At the end of Joy Road in Fairfield, a steep dead-end road climbs a hillside to a scattering of homes with distant mountain views and some of the higher concentrations of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) the state has found to date in groundwater. The neighbors here live under what one resident, Nathan Saunders, called the “cloud of an unknown future,” fearing how PFAS exposure may erode their health.

Saunders and his family have lived in their home for more than three decades, drinking the water and irrigating their gardens until a state test for PFAS two years ago revealed appalling levels of these industrial chemicals, which can damage immune systems and harm many organs. An engineer by profession, Saunders charts the monthly test results of the water before it enters the granular activated carbon filtration system the state installed. Over 21 months, the raw water has averaged 14,067 parts per trillion (ppt) of six PFAS compounds, just over 700 times the state’s interim drinking water standard of 20 ppt.

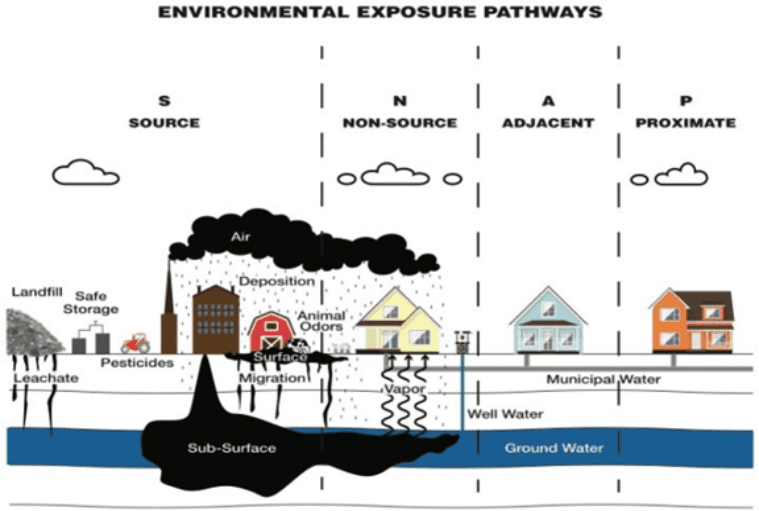

Across the street lies a former cornfield that received an annual application of what Saunders assumed was manure. It was in fact PFAS-laden sludge, according to the Maine Department of Environmental Protection. The DEP has confirmed that much of the sludge spread in the Fairfield area came from the Kennebec Sanitary Treatment District, which receives significant amounts of industrial wastewater from the Huhtamaki mill in Waterville, a manufacturer of Chinet paper plates, school lunch trays and other food packaging.

The sludge spreading stopped around two decades ago when the cornfield was subdivided into house lots. One of the homes constructed there was purchased early in 2020 by a couple in their early 30s, Ashley and Troy Reny. Later that year, the DEP informed them that their well water contained roughly 1,250 times the state’s standard for the six PFAS compounds tested.

Concentrated exposure

That news “put a huge monkey wrench in our life,” Troy Reny said. The two of them had gotten engaged and married on the property, and were looking forward to starting a family there. Those plans are on hold indefinitely as they cope with the chronic stress of living on what he terms a “dumping ground of poison.”

