The week before her 22nd birthday, Courtney Allen overdosed three times.

For a decade, she had struggled with poverty, trauma and addictions to alcohol, heroin, Ritalin and cocaine.

“I belonged more to the dead than the living,” she recalls.

On that February 2015 birthday morning, she woke to vague memories of a fight and the police arriving to quiet the disturbance. Courtney panicked and worried about what may have happened to her sons, Wyatt, 8, and Aimin, who was nearly 3. She ran to their room and found them watching TV. Their eyes were wide and their frightened expressions jolted Courtney awake.

“In that brief moment of clarity, I could see where it was going to end for them. I could see that they were going to end up being just like me. They had so much pain on their faces.”

On that bleak morning, Courtney knew she had to seek treatment.

She checked into an Augusta detox center while her sister called the Department of Health and Human Services, which placed her sons in state custody. Courtney’s boys would be counted among the 440 Maine children removed from their parents that year due to drug use.

I had a judge who didn’t judge me and a caseworker who believed in me. For the first time, someone asked me, ‘What do you want to do with your life?’ ”

— Courtney Allen, an Augusta mother celebrating three years of being drug-free

“The pain, the shame and the guilt,” Courtney remembers, “was excruciating.”

For the next year, she agreed to participate in the Augusta Family Treatment Drug Court, a civil court that assists parents who are working toward reuniting with their children. The court offered Courtney intensive counseling, daily sessions with a case manager, and biweekly appearances before a judge.

“I had a judge who didn’t judge me and a caseworker who believed in me,” she explains. “For the first time, someone asked me, ‘What do you want to do with your life?’ ”

Just shy of a year later, on Jan. 27, 2016, Courtney stood before a packed courtroom of family and friends as a judge reinstated her parental rights.

“In a way, it was more special than the day they were born,” she says. “Because I finally deserved to be their mom.”

A shining example of recovery and capacity to change

Nearly three years later, at age 25, Courtney is one of Maine’s most active and respected leaders in the recovery movement.

A role model at Family Treatment Drug Court, she now mentors parents who are battling addiction and face losing their children. A junior at the University of Maine majoring in justice advocacy and mental health, she has a 3.97 GPA and works at the college coaching students struggling with academics or substance-use disorders.

She has shared her story on state and national levels, created the Augusta chapter of Young People in Recovery, and co-founded James’ Place, a non-profit that offers affordable recovery housing.

“Courtney is a real hero in the recovery community and in family treatment court,” says Chris Deutsch, communications director with the National Association of Drug Court Professionals. “Her story is remarkable and important because it demonstrates the incredible capacity for human beings to change. Often the assumption is that people in the depths of an addiction or a mental-health disorder may never be able to recover, but Courtney is an example of why that’s not true.”

For many pregnant women or mothers in the early stages of recovery, Courtney represents hope. She understands the guilt, shame and stigma that shrouds addiction.

“A lot of us in drug court are relatively the same age and in the same situation,” explains Gabby, a mother who got hooked on heroin after losing her insurance and the ability to get prescriptions for painful health problems. “Courtney’s a role model, someone that shows we can fix things. We can get our lives back.”

A former mental health worker who asked that her last name not be used to protect her privacy, Gabby temporarily lost custody of her two sons to a relative while she sought treatment.

“Guilt and embarrassment are the hardest things,” she says, explaining that she went into recovery earlier this year. “But Courtney is not embarrassed; she puts her story out for everyone to see.”

When Courtney talks about how her addiction affected her sons, her voice is soft and sometimes breaks.

“I didn’t wake up one day and decide to hurt them,” she says. “I was supposed to give them the life I never had, but instead I re-created my own childhood.”

Like many people with substance-use disorders, her childhood was marred by havoc and trauma. After her parents divorced, she and her mother lived in Rockland, where her grandmother owned a home in a trailer park.

“My life was chaos,” she says. “My mother had a severe mental illness and abused substances in between her meds.”

I grew up in a family where substance abuse was handed down through the generations, like an old bicycle passed from cousin to cousin.”

— Courtney Allen

Courtney lived next door to other relatives, who she says also abused alcohol, pills and intravenous drugs.

With little supervision, she started smoking marijuana at age 10 and drinking at age 12. In her family, early substance abuse was not uncommon.

