PARIS HILL – Sandy Bahre’s apprehension quickly gave way to terror that day some 45 years ago in New Jersey’s bleak pine barrens. A gaunt man with stringy long hair was walking from his house, which was more tar paper than clapboards. He held an axe in both hands, swinging it in front of him.

“He was mumbling, over and over, ‘the man from Maine, the man from Maine,’” said Sandy Bahre. “I turned and started running back to our car, crying I have two kids at home.

“It was like a bad movie.”

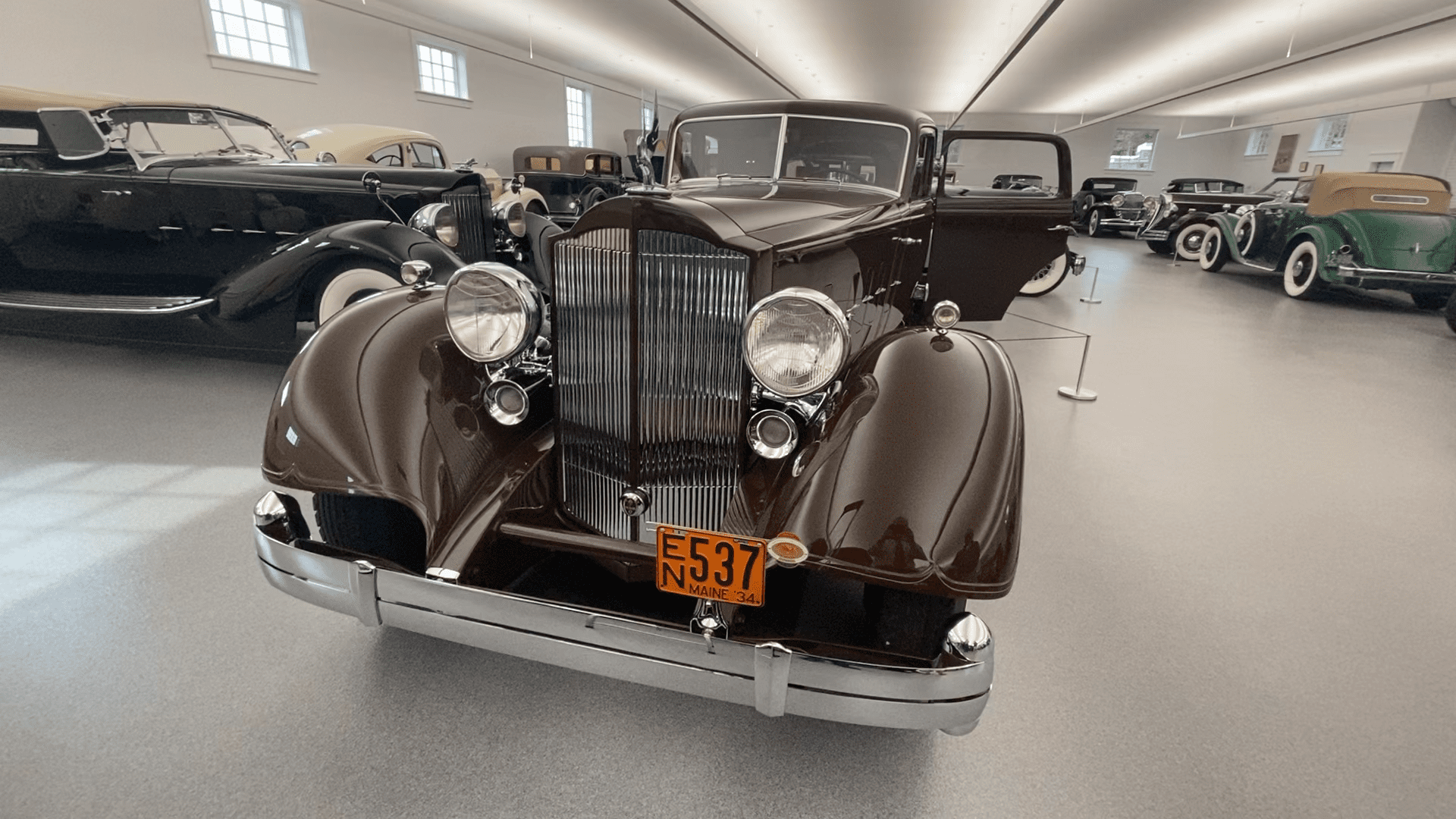

Bob Bahre, the legendary racetrack owner who died over the summer at age 93, turned to his wife, calling her back. They had traveled from Maine to see a 1929 Duesenberg J Convertible Coupe by Derham. Its owner was walking toward them with the axe. The car was across the road in a garage that was more a shed and in need of repair.

