Muhidin Libah crouched to pull yellowed leaves off a vibrant green kale plant as a light October rain gently dampened his button-down shirt. Rows of tomatoes and peppers stretched out before him, stopping abruptly at fields of corn.

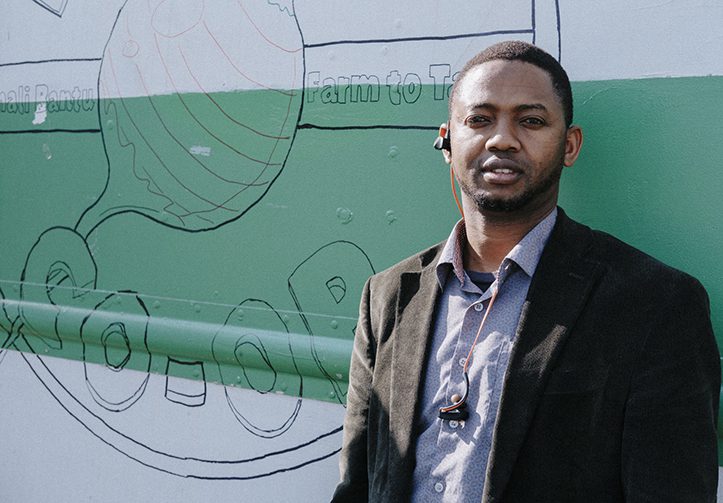

About 200 new Mainers grow vegetables on this 35-acre piece of farmland in Auburn as part of an effort from the Somali Bantu Community Association to increase access to healthy food and provide economic opportunity. With the arrival of the coronavirus, Libah — the executive director — said the organization’s efforts have become even more vital.

Long before the coronavirus, food insecurity was a challenge for Libah’s community in the Lewiston-Auburn area, where Libah said 90 percent of the roughly 3,000 Somali Bantu residents rely on food stamps. The pandemic brought additional challenges and heightened awareness of the problem — as it did for communities across the state — but creative solutions like this Auburn farm are expanding despite the current economic crisis.

RELATED: Preparing for a cold, hungry winter

Through a similar program, Sustainable Livelihoods Relief Organization, five families have gone one step further, preparing the vegetables they grew on another piece of land into traditional Somali meals they sell from a food truck. Festival cancellations this summer due to COVID-19 cost them an estimated $80,000, but they say they are moving forward.

“I don’t want people to think ‘They are immigrants. They don’t want to do the work. They will take state support and they are OK with that,’ ” said the executive director, Mohamed Dekow. “We are not OK with that. We are capable people and we have something to share.”

‘Food is the need that never goes away’

Libah grew his first plant — a mango tree — when he was 6 years old and living in southern Somalia. Decades later he aims to pass on his passion for farming to the next generation through the Lewiston nonprofit he co-founded, the Somali Bantu Community Association.

The Bantus are an ethnic minority group in Somalia that has a long history of farming and persecution. Libah said there is a “taboo” associated with farming in Somalia, but in Maine, Bantu immigrants have found success and pride through agriculture.

Farming is also a way to close the food insecurity gap. About 46 percent of Black or African-American children in Maine lived in poverty in 2018, according to data from the Maine Children’s Alliance. That’s down from 58 percent in 2014 but still three times the 2018 rate for non-Hispanic white children.

Food insecurity is a difficult problem to solve because it’s an ongoing need, said Mufalo Chitam, executive director of the Maine Immigrants’ Rights Coalition. And immigrant communities historically have unequal access to services.

“I say this over and over again: Giving somebody food is the need that never goes away,” Chitam said. “Because it is food that is consumed and then the next day there’s still that need.”

When families have their own piece of farmland, they can grow enough vegetables to last them through the winter, ensuring a renewable source of food as well as saved money for other expenses, Libah said. Numerous families have bought additional freezers to store the produce they grow, he said. And others saw decreases in medication or doctor visits because they ate healthier and had a more active lifestyle.

Researchers are exploring these types of effects on a national scale. While some have reported the potential benefits of urban agriculture on food security in the U.S., there is a lack of data on whether — and how much — the practice actually improves food security in low-income communities, according to a 2018 review by researchers from the University of California, Berkeley.

On Liberation Farms in Auburn, each participating family or individual gets about a tenth of an acre to farm. All the farmers pay is their time and effort. Some keep the vegetables they grow so they don’t have to buy them from a store while others sell their produce at farmers markets.