“I grew up in a family where substance abuse was handed down through the generations, like an old bicycle passed from cousin to cousin.”

An honor-roll student, Courtney dropped out of school in seventh grade. She and her mom were homeless when Courtney learned she was pregnant. She was 13.

“I wanted desperately to be a good mom,” Courtney says. “I wanted to give my boy everything I never received.”

Courtney and her mother moved in with a relative in Augusta. Months later, she gave birth to a healthy boy she named Wyatt. She worked three part-time jobs to pay bills, but within a few years she slipped back into drinking, which, she says, led to other substances like Vicodin and heroin.

She was 19 when she got pregnant again.

“I was terrified. I didn’t know how I was going to stop using.”

A nurse at the Augusta needle-exchange clinic told Courtney that her baby could die if she tried detoxing on her own while pregnant. To keep Courtney and her unborn child safe, a doctor prescribed counseling and medically assisted treatment. Like many pregnant women addicted to opiates, Courtney was placed on Subutex, a drug that staves off withdrawals and cravings.

“My life, my health got so much better,” she says.

Aimin was born healthy, and for the next two years, the Subutex helped her remain stable. She worked, took her boys to the beach, celebrated their birthdays and holidays. But her unresolved childhood trauma and the stress of raising two young boys grew overwhelming.

“I was in an abusive relationship and I was starting to get scared. I didn’t know how I was going to take care of my boys.”

She started drinking to ease her anxiety, and the alcohol again led to other substances. She began injecting prescription stimulants and cocaine.

Though many of her memories are hazy during her drug use, one still haunts Courtney. The week before she sought help at MaineGeneral’s detox center, she locked herself in the bathroom. Fresh track marks lined her arms and orange needle caps littered the floor. Her hands trembled as she tried unsuccessfully to find a vein.

Outside the door, her sons pleaded with her, “Mom … Mommmm … please come out.”

As she listened to their voices, Courtney thought about death. She had overdosed three times during the previous week and imagined herself dying on the bathroom floor.

“All I can think of is making the pain go away,” Courtney thought to herself. “The mental agony of who I have become is too much to bear. How have I become everything I never wanted to be?”

A new, hopeful life in ‘the Taj Mahal’