No one knew this would be the beginning of Bahre’s renowned collection of classic cars, least of all the man with the axe. Several years later, around 1978, Bahre started displaying his growing collection to the public. He charged admission with the proceeds benefiting the Hamlin Memorial Library and Museum next to the Bahre home on Paris Hill.

The event was called Founder’s Day. Bahre’s classic cars would be in the public eye for 42 years until the pandemic struck this spring.

RELATED: The Wonderful Life of Bob Bahre

“I just remember him as Mr. Parkinson,” said Sandy Bahre of the New Jersey man. “And that axe. Bob had heard about the car but Mr. Parkinson didn’t want to sell. Bob asked if we could just come see it and he agreed.”

Bahre had learned the hard way not to buy a collectible car unseen. He heard of an early Packard in Georgia and bought it without seeing it. And promptly resold it after it was delivered to Maine, its condition very rough. Bahre hadn’t yet hired the man and later the crew who would restore cars that sometimes arrived in pieces.

“I think, 90 percent of the time the cars were not for sale,” said Jeff Orwig, the curator of the Bahre collection. “Bob didn’t like buying at auctions. It was the hunt, the chase, the discovery. Then Bob would build a relationship with the owner after he saw the car he wanted.”

So it was with that first Duesenberg, a make that was prominent more than 100 years ago at Indianapolis Speedway. After World War I, Duesenbergs became the powerful beasts of American roads, driven by the wealthy.

Sandy Bahre remembers first seeing it buried under a pile of boxes and whatnot in the shed. The Bahres returned to Maine without any promises or even hope of buying the car. Bahre did get permission to return, just to see the car despite being told repeatedly it wasn’t for sale. But he kept in touch and soon was no longer simply ‘the man from Maine.’

“We found out Mr. Parkinson liked the Appalachian Trail, so we drove to the trail here in Maine and took pictures,” said Sandy Bahre. The photos were mailed to Parkinson.

Eventually, Bob and Sandy returned to New Jersey and Parkinson’s home with a large brown shopping bag filled with cash. Parkinson took the money and Bahre had his prize, the only Duesenberg convertible made by the coach builder Derham.

That was an era when some car manufacturers built the engine and chassis, and different coach builders built the bodies far from an assembly line. They were expensive, and after the stock market crash of 1929 and the start of the Great Depression, fewer were made and sold. Only 200 Duesenberg J models were made in 1929, for instance; the company had planned to build 500. These became the cars Bahre sought.

At first Bahre didn’t intend to build the collection of more than 60 cars in his family’s possession today, many of them highly prized. He did thoroughly enjoy, as Orwig put it, the hunt, the chase, the discovery.

“He loved the cars no one knew about,” said Gary Bahre, his son and self-described sidekick. “My father loved buying cars people didn’t appreciate at the time. He had the foresight to know what to buy,” believing they would appreciate in value. These were his Van Gogh’s or Frederick Remington’s.

In an oft-repeated quote, Bahre told a writer for the Robb Report in a 2013 story that, “Some guys chase broads, I chase cars.”

