When Greg West received the alert for a motorcycle accident just after 2 a.m. last August, he dragged himself out of bed, then drove to the intersection of Stoddard Pond Road and Route 201 in Bowdoin.

He was the only member of Bowdoin Fire and Rescue to respond.

West, the deputy fire chief, found himself wearing “a lot of hats” at the scene. He was responsible for assessing the critically wounded driver, coordinating LifeFlight’s landing and commanding the emergency response.

Emergency personnel from Lisbon Emergency and Bowdoinham Fire Department arrived soon after, yet West was still juggling duties normally assigned to several people.

West and the other members of Bowdoin Fire and Rescue have grown accustomed to responding to emergencies on their own or with little help. As their list of volunteers dwindles, the remaining few members have increasingly shouldered the brunt of Bowdoin’s emergency response.

There is little evidence that Maine’s growing firefighter shortage has led to widespread department closures — at least, not yet. Instead, anecdotal accounts point to a proliferation of “ghost departments,” like Bowdoin’s, which operate with only a handful of responders.

No one knows how many fire departments in Maine are teetering on the edge. Ghost departments are active, but their ability to respond to emergencies is exceedingly limited, pointing to an unsettling possibility that the state’s firefighter shortage is even worse than officials think.

To respond to everyday incidents, these departments often rely on mutual aid partners for assistance, stretching neighboring personnel-strapped departments thin.

It’s not just fires. Firefighters are frequently the first and primary responders to a wide array of situations, especially in rural areas. They regularly deal with vehicle accidents, provide emergency medical care, clear blocked roadways, and staff search and rescue efforts.

Losing just one or two key members could leave these understaffed, volunteer fire departments with no choice but to close, eliminating crucial but often overlooked public resources.

Bowdoin Fire and Rescue has eight people on its call list, but just three of them accounted for 72% of the department’s responses this year.

When these members receive an alert, they face a stark reality: If they don’t go, it’s possible no one will.

This year, Bowdoin Fire and Rescue has been unable to respond to more than a quarter of the calls it has received.

‘Neighbors helping neighbors’

Longtime members of the department remember when Bowdoin’s fire station was bustling with members eager to serve.

Now, dozens of hooks on the fire station wall hang bare. Piles of donated water bottles and soda cans sit in the meeting room. It could be months, even years, before the volunteers use them all.

Eric Sheen has seen it all. He began serving with Bowdoin Fire and Rescue in 1988 when the department was just a year old.

Bowdoin residents formed the department “because we relied on Bowdoinham, and they were like us,” he said. “I mean, they had few guys, (old trucks), and it took them so long to get here.”

The fledgling fire company purchased its first engine, a 1956 Chevrolet, from Topsham for a nominal fee of $1.

The second truck wasn’t so easy to get. Sheen recalls four members of the department traveling to Ohio to drive the used 1977 Dodge back to Bowdoin.

It’s clear that Sheen is proud of Bowdoin Fire and Rescue’s 34 years of service. Twice he left the department — first for work in the New Hampshire woods, later for retirement — but it didn’t take him long to find his way back.

“All I do is drive the trucks now,” the 64-year-old said. “But just having a person on that truck that can … put water on fire and save a person, that’s an overwhelming feeling. You’re doing something for your community.”

Sheen and other Bowdoin Fire and Rescue members see their efforts as “neighbors helping neighbors.”

It makes the department’s current predicament even more difficult.

“I help my neighbors. They help me,” Sheen said. “Because I was taught that, that’s the way I was born and brought up … People just don’t want to work nowadays, and they don’t want to help people. They’re all about themselves.”

Out of ideas

In the last 15 years, Bowdoin Fire and Rescue has seen a steady drop in volunteers. When Tom Garrepy joined two decades ago, there were 40 members on the call list. Years later, when he became the fire chief, it had dropped to 30.

Then, in 2009, the Naval Air Station in Brunswick closed. Several members of the department were active Navy personnel and when the Navy left, so did they.

Members say it’s been a slow decline ever since. The last five years have been particularly tough, and COVID-19 made the situation even worse.

Garrepy said he expects the department will lose two more members after Maine’s vaccine mandate for healthcare workers goes into effect this month, leaving just six responders.