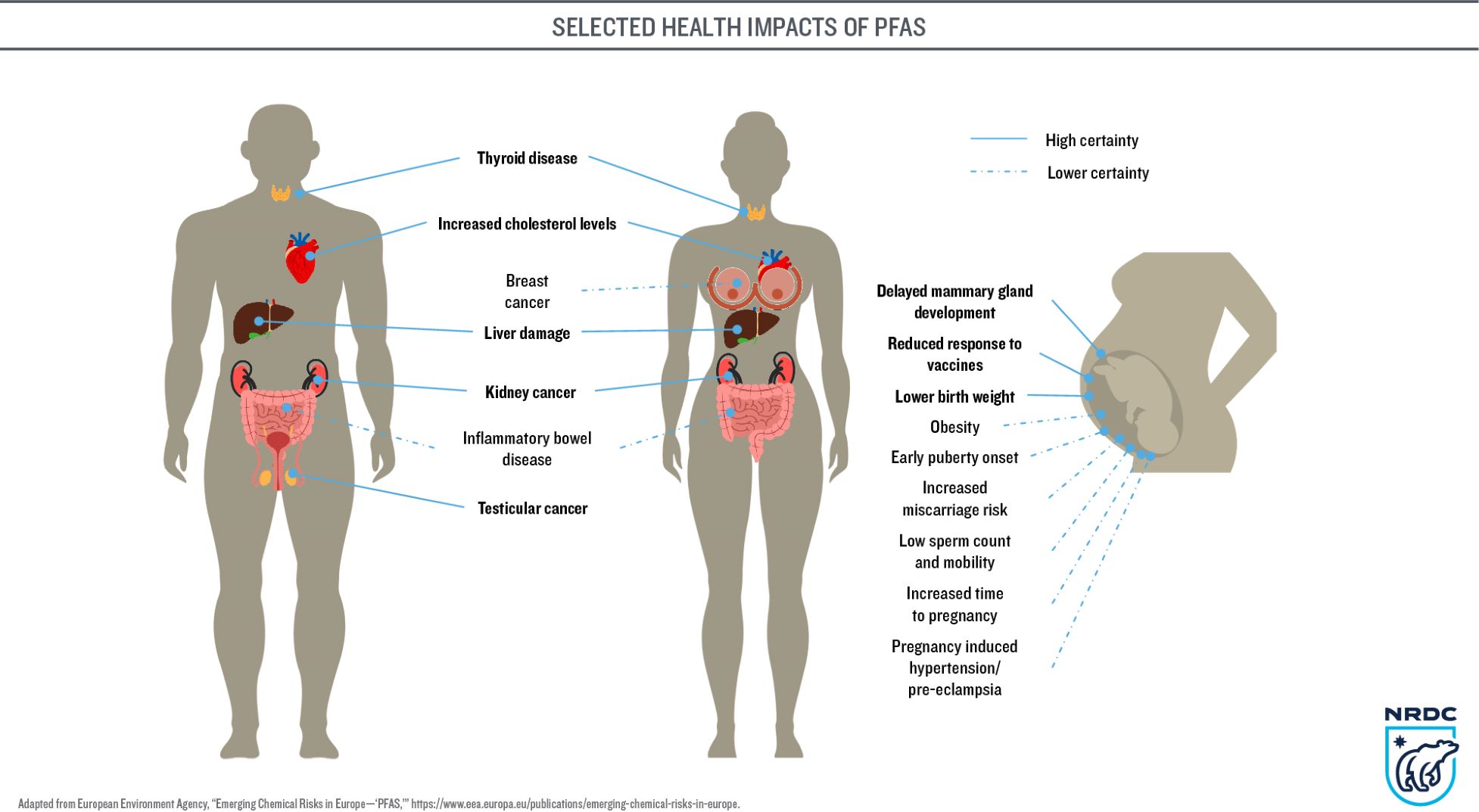

Part of the concern for those living in highly contaminated areas is that PFAS chemicals persist in bodies, dropping by half in blood serum only after a period of years — if exposure falls. If high PFAS levels in the immediate environment keep exposure elevated, the chemicals accumulate faster than the body can excrete them — raising risks of many associated health problems (see graphic). PFAS cross the placenta and enter breast milk so mothers risk passing the compounds they have accumulated on to their children.

A whole-house water filtration system does little to alleviate the Renys’ concerns about ongoing PFAS exposure. They worry that chemicals persist in their hot water heater, which was not flushed when the filtration system was installed. They drink bottled water, despite the added cost, because they know some PFAS break through as filters age.

For now, the state is maintaining the water filtration systems it has installed. Troy Reny said he’s pleaded to get filters replaced when any PFAS chemicals break through the final filter, but the DEP follows a set protocol, according to its spokesperson David Madore.

“Typically, carbon is replaced in the units when the between sample (water sampled between the two filter units) is about 10 ppt,” he wrote. “Data is evaluated on an ongoing basis to ensure that the after-filter system sample is below Maine’s standard of 20 ppt for the sum of six PFAS at all times.”

In June, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) decreased its lifetime health advisory level for two of those six PFAS compounds more than a thousandfold, to near zero, leaving the Renys concerned that the state standard is not protective enough. Once their system was installed, Troy Reny observed, “we were put on the back burner because this problem is out of control.”