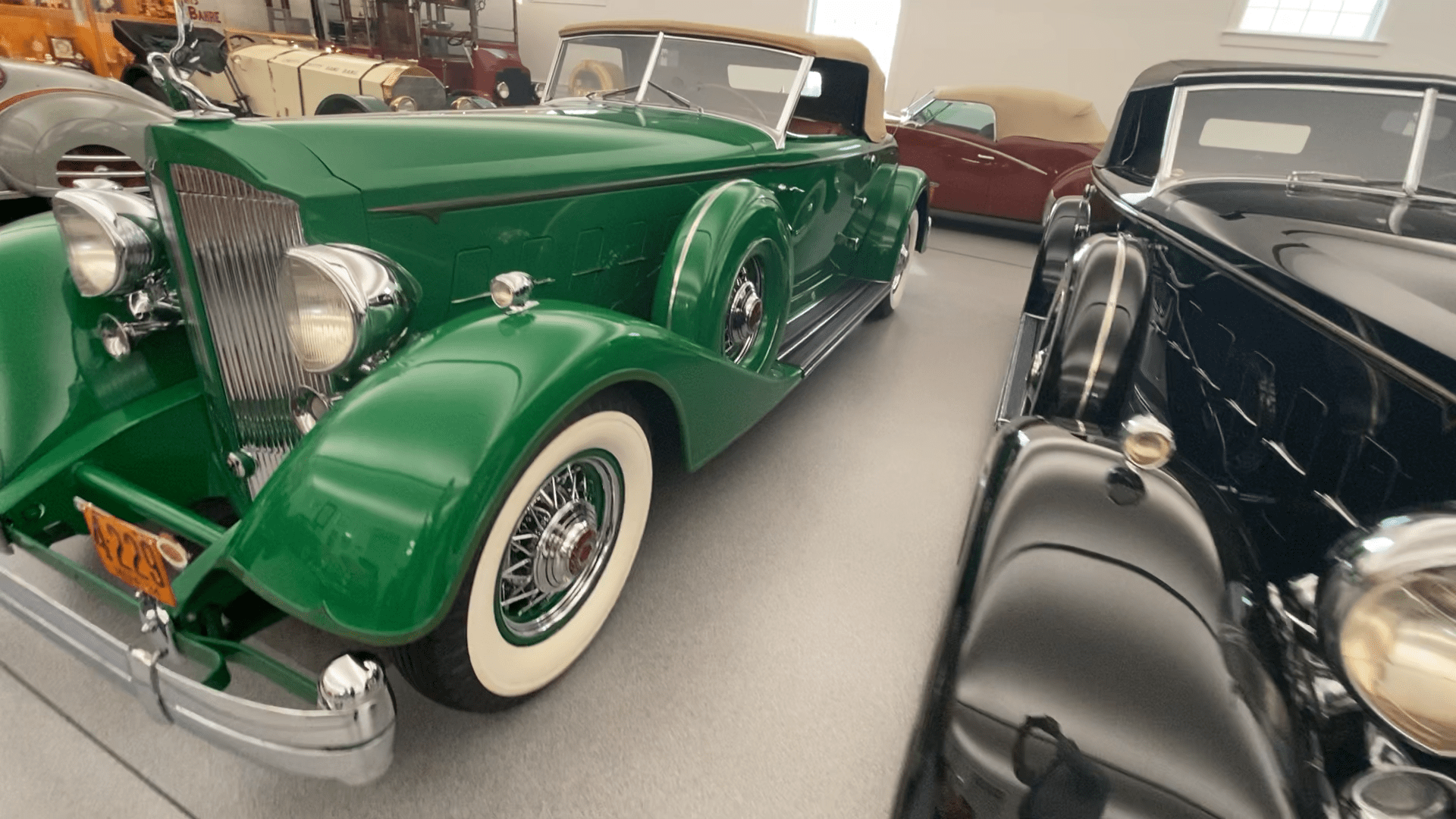

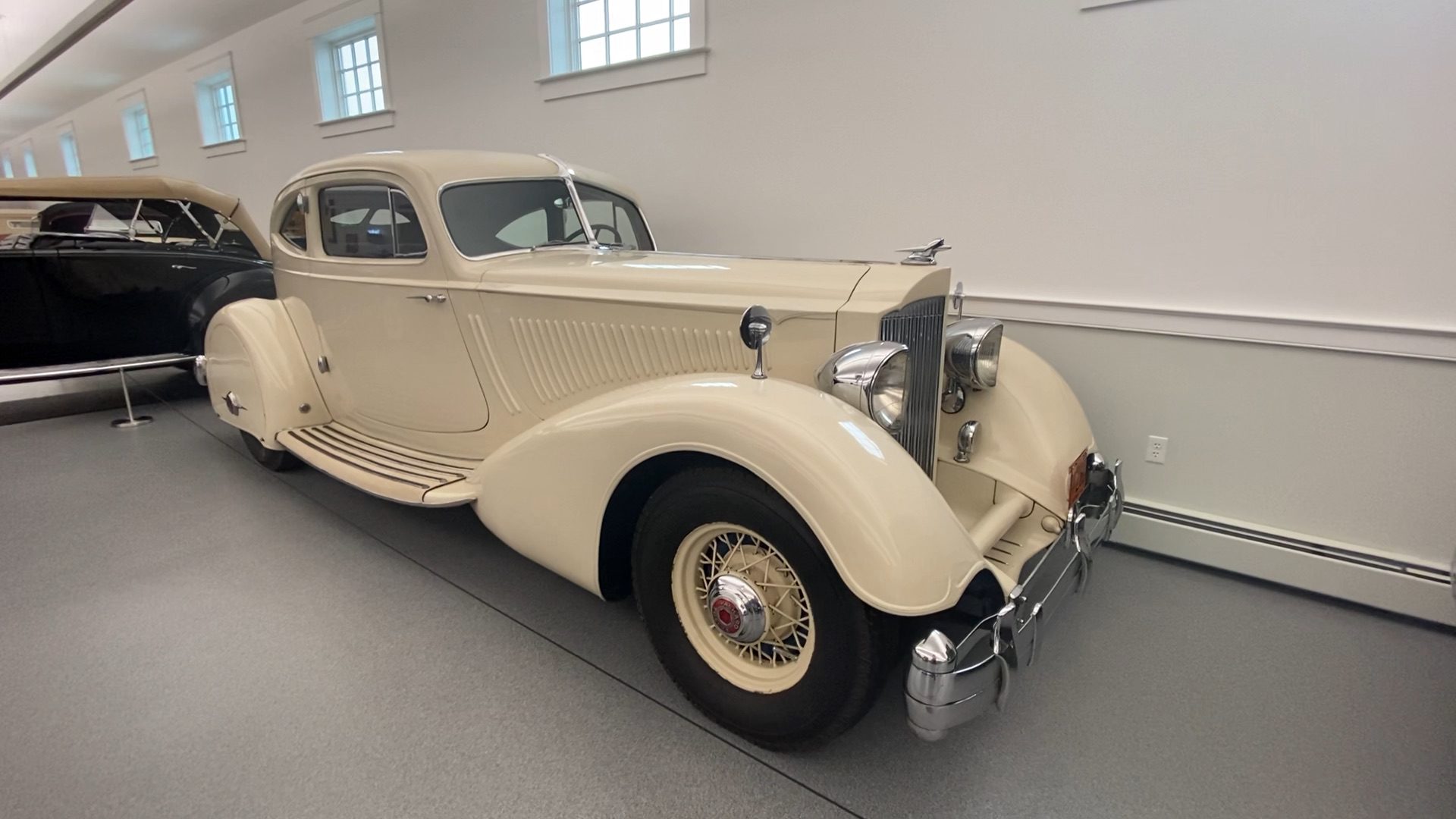

Sandy Bahre tells the story of her husband getting a call from the owner of a Packard Twelve Convertible Runabout by Dietrich, a car coveted by collectors. The man lived in Lakeland, Fla., and wasn’t interested in selling, but was intrigued by Bahre. The owner called one day, asking Sandy and Bob to lunch. In Florida. A bag was packed, flight tickets were booked and the Bahres were in Lakeland in time for lunch.

“We went to a Steak ‘n Shake for hamburgers,” said Sandy Bahre. “The car was never discussed. Bob wasn’t going to bring it up. We finished lunch, we agreed we all had a nice time. On the plane, Bob and I looked at each other. What was that all about?”

Some time later, the owner called Bob Bahre, saying he was ready to sell.

The hunt took Bahre to Michigan to see a 1937 Duesenberg J Convertible Coupe by Rollston that was partially restored. Its owner had run out of money to complete the work. Bahre was more than interested. Everything about the car was original, making it a rare find.

The owner didn’t want to sell, which Bahre knew. Bahre withdrew $500,000 in cash, or so the story goes, and put the money into carry-on luggage. When Bahre asked again about the car and again heard it was not for sale, he reached for the bag. And dumped all the money on the living room floor.

The owner’s wife interceded and took her husband to another part of the house. Bahre said he fell asleep on the couch, waiting. When the couple returned, Bahre got his car.

One of Gary Bahre’s fondest memories of his father was a trip to Kansas City, Mo., as a boy. “It became a three-day trip. “My father was looking to buy a Dietrich Coupe. We both got haircuts at the airport barber shop, so that became known as my haircut trip with my father. It was very memorable. I loved being with my father on those trips.”