Last year, Garrepy went to Bowdoin’s board of selectmen to request funding to hire two per diem firefighters to help cover daytime calls.

The move would cost the town upward of $100,000, greater than the department’s current annual and capital budgets combined.

“They’re well aware of the staffing issues that we have,” he said. “They’re willing to do anything that I asked them to do if it helps bring people in.”

Still, the board declined to bring the proposal to taxpayers. According to Garrepy, the selectmen said it was too much money for a bedroom community of 3,100 to consider.

“The problem we’re running into is I think we’re out of ideas, I really do,” he said. We’ve tried the advertising, we’ve tried the school newsletter, we’ve tried local businesses and so forth.”

‘A total embarrassment’

Garrepy realized he needed more information to bring to the selectmen. Since the start of 2021, Garrepy and his crew have kept track of their response for each call they receive.

The results have been sobering.

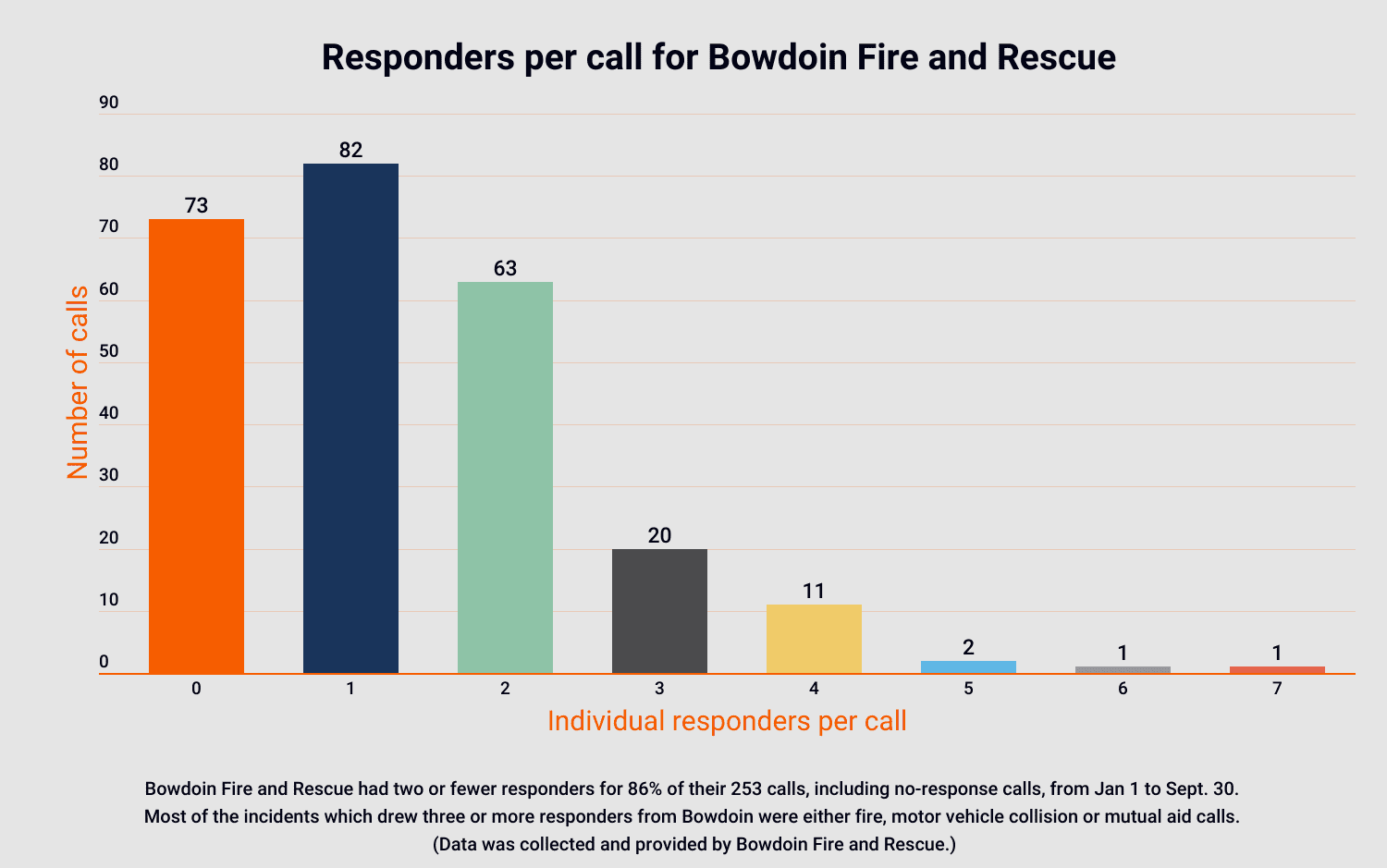

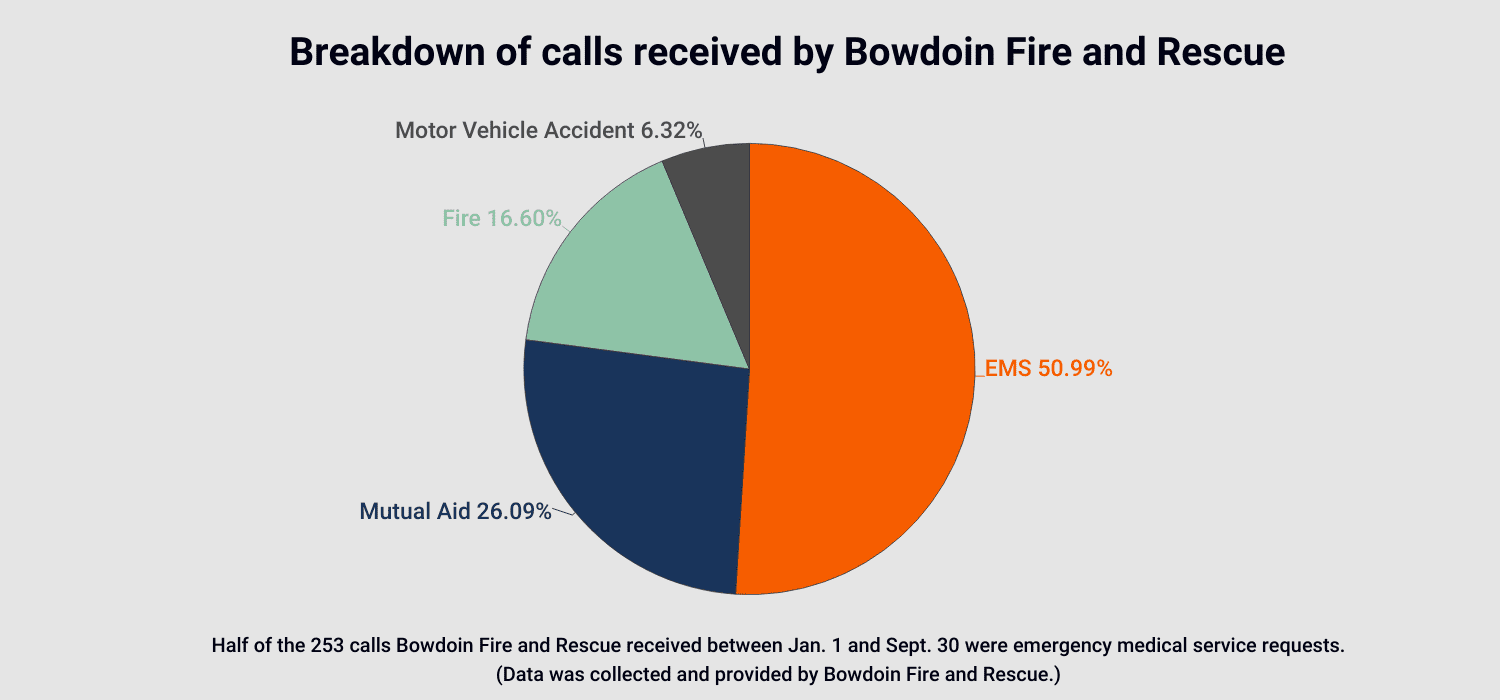

Members of Bowdoin Fire and Rescue were called for assistance 253 times from Jan. 1 to Sept. 30 of this year. Garrepy said the department normally has about 250 calls annually but is on track for a second straight record-breaking year.