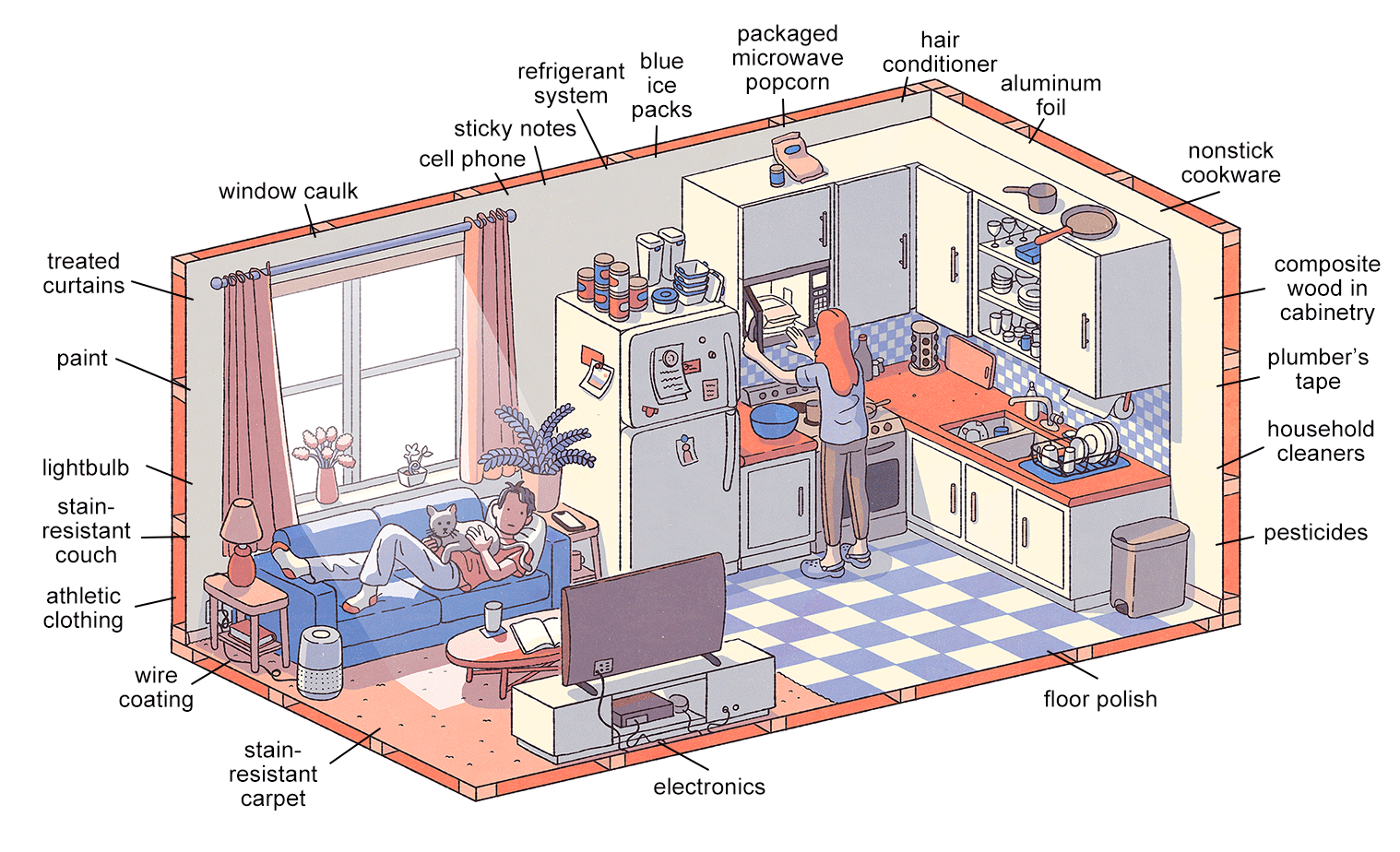

Suspecting their soil is contaminated, the Renys grow only a few fruits and vegetables, in planters on their deck. They worry about their dog, who can’t resist lapping at puddles in the yard. Knowing that grass readily takes up PFAS, they fear potential exposure from lawn-mowing. They are concerned about the toxicity of dust in their home, and the everyday products with unlabeled PFAS that could add to their exposure. Non-stick cookware and paper plates are now banished, Ashley Reny said; “I don’t want to be supporting those companies that are killing us.”

Water testing failed to flag the PFAS

In buying their house, she recalled, “we took all the necessary, all the right steps.” They ordered the state’s recommended water test for residential home sales and the results came back exceptionally clean. The test does not include PFAS, nor are the compounds listed as an add-on option.

The Maine Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) may reconsider its guidance next year, depending on water-testing data submitted by year-end from the state’s community water systems, schools and child care centers. Those results will indicate how frequently “elevated PFAS (occur) in drinking water and whether to recommend adding PFAS to the list of chemicals that should be routinely/periodically tested for,” said CDC spokesperson Robert Long.

