is what is needed when you are contending with the multi-billion dollar colossus that is the global fossil fuel industry.”

I reached out to the Maine Climate Council, to see if the expected pullback from clean energy policies and electric vehicle rebates by President-elect Trump might influence the goals. Conceding the election has “serious consequences for climate action,” a spokeswoman noted the goals rely on comprehensive modeling that incorporates a range of factors, including the availability of rebates.

“The EV goals that the Climate Council has set for Maine are ambitious but realistic,” she wrote.

A major automobile dealer who promotes electric vehicles disagreed. It will be a “tough slog” to hit even 20% of the 150,000 goal, he suggested. A representative of used car dealers noted that Maine is among the nation’s most rural states with one of the highest costs of living. And it has more used car dealerships per capita — not the best environment for selling new electric vehicles.

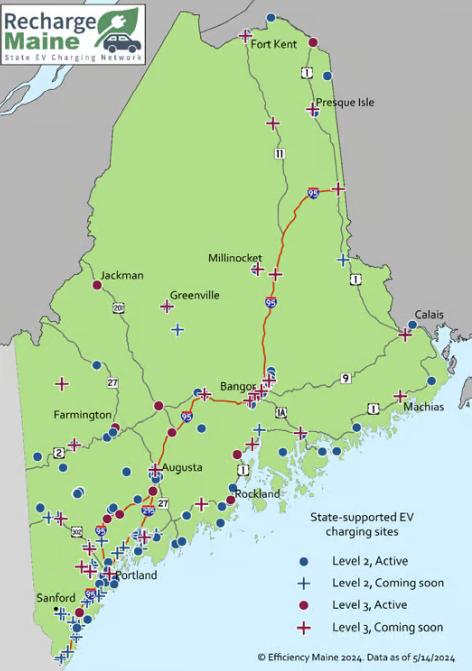

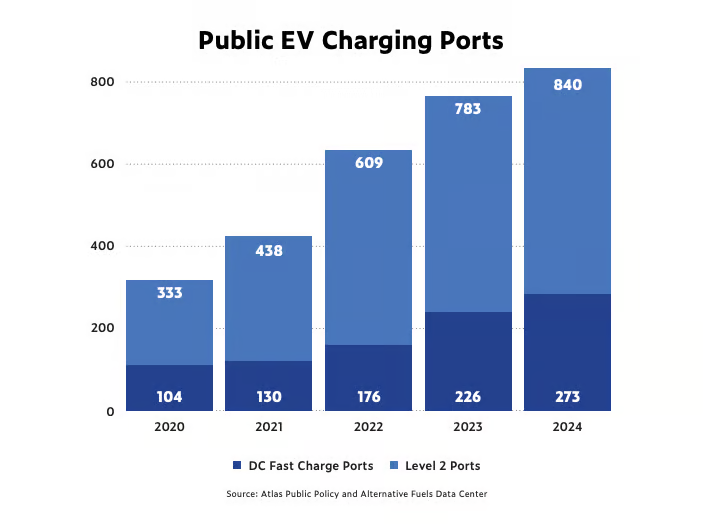

But mostly I heard from regular folks, who cited inadequate public charging infrastructure as a leading obstacle. The climate plan calls for installing 400-plus publicly-funded ports by 2028.

But a big chunk of the money to date has come from the federal government, and it’s unclear if President-elect Trump can or will seek to claw back future spending.

A climate activist from York wrote to say she had to take a taxi from the nearest charging station to a meeting at the Augusta Civic Center.

“I love my Mustang Mach e but its 285-mile range doesn’t even get me to Augusta and back for one of my climate meetings,” she wrote. “WE NEED MORE CHARGING STATIONS EVERYWHERE. They should be as common as gas stations if we expect people to use them as their principal, or only, car.”

A shout out for plug-in hybrids came from a mom from Standish, who says she loves her Toyota RAV4 Prime. She commutes 20 miles and can go 46-50 miles on a charge. That allows her to get to work and back and run an errand or two. In 19 months, she filled the car with gas four times, once for a trip to Connecticut.

“I would buy another plug-in hybrid after this,” she wrote. “…I love that when we are out and about we can have a change of plans and not be worried about needing a charge, finding a charger, etc. We can do what we need to do.”

Of course, plug-ins only cut emissions if their drivers are religious about plugging in. That’s not everyone.

“Our Portland neighbors bought a PHEV and in three years never once plugged it in, despite having their own detached house and driveway,” a reader wrote. “Not worth the bother to them.”

Some Mainers just can’t find a convenient plug where they live.

“I live in a ‘workforce’ condo development without assigned parking,” a woman wrote. “I have friends who rely on city street parking and friends who commute an hour each way to their jobs. Hybrids like the Prius work great for us. It’s been driving me nuts to listen to folks touting plug-in electric as the best single (ultimate) solution instead of considering conventional hybrids as a first step.”

That theme was expanded on in comments by a Portland Press Herald reader. They were responding to the strategy of targeting electric vehicle incentives for long-distance daily drivers who burn the most gasoline, the 9% of Mainers classified as Superusers. The reader, who has an electric vehicle and two conventional cars, said a typical EV lacks the range to satisfy a Superuser.

“They would run out of battery before they got home each night, if they are not routinely pulling up to an expensive Level 3 charger. For this group hybrids are currently the only sensible alternative. Even a plug-in with a 40 mile range wouldn’t move the needle with Superusers.”

Finally, there’s a little-discussed factor making Maine’s goal unrealistic in the short term — gasoline prices. They’re way down. Not to trash talk cheaper energy, but interest in electric vehicles ebbs and flows with the price at the pump.

Average gas prices in Maine surged to a record $5 a gallon in 2022, after Russia invaded Ukraine. Everybody wanted an electric car then, but supply chain kinks led to low inventories and premium prices.

Gas averages $3 today, and Trump’s oil-friendly policies aim to keep prices down. There’s a glut of electric vehicles now, but many cash-strapped Mainers may just decide to keep their gas guzzlers for the time being.