Being Bob Bahre’s son did come with perks. Bahre acquired a Jaguar XKE that became the car Gary drove after getting his license.

Bob Bahre didn’t drive the cars in his collection much. In fact, hardly at all. Sandy Bahre remembers trips to Fryeburg with their children in the rumble seat of a Duesenberg, but not many other occasions.

Bahre got greater enjoyment watching someone else behind the wheel, usually Orwig.

Various cars in the collection were entered in the Concours d’Elegance at Pebble Beach, Calif., or at Amelia Island off the Florida coast, or at Hershey, Pa. At Pebble Beach, a 70-mile tour along the coastal highway to Big Sur and back was a highlight, seeing the classic cars in action. Bahre got more enjoyment driving ahead, parking and watching his car drive by with Orwig behind the wheel.

Bahre’s cars won 12 Best in Class at Pebble Beach over the years although a Best in Show eluded him. True to his disdain for anything that might hint of self-promotion, Bahre refused to have his photo taken with his winning cars. “It’s not about me,” he would say to Orwig, who was at the shows, overseeing the cars’ transportation to the sites.

Orwig is a University of Pennsylvania graduate with a degree in mechanical engineering. He worked 33 years for Bob Bahre and remains employed by the family. There are no plans to dismantle the collection.

“Sometimes I’d look at Bob, the car collection and my job, and wonder, ‘how am I in this picture?’ I’ve been very lucky,” said Orwig. “Bob was a great man. He came from nothing. He was always grateful for the work you did.”

Which isn’t to say Bahre wasn’t demanding. “He was in the shop three times a day sometimes,” said Orwig. “In his work, all progress was visible. You found a piece of property, you bought it, you planned how to develop it and you developed it. With car restoration, progress wasn’t as visible. Sometimes he’d be away for a couple of weeks, come back and see the chassis was still stripped and ask what the hell we’ve been doing.”

Chris Charlton, the first of the men Bahre hired to restore his cars, grew up in Williamsport, Pa., where Orwig also lived, the son of an attorney who had a deep interest in classic cars, but not the budget to buy the most desirable. Orwig inherited that interest and went to work on cars. Orwig and Charlton were acquaintances and through him, Orwig found himself working for Bahre.

Years later, after Bahre was adding fewer cars and most of the restoration work was done, Charlton started his own restoration business in Oxford. Orwig stayed with Bahre. If Bahre considered the car collection his children, Orwig became its godfather. He is his own Google search engine, knowing the history of each car in the collection.

