Editor’s Note: This fall, the Maine Climate Council will refine draft strategies into a Climate Action Plan due to the Legislature on Dec. 1. Sea Change columns are covering related topics – in this case, how the plan should address a potential influx of climate migrants. To read previous columns in this series, click here.

What do you do when the place you call home becomes unlivable? Tens of millions of Americans will face this wrenching choice over the coming decades as they contend with climate-fueled disasters such as wildfires, hurricanes, sea-level rise and unbearable heat.

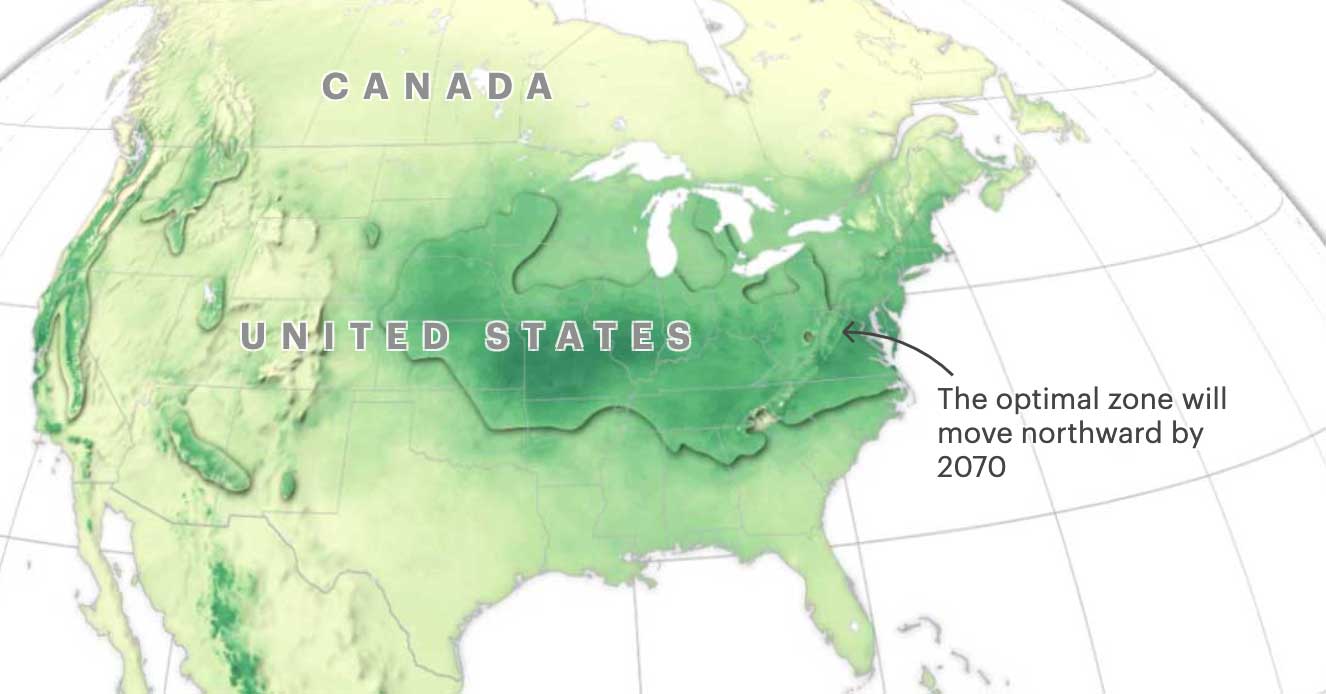

A recent New York Times/ProPublica report suggests that many uprooted Americans will likely move farther north. Judging from the influx of in-migrants since the coronavirus pandemic began, Maine may be a preferred destination.

Climate migration might seem like a distant prospect but already has begun.

A dream setting turned nightmare climate disaster

Laura Hinerfeld has lived in the wine country of California for nearly a quarter-century, raising two sons there with her husband Dale Geist, a musician, while working as an ICU nurse. They have strong ties to their home community of Sonoma, which she describes as a “very sweet town where everyone cheers for each other’s kids in baseball games.”

On a picture-perfect October weekend there three years ago, she spent both days outdoors under blue skies, thinking, “I can’t believe how lucky I am to live here.”

That Sunday night the winds grew ferocious, gusting up to 70 mph and blowing over their backyard fence. They could smell smoke, but the power was off and in the dark it was unclear how close the fire was.

The next morning they were advised to evacuate as the Tubbs Fire ripped through Sonoma and Napa counties – where it would eventually claim more than 5,500 structures. For days the family was in limbo, unsure whether they would have a home waiting for them.