Prospective homebuyers face another hurdle, since no labs in Maine analyze water samples for PFAS. Samples collected in Maine are shipped to out-of-state labs that typically provide results in two to three weeks, whereas the allotted time for house inspections is often just one week, said Rebecca Labranche, laboratory director for the state-accredited A&L Laboratory in Auburn. To speed up the response time for all those needing to sample water for PFAS, the state has allocated $3.2 million to help Maine laboratories “increase capacity for sample testing and analysis of PFAS,” Madore wrote, but the first grantees may not be ready to analyze samples for “at least a year.”

The Renys have considered selling their home, but even with full disclosure of the water contamination, she said, “the burden is so great we don’t want to pass it on to someone else.” They ultimately decided that to “stand our ground and deal with the situation is morally the right thing,” he observed.

But contending with PFAS concerns year after year takes a huge toll; “it wears on your mental state a lot,” Troy Reny said. The peace of mind they once had in this serene, hilltop setting is shattered.

“Home is supposed to be your safe place,” Ashley Reny said. “Coming home every day, I don’t know if it’s making me sick.”

Losing confidence in food safety

Fairfield residents now have similar anxieties about food. Households that have relied on their own farm animals, gardens and hunting have had to make an abrupt shift in those traditional practices, with advice to discard frozen venison and — for households with high PFAS contamination — even home-preserved foods.

Lawrence and Penny Higgins have lived for 29 years in a home near the Kennebec River where they raise alpacas and chickens. On a farm across the road, an overgrown sludge stockpile still sits as an ever-present reminder of how their artesian well came to be contaminated with PFAS. Since the state first tested the well two years ago, the PFAS level (for the six compounds tested) has doubled — for reasons no one can explain.

Their chickens, which once free-ranged, are now confined to a patch of soil that has tested clean. But even with filtered water and clean soil, the birds lay eggs with elevated PFAS in summer (another mystery that might be solved as more research is done on the effects of wind-blown dust from sludge-spread fields).

The Maine CDC tests the eggs every three months but lab results take another three months — making the data of limited use to the Higginses in deciding when the eggs might be safe to eat. Frustrated by the uncertainty of “now you can eat them, now you can’t, we might only eat a couple eggs a month,” Penny Higgins said. In so many ways, she added, “we live in limbo constantly.”

At one time, the couple raised nearly everything from their garden, she said, but the list of vegetables has shrunk to those – like tomatoes and potatoes – that the Maine CDC has informed them appear least likely to take up PFAS into the edible portions.

Knowing how little PFAS food testing has been done, Lawrence Higgins no longer hunts deer. The Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife has a deer consumption advisory posted for Fairfield, based on levels found in five of the eight deer initially tested.

Even choices at the supermarket now are daunting, Penny Higgins added. “And what about the farmers’ markets around here? I don’t know what’s safe to eat anymore.”

Occupational exposure

Other PFAS exposure concerns center on work settings such as fire stations, paper mills, clothing manufacturers and retailers, auto detailing shops, semiconductor plants, wastewater treatment plants, compost facilities, landfills and — where sludge was spread — farms. Even offices and schools may have high PFAS exposure, one study showed, if stain-resistant carpeting generates extensive PFAS-laden dust.

RELATED: How to reduce your PFAS body burden

In higher-risk occupational settings, there’s a dearth of data on how workers are exposed, what kinds of PFAS are present, and what the health impacts might be. Absent that science, PFAS are rarely discussed.

Justin Shaw, president of Local 4-9 USW at the Sappi mill in Skowhegan, said there are “multiple, multiple different chemicals” in paper mills and “we get pretty good training on how to work around (them).” But in terms of PFAS, “that’s an outside-the-mill term” that has not been covered in any chemical safety modules.

Until recent years, ski wax technicians used some formulas containing PFAS — scraping off old compounds and heating the wax to temperatures that generated abundant smoke. After years spent as a race director waxing skis in trailers with poor ventilation, Roger Knight, now team and wax manager at Portland’s Boulder Nordic Sport East, said he began wearing gloves and a respirator and advising others to do the same “just on the basis of a personal risk assessment, figuring none of us know really what’s in there.” Now it’s clear to him that the teams of chemists at wax companies likely did recognize the risks long ago. Knowing “what’s floating around in my bloodstream” after three decades in the industry, he added, “I wish they had done more to protect me.”

Despite Maine “making leaps and bounds” in advancing PFAS policies, the neglect of workers’ potential exposure “feels like a gap and oversight,” said Dana Colihan, co-founder of the community action nonprofit Slingshot. “People don’t really want to look into it.”