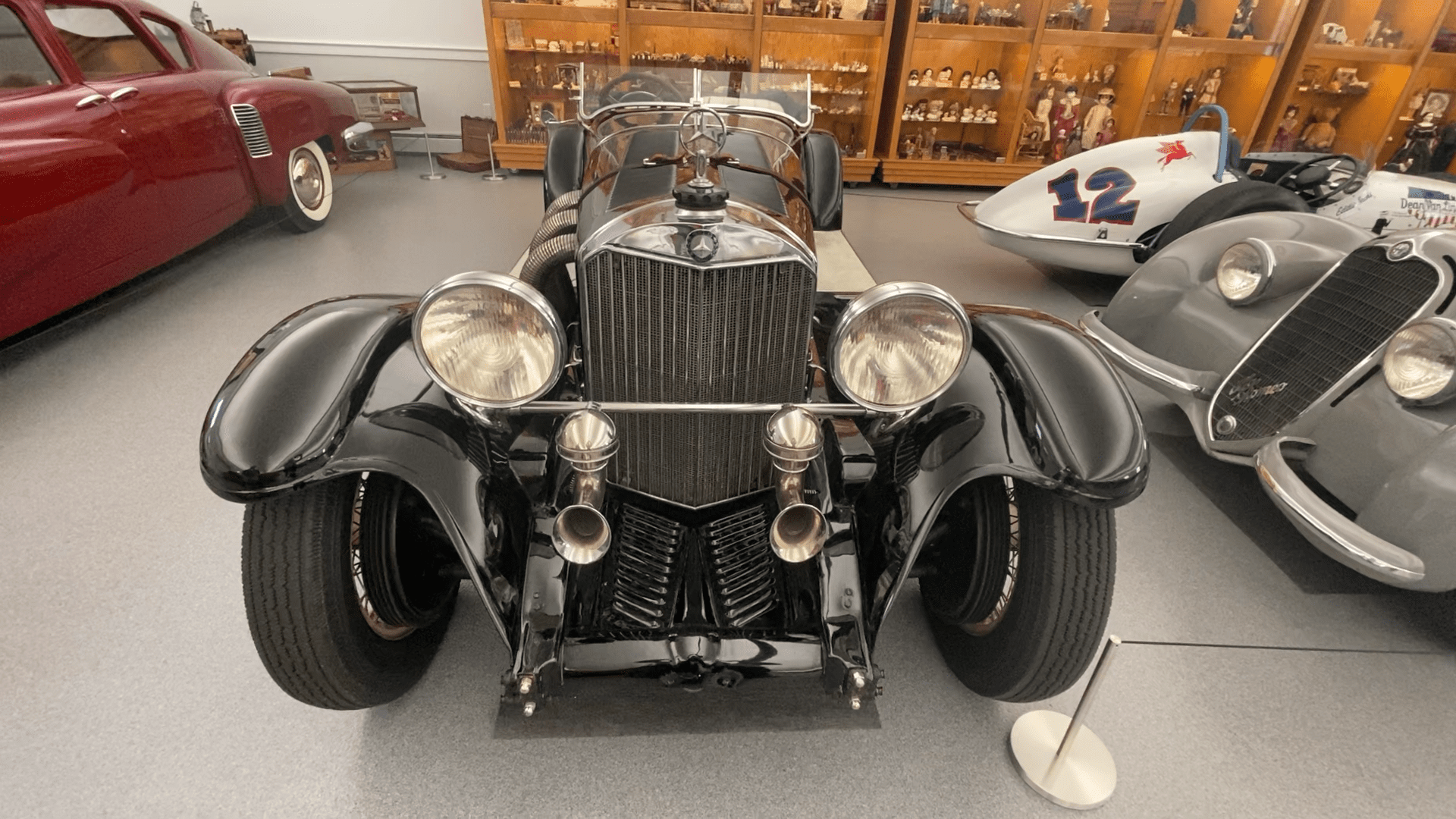

Mention to Orwig that the big, black Mercedes-Benz in the Bahre’s freshly renovated car barn looks like a World War II German staff car and Orwig begins the lesson. The car, one of fewer than 100 built, was purchased by King Haakon VII of Norway at a Mercedes dealership in Oslo, shortly before the Germans invaded. The king and his family fled to England.

Adolph Hitler gave the car to his conquering general, Nikolaus von Falkenhorst. After the war King Haakon reclaimed the Mercedes. On a wall adjacent to the car is a framed photo of the vehicle, top down, with Winston Churchill in the back seat. The former British prime minister was invited to Norway for a celebration and expression of gratitude for Britain’s support in the war.

Stand in front of the 1933 Rolls Royce Phantom II Henley Roadster and Orwig will explain it’s completely unrestored with only 34,000 miles on the odometer when Bahre bought it. It’s one of the nine with coachwork made by Brewster, an American company. A father gave it to his daughter for her college graduation. She never married, lived in Boston and drove it mostly to the family summer home in New Hampshire. Bahre was only its second owner.