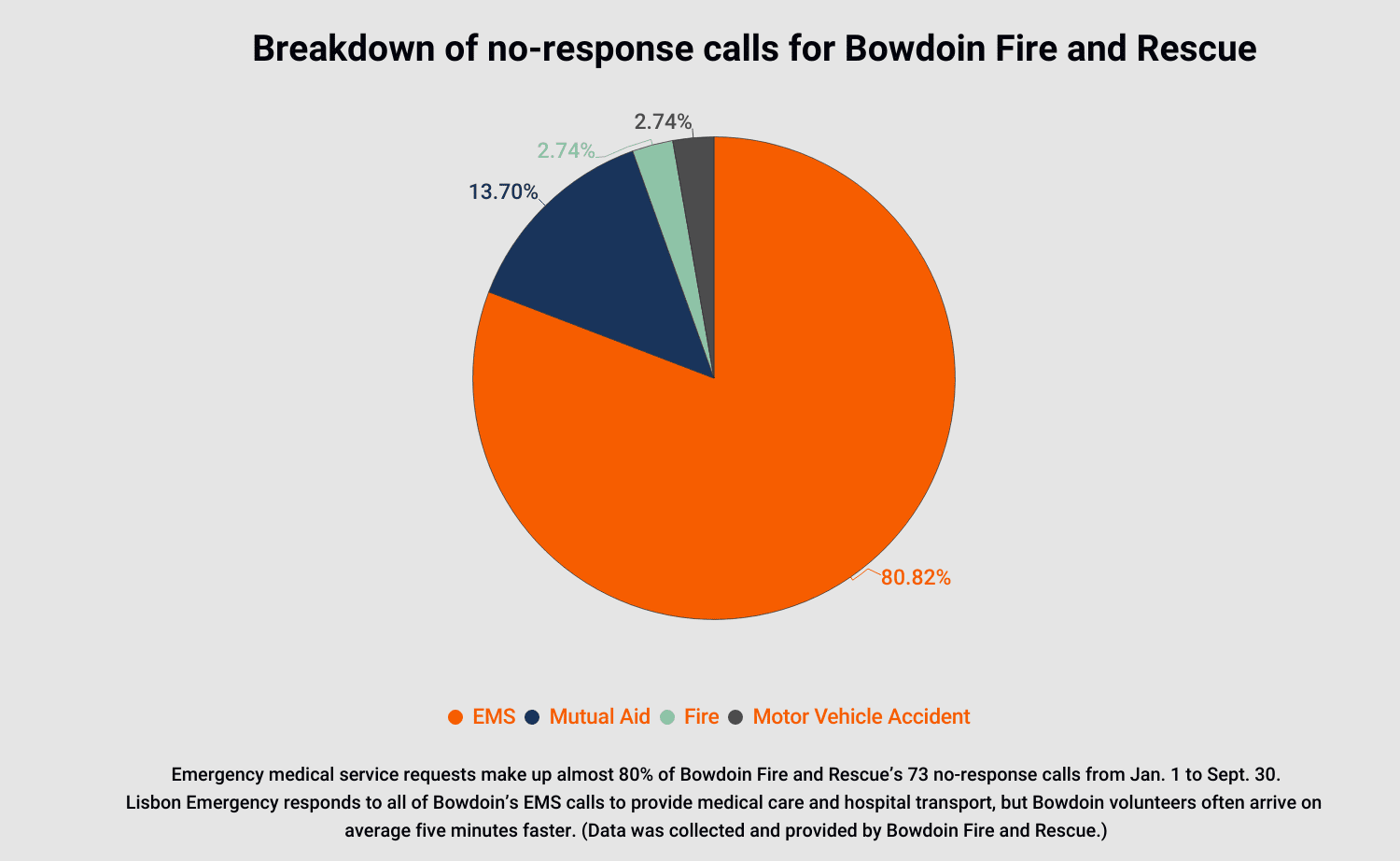

No one from Bowdoin Fire and Rescue was available to help with 73 calls this year.

Some 81% of the department’s no-response calls were requests for emergency medical service. Lisbon Emergency responds to these calls, and provides emergency care and hospital transport whether or not an emergency medical technician (EMT) from Bowdoin is available.

EMTs at Bowdoin Fire and Rescue are alerted because they often are able to respond faster than Lisbon Emergency, approximately five minutes faster on average.