The vast majority of the farmers are women: “It is open to whoever is interested. It just happens that most of the people who are interested are women,” Libah said.

And the program continues to expand despite the pandemic. The Somali Bantu Community Association is ramping up corn production through a partnership with the Maine Grain Alliance and finalizing a 99-year rolling lease for 107 acres of farmland in Wales, roughly 10 miles away. They’ve had a number of short-term leases for farmland around the region, but all of those operations will consolidate to Wales over the next couple years. This new location also will include an area for goats, a wash station and a place for community events.

For someone who spent decades displaced, Libah says the 99-year lease represents a new sense of stability and security. He was about 7 when violence broke out in Somalia and his family fled. They eventually made it to Kenya, where he lived in multiple refugee camps over the next 20 years.

Libah settled in Maine in 2005 but it took him years to see it as a permanent home. That changed when he and others started putting down roots in farmland.

“When we felt a lot of certainty was when we started farming and people realized we are not going anywhere. We are in Maine; we are Mainers,” Libah said. “People started thinking about contributing to society, contributing to communities and improving the neighborhoods. Before, people thought it was another refugee camp: ‘I will be moving from this place.’ But now that we have farming, people started realizing this is it. We are not moving again.”

From farm to food truck

Across the Androscoggin River, in a Lewiston public parking lot that had been transformed into a farmers market, the smell of fried sambusas filled the air on a chilly Sunday morning. The co-owners of the Isuken Co-op food truck were busy preparing the vegetables they’d grown and mixing them with fish, chicken or beef to fill the crispy sambusa pockets.

Throughout the morning, they had a consistent flow of customers who also ordered items like sourdough flatbreads, vegetable soup and spicy Somali chai tea. Abdirashid Osman took orders while Ghali Arah prepared chopped vegetables and Habiba Hussein deep-fried the sambusas.

As they moved around each other in the tight space, all three explained, with Dekow translating from Somali into English, that the farming program connects them to their heritage and the food truck gives them a space to share with their broader community.

“(Number one, farming) keeps me sustained on my cultural heritage that my ancestors experience,” said Osman, who has lived in Maine for five years. “Number two, serving a community that I wasn’t part of. I want to serve them what I grow, what I know.”

The idea for a food truck was born through Sustainable Livelihoods Relief Organization, which has a similar operation to the farm in Auburn: 13 families each get their own piece of a 3.5-acre plot of land outside Lewiston. Farming provides a way around the language barrier that new immigrants often face when searching for employment, Dekow, the executive director, said.

The five co-owners took out a $30,000 loan to purchase the food truck in 2017. Last year their truck broke down so they hoped to hit the ground running this summer. But then 27 catering events were canceled due to COVID-19 restrictions on gatherings and Dekow estimates they missed out on $80,000 of revenue. They reopened later in the summer when the governor raised the limit on public gatherings to 100.

Arah said she hopes to show her children, through the food truck, the strength of collaboration and the value of seeing where their food comes from. On top of that, her work provides enough fresh food to last her family through the winter.

When she became a U.S. citizen, Hussein said she wanted to find a way to get off government assistance. She is eager to report an income that disqualifies her for food stamps.

“I wanted to see as an African-American U.S. citizen (if) I can be involved in small business (as an) entrepreneur, which I can leave behind to my family if I succeed,” she said.

Hussein typically starts her shift as a housekeeper at 5 a.m. and works until 1 p.m. After spending about two hours with her children, she heads to the farm around 3:30 p.m. and works until about 6.

Through farming, Hussein has extra food coming into her home, that “I grew,” she said with extra emphasis. “I cook the food that I grow that I put a lot of energy (into).”

The old food truck is dragging them down with numerous costly mechanical problems, Dekow said. Still, they already envision the operation becoming a brick and mortar restaurant.

At least one of their customers on a recent Sunday would like to see that happen: Shelley Reno of Auburn said she loves sambusas because they’re flavorful.

“I wish there were more restaurants like this around here,” Reno said.

Vanessa Stasse added that traditional Somali food like sambusas “are starting to be woven into the culture of Lewiston.”

“They’ve become accepted like grabbing hot dogs,” she said.

For Dekow and Libah, support for their programs is an investment back into the broader community.

“All we need is the opportunity — the playing field to improve ourselves. At the end of the day we will be taxpayers and part of the community,” Libah said. “ … We are ready to work, we are hard workers, all we need is to get a push.”