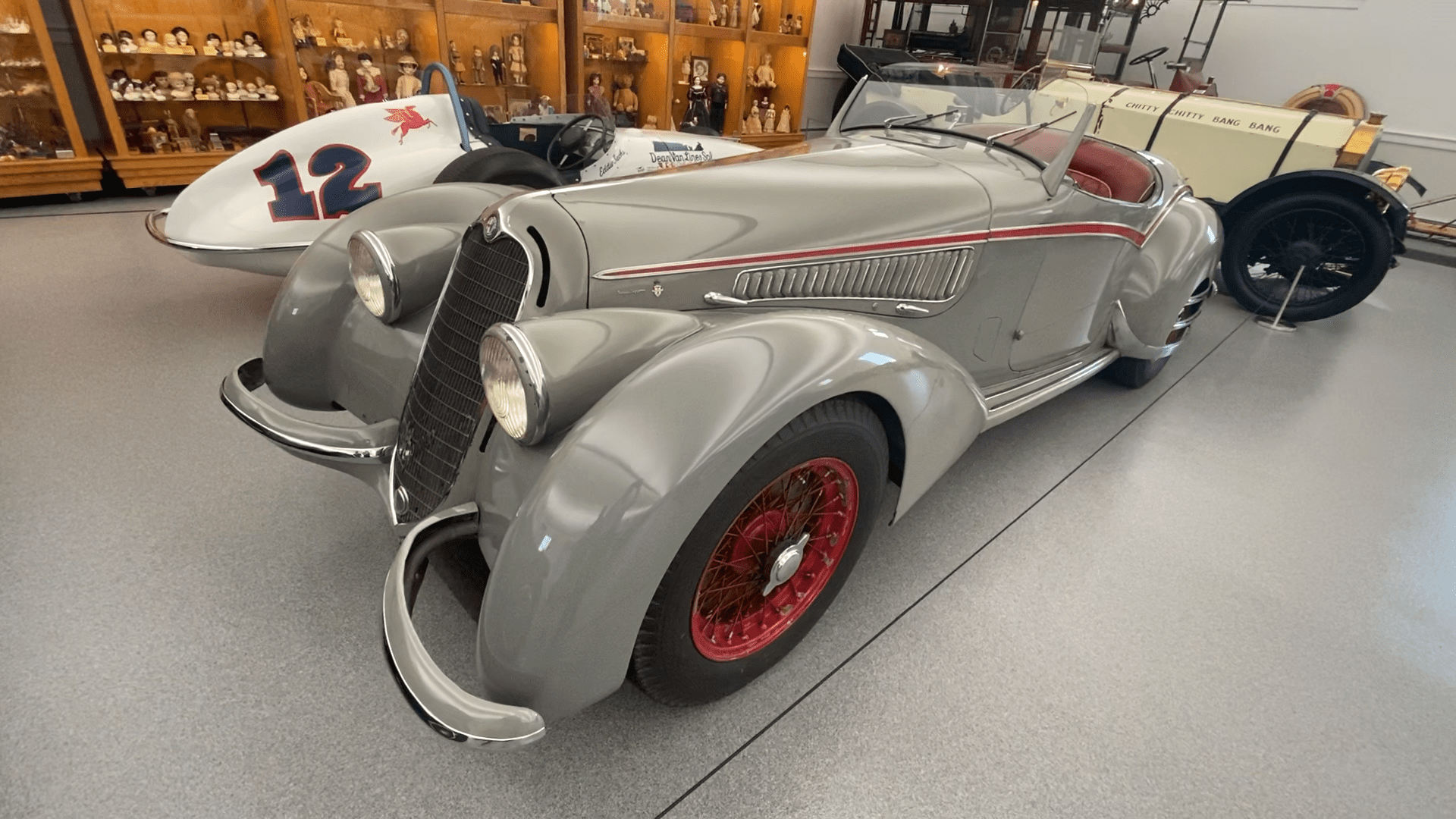

Bahre was one of the first collectors credited with realizing the value of unrestored cars in factory condition. Cars that weren’t “over-shined and over-restored.” Bahre once owned three of the 13 surviving Mercedes-Benz SSK sports cars, considered to be the fastest cars in the world with a top speed of 130 mph. A 1931 Mercedes-Benz SSK Sport II, is the one remaining in the collection. It is clean but original, cracks visible on its upholstery.

“His collection is world class,” said Peter Prescott, owner of E.J. Prescott, a waterworks distributor headquartered in Gardiner who was a minority owner with Bahre when New Hampshire Motor Speedway was built. Prescott had told Bahre that Bryar Motorsport Park in Loudon, N.H., was for sale and presented the idea that the property could be turned into a mile-long speedway for elite IndyCar and NASCAR races.

Prescott has his own car collection, mostly Ford coupes powered by Ford flathead V-8 engines, the type that went into many hot-rods. “Bob’s collection is a rich man’s collection. I have a poor man’s collection,” said Prescott, laughing.