The Maine Department of Labor’s Workplace Safety Division, in response to an interview request, wrote through its spokesperson Jessica Picard: “While we cover hazardous chemical substitution in our hazard communication training class, the Department does not specifically cover PFAS in our workforce training at this time.”

The federal Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) has a New England regional office of Cooperative and State Programs, but it “does not have training, studies or grants related to PFAS,” wrote Edmund Fitzgerald, an OSHA spokesperson. Nor does OSHA have a specific standard requiring employers to institute engineering controls or work practices to minimize employees’ PFAS exposure.

The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), at the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) “is not aware of current training resources being developed specific to PFAS for workplaces,” said Scott Pauley, a CDC press officer.

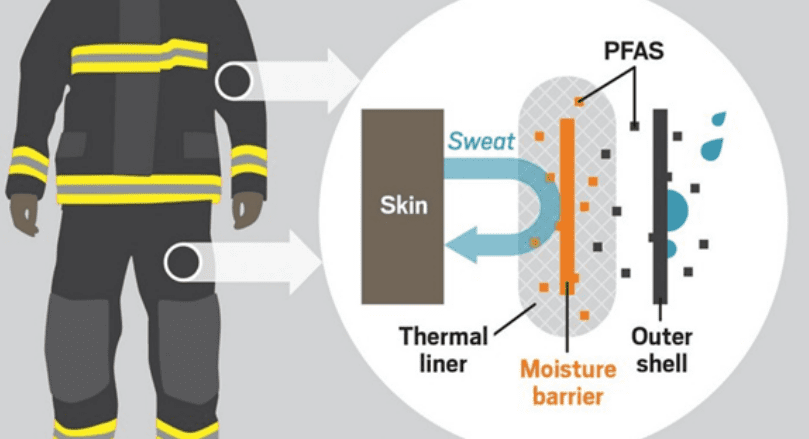

NIOSH is trying to lay the groundwork for workplace training by studying worker populations, developing analytic methods to better test workplace exposure and determining the best means for potential intervention. Research is just starting on workers in “manufacturing settings where PFAS is used or integrated into products” and in service sectors, Pauley wrote, and extensive research is underway on PFAS exposure and health indicators among firefighters.

That study began in part due to pressure from Portsmouth, New Hampshire, firefighters, who sought follow-up to a multi-year NIOSH study that found firefighters had a 9 percent higher chance of being diagnosed with cancer than the general U.S. population. Russell Osgood, chief of the Ogunquit Fire Department and vice president of education for the national Firefighter Cancer Support Network, formerly served as a firefighter in Portsmouth, where he faced PFAS exposure both in firefighting and from drinking water contaminated by firefighting foam (AFFF) at the former Pease Air Force Base.

Awareness has grown over the years about the PFAS hazards associated with structural fires and AFFF, he said, and “the discussion has really blown up” recently — in part due to a 2020 study that showed PFAS throughout firefighters’ protective (turnout) gear.

AFFF use is largely banned in Maine, but there’s no quick fix to the risks inherent in turnout gear, Osgood noted, since few manufacturers have begun producing PFAS-free gear and replacement costs could run about $6,000 per set. He hopes that federal or state grant funding might help departments with the changeover.

In his work to educate firefighters about toxic exposure, he said, “we talk about modifiable risk factors a lot,” urging people to eat right, exercise and do wellness checks — since “you do have control over that. As for PFAS, we can’t control that right now.”

First responders are left to bear this burden when “it all starts with the chemical industry having free rein to pump this into our environment unchecked,” he said. “It shouldn’t be that way.”

‘There’s nothing we can do for you’

For the growing number of Mainers confronting significant PFAS exposure concerns, lack of medical understanding and support can add stress. Even the most studied PFAS compounds are not well understood, and they represent only dozens among more than 12,000 distinct PFAS.

Scientists and medical researchers are scrambling to learn more, but that can leave those with high exposure feeling like medical “guinea pigs,” one Fairfield resident observed.

Even doctors well versed in PFAS health threats can offer little more than monitoring to those who have had significant exposure. Hearing from your doctor “there’s nothing we can do for you,’’ said Troy Reny of Fairfield, “those words crush you.”

People are left waiting and watching for symptoms, knowing that exposure could manifest in a long and growing list of illnesses linked to PFAS exposure: numerous cancers, suppressed immune functioning, liver damage, decreased fertility and pregnancy complications, thyroid disease, asthma, increased cholesterol, and reduced vaccine response in children. PFAS chemicals endanger nearly every organ system in the body, according to Linda Birnbaum, former director of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences and the National Toxicology Program.

