Fall is in the air, though we have a couple weeks left of astronomical summer. It’s a transitional time not just for our wardrobes, schedules and outdoor activities, but for the climate.

We know that the overall warming trend of human-caused climate change is reshaping and shifting the timing of our seasons — all anchored around the fastest-warming season, winter.

The shortening cold season, with fewer days of snow cover, is reflected in later falls and earlier springs — affecting plants and animals, the water cycle, outdoor recreation, energy use, infrastructure and more.

Here’s some evidence: The state climatologist’s office reports Maine has seen above-normal temperatures in September (where “normal” is the 21st-century baseline) almost every year since the late 1990s, with a peak at 6.9 degrees Fahrenheit above normal for September 2015.

Last fall was one for the record books — September 2023 was 5.9 degrees above normal (second only to 6.9 degrees in 2015), and October 2023 was 7.3 degrees above normal (behind 7.7 degrees in 2017).

We also wrote in this newsletter a couple years ago about record November warmth. Remember that week around Election Day in 2022 when the weather was much like it has been in Maine this week?

Federal data shows that the fall season has warmed the most in Maine after winter, unlike in many other states, where spring or summer are second in line.

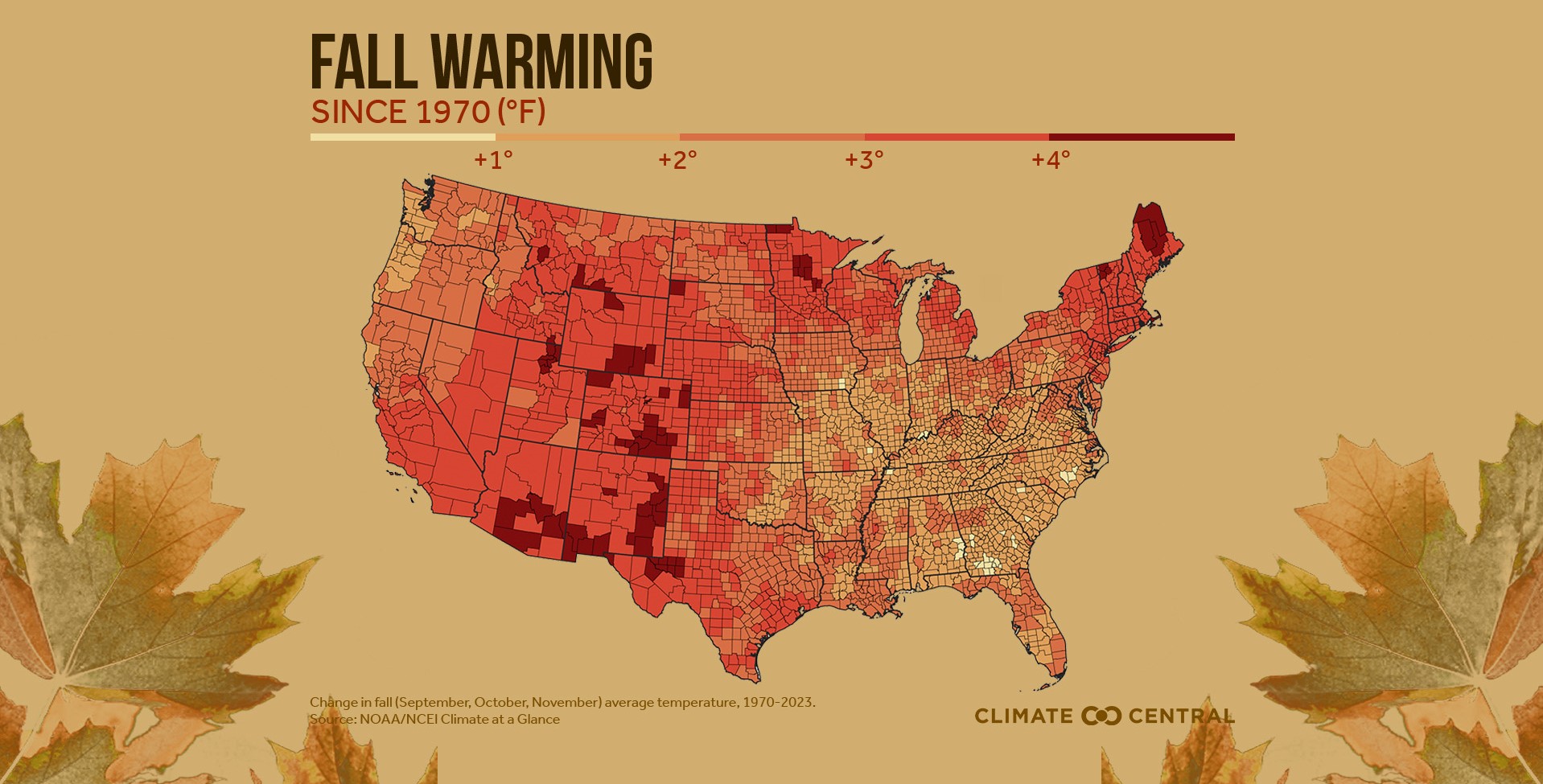

National data analyzed by the nonprofit Climate Central shows that the average fall temperature in parts of Maine has increased by about 3 to 5 degrees since 1970, more than the national average.

The analysis found fall warming in 97% of the 242 locations they studied, with increases above 3 degrees in a third of those places. The fall warming signal is strongest in the Southwest, and parts of Maine are seeing a comparable level of change.

Climate Central says that Portland, Bangor and Presque Isle are now seeing at least two to three more weeks' worth of above-normal temperatures each fall as they did about 50 years ago. ("Normal" here is the 1991-2020 baseline.)

A few degrees of warming might not seem like much. But ecosystems — including their human inhabitants — have evolved to respond in complex ways to minute changes in temperature, light and other factors. A small shift in climate can have big ripple effects, and we're only at the start of a long-term trend.

Among the impacts for people: more energy demand for cooling, including at the start of the school year in buildings that may be ill-equipped to provide it; a longer and more intense allergy season; and more smoke from deadlier wildfires drifting cross-country in hotter weather, increasing respiratory risks.

Warmer falls, winters and springs are also a boon for disease-carrying ticks, which can emerge earlier and feed longer in milder temperatures.

One climate impact that's less clear is on fall foliage. The factors that affect its timing and color are complex. Some aspects of warming cause leaves to drop later, but droughts can have the opposite effect.

Scientists know more about how climate change is affecting signs of spring — leaf-out, bird migration and more. More research is still to come on the autumn side of the calendar, to determine not just how much this season is warming, but what that warming will mean for nature and the built environment.

Correction: This story was updated to reflect we are approaching the end of astronomical summer, not meteorological summer.