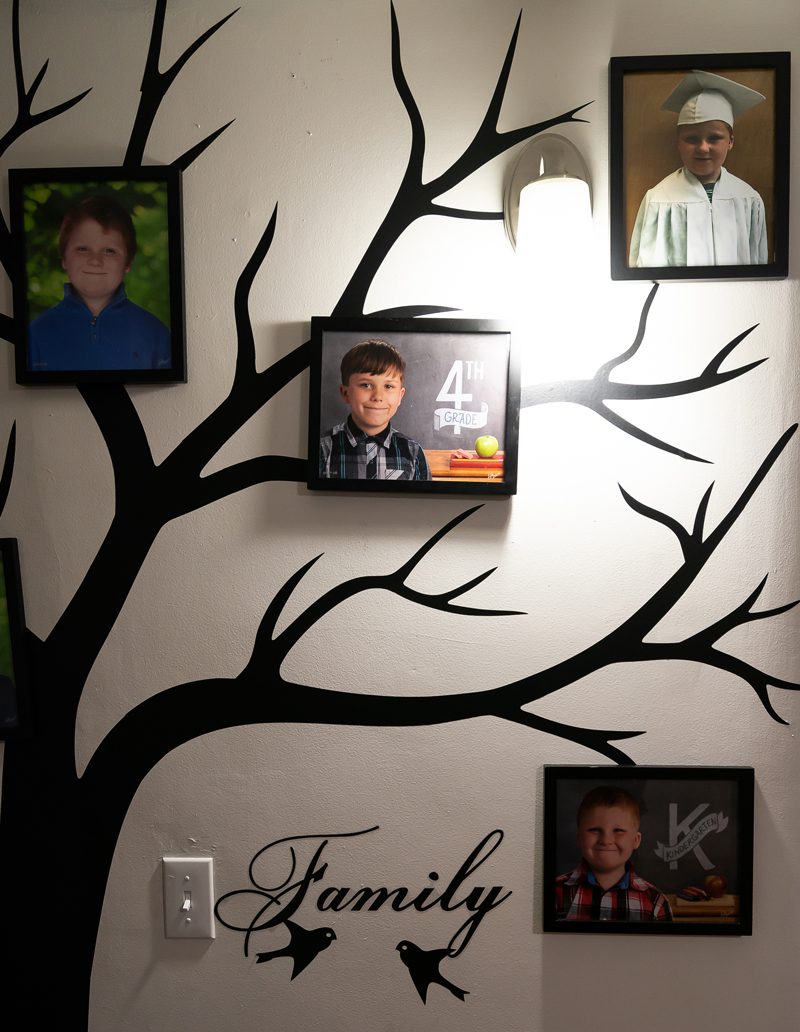

On a warm September afternoon, Courtney and her two sons – now 10 and 6 – unload their backpacks from the car and head into their new home. The rental house sits on a quiet dead-end street in Augusta. Courtney and her family moved in 10 days ago; a neighbor welcomed them with homemade pumpkin bread.

“It’s surreal,” Courtney says of living in the tidy three-bedroom home with a fenced-in backyard. “We moved from the ghetto to the Taj Mahal. It’s like how did we get here?”

She sits at a dining room table with her boys. A fifth-grader, Wyatt’s brown eyes are watchful, serious. His younger brother, a redhead with freckles, is quick to smile.

When Courtney asks Wyatt, “You remember me before recovery?” he pauses to think and then replies, “You were like oblivious, and you screamed a lot in general.”

“Not so much now,” Courtney says, her green eyes focused on her son’s face.

Too young to remember the years of his mother’s active addiction, Aimin climbs onto his mother’s lap and adds, “We love her.”

Today, the mother who once saw pain in her sons’ eyes now sees peace. In many ways, she is like any other mom cheering for Aimin at soccer games, helping Wyatt make posters for his Student Council election, taking her boys to beaches, apple picking, and on hikes through the woods.

“I am present, stable,” Courtney says as her boys disappear upstairs.

And she talks openly with her boys about her past and their future. She knows the trauma they experienced at a young age and that their parental substance abuse puts them at a higher risk for addiction. (Both of their fathers also were addicted to substances.)

“I’m trying to break the cycle,” she says.

To Courtney, that means less shaming and stigma, and creating a recovery community that offers support, housing, education and jobs.

“People want to stop using so bad, but it doesn’t happen right off,” she says. “When you leave the dominant culture and use, you’re labeled an abuser, a junkie, an addict; you’re alone and that’s where the recovery community needs to come in.”

Striving daily to build a community that cares about ‘her kind’

She holds fundraisers for food, clothing and shelter. She organizes family-fun days at the beach and at local parks for parents in recovery. And she is not afraid to ask business owners, churches and landlords like Kathleen Sikora for help.

“She is a force of nature, a force of social change,” says Sikora, who offered one of her apartments to be used as a sober recovery home within the James’ Place non-profit organization. “Courtney doesn’t wait when she wants something done; she just goes out and figures out how to get it accomplished.”

Courtney co-founded James’ Place this spring. It’s the first affordable recovery housing in Augusta – and is named in memory of her close friend James Reynolds, who died in 2017 of a diabetes-related illness. Courtney met Reynolds at a recovery meeting and was struck by his kindness.

“He had a huge heart,” Courtney says, “and was always ready to help someone in recovery.”

Funded by donations, James’ Place leases two apartments that offer shared living spaces for $425 a month per person. Residents sign contracts and must remain substance free, submit to random urine checks, participate in recovery meetings, and volunteer in the community.

But the six bedrooms are far from enough. Several times a week, Courtney receives phone calls from pregnant women or people who have recently completed detox programs or other treatment and are looking for a place to live.

“Every day, I have to tell someone I don’t have a bed for them,” she says. “It breaks my heart, and it makes no sense. From a taxpayer’s standpoint, we spend all this money on treating someone, and then they come out and they have to go back to the same environment they came from or worse.”

Courtney’s goal is to expand James’ Place through fundraising and finding more landlords willing to rent their properties.

“My hope is that no one would have to be turned away for recovery housing in the capital.”

The young woman who once imagined herself dying on the bathroom floor now lies awake imagining all the things she wants and needs to do.

At the top of the list is making amends to her sons, creating a home where they are safe and loved. And in between, she is pursuing her drug and alcohol counseling license and plans to apply to Harvard for her master’s degree in law or social policy.

“It’s been my dream,” she says, “to go there since I was a little girl.”