Their house survived, but community members experienced “a lot of trauma and collective grief,” Hinerfeld said. Persistent drought made fire a year-round threat, provoking chronic anxiety: even wind now has “such bad associations.”

For two weeks last fall, hazardous smoke from the Kincade Fire prevented their family from going outdoors. Trapped inside, they rarely had electricity because the utility shut off power to prevent further fires.

This year, California’s fire season is breaking all records. In early September, a heat wave sent the temperature in Sonoma spiking to 116 degrees. At month’s end, Hinerfeld acknowledged that since Aug. 17, “it has been either too hot or too smoky to comfortably be outside for all but a handful of days. It’s extremely smoky everywhere, including inside now.”

Late in September, the Glass Fire tore through Sonoma and Napa counties – consuming 42,000 acres in its first two days, endangering communities 10 miles north of their home.

This time her family will not just grab go-bags for a temporary evacuation. They are packing everything and heading to Maine. Both Hinerfeld and Geist have family in the Northeast so the move here “feels like a homecoming.”

Yet even so, her family is heartbroken to cut ties with California, she said. After toying with the idea of returning someday, they had to confront the hard reality that “it will never be the place it was when we moved here … I consider us climate refugees.”

Where to go when disaster strikes

Many of their friends in California remain shell-shocked, Hinerfeld said, “just sort of adrift emotionally,” unsure where to go or what to do. “It’s really awful.”

When disasters strike, sociologists report that those who move typically stay in the region – often congregating in urban areas. Few scientists have begun looking at patterns of climate change migration, but initial evidence suggests they may not follow those norms.

“As these climate catastrophes become more frequent,” said University of New Hampshire climate scientist Cameron Wake, “people will be thinking more about places that are more climate-resilient.”

Human behavior is notoriously hard to model, and the choice to relocate often reflects some mix of push and pull factors. Hinerfeld and Geist, for example, had the pull of aging relatives in New England alongside the push of recurrent wildfires.

In a world beset by climate crises, no setting will offer refuge. When house-hunting in Maine, Hinerfeld was dismayed to see evacuation route signs. “What would I be evacuating from (here)?” she wondered. Maine holds fewer risks of smoke and fire, certainly, but flooding risks remain real.

The prospect of fresh water, in moderation, could draw climate migrants fleeing drought. And Maine has been “a summer getaway for millions of people,” Wake said, so those positive associations may lure climate migrants.

The coronavirus pandemic has brought an influx of urban refugees renting and buying homes around Maine, and even this modest increase is driving up housing and rental prices – exacerbating the state’s affordable housing crisis.

Hinerfeld and Geist were “taken aback by the competition” for housing, she said. They had hoped to settle in Maine this month but even when making bids well over asking price, they lost out on four properties.

‘High-level planning’ to revitalize Maine communities

The critical question becomes, in Wake’s words, “How do you turn what could be seen as challenging into something good for the state of Maine?” The answer lies in “high-level planning.”

Climate migrants could revitalize aging Maine communities, bringing an influx of youthful energy and tax revenues. Incentives could help in-migrants buy and retrofit older housing and commercial buildings in bikeable and walkable neighborhoods. Zoning for increased density, multi-family units and accessory dwelling units “should be front and center” in Maine’s climate plan, Wake said.

If Maine’s population swells with climate in-migrants, strong land use policies will be needed to prevent suburban sprawl. Maine is already losing an estimated 10,000 acres of farmland and forests to development each year, and that annual figure will likely increase to 15,000 acres by 2030 and 20,000 acres by 2050.

The Maine Climate Council’s draft proposed strategy framework cites the need to strengthen land use regulations, which Wake said will be key to keeping new construction out of areas vulnerable to flooding. The plan also needs to address the risks of climate gentrification, where in-migrants from more affluent areas could displace local residents.

An investment worth making to attract climate migrants

Several cities, such as Duluth, Minn., and Buffalo, N.Y., have recognized the opportunity for an economic and cultural renaissance, and are working to attract climate migrants and take steps to prepare for them.

Experts suggest that most climate migrants will likely settle in larger cities, but the pandemic may change that. With the rise of remote work and the expansion of broadband, people might prefer smaller communities and more accessible outdoor recreation.

If Maine deliberately planned for climate migrants, it would be the first state to do so, noted Jesse Keenan, an associate professor at Tulane University’s School of Architecture who consults with cities eager to welcome climate migrants.

Keenan tells communities to use that expected influx as an opportunity to invest in affordable housing, public transit and other upgrades that will improve quality of life and reduce carbon emissions.

More people will relocate to Maine, whether or not the state plans for them. By anticipating this wave, we can welcome newcomers while protecting the qualities that drew them here.