Where the greatest costs fall

Layered atop medical anxieties are concerns about the financial implications of PFAS contamination for homeowners and hard-hit communities. In state testing for the sum of six PFAS compounds, Fairfield has 167 wells over the Maine’s drinking water standard, more than half the state’s total of 323 wells tested as of November 1. Nearby towns such as Benton, Unity, Oakland and Albion also have many affected wells.

In Fairfield, it’s unclear how many households might ultimately need water filtration — an outlay that the DEP estimates at $3,500 to $7,000 depending on pretreatment needs, with another $8,000 or more required where a shed is needed to house the system. Routine monitoring and filter replacement can run another $1,000 to $2,000 annually. To date, numerous wells in the community have tested below the state standard but above the new federal drinking water advisory. Other wells fall outside the state’s designated sludge-spreading zones so don’t qualify for state testing or filtration installation, but may still have detectable PFAS levels.

Concerns about how long-term filtration costs might affect residents prompted Fairfield’s town council to explore possibilities for an extension of the Kennebec Water District’s public water main, adding more than 20 miles of pipe at a projected cost of $48 million.

The town sought grant funds and was committed to having the project not covered by taxpayers, town manager Michelle Flewelling said. The plan encountered resistance in part because some of those affected felt more confident in house-scale filtration systems and foresaw further expenses in the future, given the public water supply will likely need PFAS treatment as well.

The Kennebec Water District, which supplies Fairfield and four other communities, draws from China Lake, which has tested at levels between 7 and 10 ppt for the sum of six PFAS compounds. Its general manager, Roger Crouse, didn’t anticipate the need for any filtration until last June, he said, when — due to a change at EPA — “overnight a reading for one PFAS compound that had been well below the advisory level was 1,000 times higher.” The district moved quickly to undertake an engineering study assessing PFAS treatment options, which Crouse anticipates will run into “multiple millions of dollars.” Barring any grants, he added, “every cost has to be paid by ratepayers.”

In June, Fairfield voters turned down the water main extension, leaving the community uncertain about how people will access clean water long-term. “There is no Plan B,” Flewelling said. “We just don’t know what’s going to happen.”

That makes homeowners like Penny and Lawrence Higgins anxious about who will bear the long-term costs of monitoring and maintaining the activated carbon system the state installed. “Are they going to say you’re on your own?” she asked. “Where does that leave us?”

Owners also fear that the contamination will lower the resale values of their properties. Flewelling said real estate agents have not seen a decrease in sales or value to date, but some affected residents are frustrated that their tax assessments remain the same when they’re convinced the market values have fallen. PFAS contamination poses challenges for real estate appraisal, Randall Bell and Michael Tachovsky of Landmark Research Group wrote in Environmental Claims Journal, given dynamics such as the ongoing process of testing and increasingly strict standards for how much PFAS is permissible in drinking water.

Needing more than carbon filters

“From the 10,000-foot view, Fairfield and the surrounding communities are an environmental disaster,” said Nathan Saunders. It’s hard for people to recognize the severity of the crisis, though, because — in Ashley Reny’s words — “everything seems right from the outside.” One insidious aspect of PFAS chemicals is that they are invisible so even highly contaminated sites look perfectly normal.

The state has stepped in to test soils, waters and foods and to provide some water filtration, but it has offered affected residents little support for their trauma. In a 2018 study, Canadian sociologist Debra Davidson wrote that toxic contamination events can be particularly traumatic because of the “invisibility and ambiguity of threats” and “the absence of resources necessary for resolution and recovery.” The contamination is experienced, she wrote, as “violations of bodies, land, livestock and loved ones. Victims experienced complete upheaval in their beliefs, and for many their experiences with contamination, and fears of future exposure, dominate their lives.”

Residents of Fairfield, while relieved to have carbon filters to clean their water, spoke of wanting more from the state – in providing PFAS water tests and blood tests to all those who seek them, in supporting the mental health of affected families (through measures such as a support line or ombudsman), and in openly acknowledging the harm done by sludge-spreading and hearing directly at public meetings the questions and concerns of those whose lives have been upended. These measures would help, one resident said, “if there is any healing of our communities to be had.”

This project was produced with support from the Doris O’Donnell Innovations in Investigative Journalism Fellowship, awarded by the Center for Media Innovation at Point Park University in Pittsburgh, Pa.