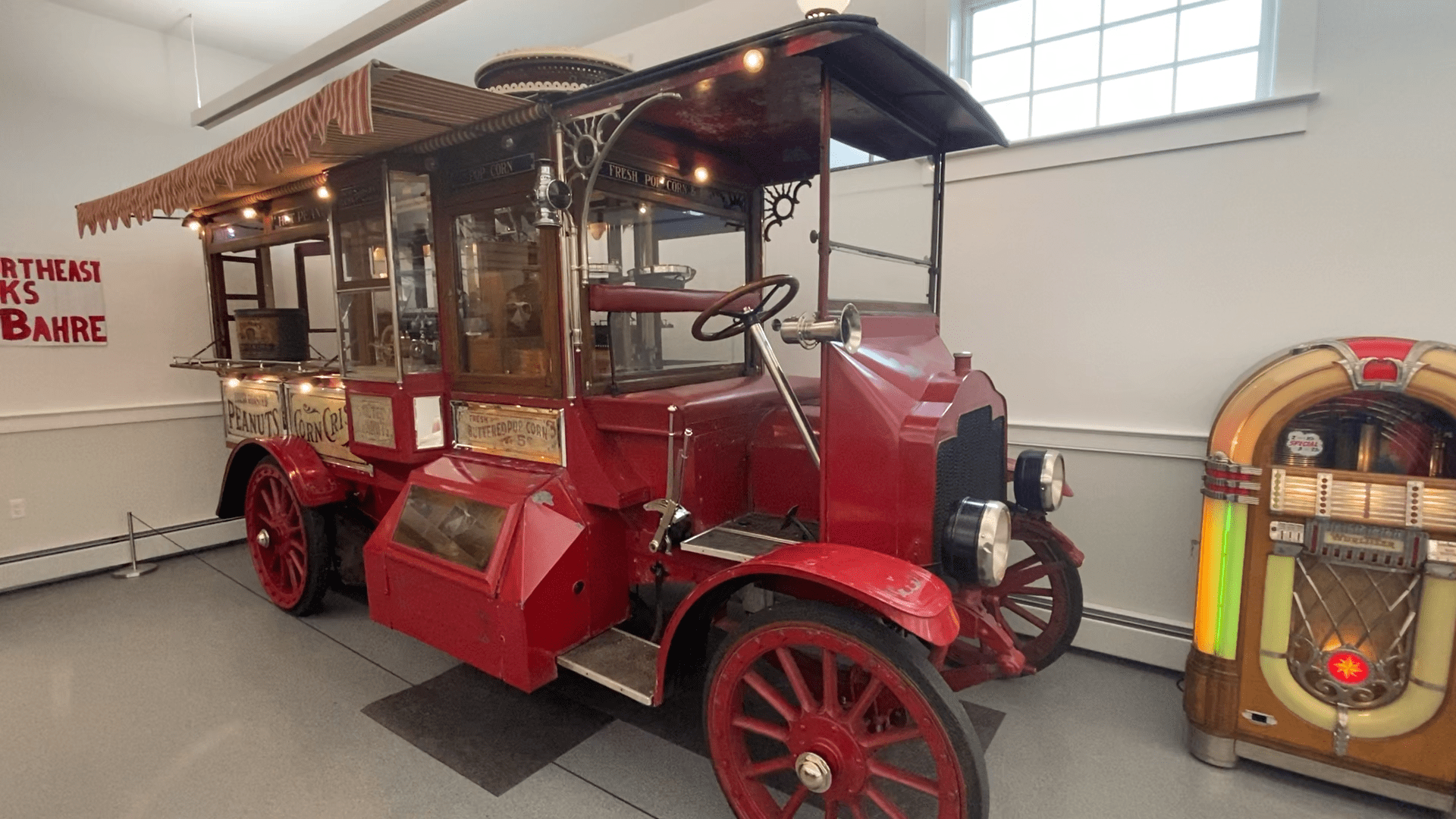

Years ago, Bahre had to buy an entire collection of cars from the widow of a collector associated with Silver Springs Park in Ocala, Fla. Bahre wanted a few cars from the collection but the widow insisted he buy them all. He did, selling off the cars he didn’t want.

Bahre sent a 1903 Prescott Steamer to Peter Prescott with a note. “You owe me $50,000.”

Bahre loved his family, loved his cars. “We’d go down to the car barn, sit on a running board and just talk for hours and look at the cars,” said Sandy Bahre.

Once, Bob Bahre showed the collection to a sports writer, explaining that he would walk in, turn on the lights and lie on the red carpet, propped up by an elbow. “If someone came in and saw me, they would think I was crazy and put me in the loony bin.”

He laughed.

More from Bahre’s collection