In serious emergencies, such as sudden cardiac arrest, five minutes can mean the difference between life and death.

“I know I’ll have two people coming (from Lisbon), but that could be 12, 15 minutes away … If somebody’s in a life-threatening situation, four minutes can be a long time,” Garrepy said.

Another 13% of no-response calls were mutual aid requests. Assisting mutual aid partners is important. At least one department in Maine closed last year after a mutual aid agreement became one-sided.

Bowdoin is particularly reliant on its mutual aid partners, Bowdoinham and Richmond, due to the staffing shortage. According to department records, Bowdoin volunteers were unable to respond at all to two fire-related calls and two motor vehicle accidents. Mutual aid partners responded instead.

“I don’t think the townspeople really have an issue as long as they know that somebody’s coming. I find it a total embarrassment. I find it unacceptable that we cannot handle our own town,” said Garrepy, who noted that Bowdoin has handled situations for Richmond and Bowdoinham in the past.

Garrepy fears it will take a serious emergency — or even a death — before the community recognizes the severity of the department’s situation.

Memories in Thorndike

It’s eerie to walk through the Thorndike fire department.

Several handmade posters with photos of smiling children and firefighters hang on the walls in the meeting room. “Thank you Thorndike Vol. Fire Dept. from the ‘future volunteer firemen,’” reads a poster given to the department in 1992 by Unity and Knox Cub Scout troops.

The picture and helmet of a beloved former fire chief, now passed, is mounted above the chalkboard in remembrance.

Outdated gear is set against the walls of the garage. Some equipment no longer meets industry standards.

Piles of previously used turnout gear lay below a small plastic Christmas tree in storage, with dozens of boots neatly arranged on a table in the corner.

A pinboard covered with numerous patches from different fire departments sits on the floor, propped against a wall. The largest patch commemorates the fallen first responders of 9/11.

There are ghosts around every corner, on every wall. It’s not the past volunteers who haunt these departments, but the evidence of what the places once were.

Mass resignation

If Bowdoin’s volunteer firefighters disappeared with a whisper, Thorndike’s left with a bang.

In January 2019, four Waldo County emergency response officials wrote a letter to the town of Thorndike criticizing the department’s leadership and alleging its actions endangered the lives of other firefighters.

“We owe it to the residents of Thorndike and mutual aid towns to have trained and trustworthy first responders assisting them in their time of need,” the letter read.

At the time, the Thorndike fire department was not a municipal department but an association. Officers were elected by members of the fire company, but the town controlled their finances.

After the selectmen received the letter, the assistant fire chief, who was named as a concern for his leadership and past conduct, stepped down.

Department members felt he was unfairly targeted. They threatened to quit if the town refused to reinstate him, and release $85,000 from the association’s truck and equipment replacement fund to update the department.

When an agreement could not be reached at a contentious select board meeting in February of 2019, all but one of Thorndike’s 28 volunteer firefighters resigned, citing unsafe working conditions due to outdated equipment.

One month later, residents overwhelmingly voted to replace the Thorndike Volunteer Fire Company with a legally designated municipal department, giving the select board more control.

Second in command, now first

At 33, Thorndike’s interim fire chief, Tim Veazie, has faced more difficulties than most men his age.

Perhaps it’s these experiences that have given him the courage to lead a fire department others have abandoned.

Veazie grew up in the fire service. His father, aunt, and uncle were members of the Levant fire department in Maine. One of his earliest memories is a Christmas party at the old fire station.

As a teenager, he became a junior member of the department.

When he was 18, Veazie enlisted in the Army, then was deployed to Afghanistan in 2009. He returned to the U.S. nearly a year later after compounding incidents left him with permanent damage to his knees and back.

Veazie was medically retired in 2013 after 8 1/2 years of service. Like many other veterans, he struggled with homelessness and his mental health following separation from the military.

He moved to Thorndike with his wife and children in 2017, where he again found himself surrounded by firefighters. It took little convincing for him to join the department.

Two years later, Veazie resigned with the rest of Thorndike’s volunteer firefighters. He returned to the department six months later.

“Upon the town meeting, some of the requests that we had asked for, since they were making an effort on their part to get what needed to be done, done, then it was on us in order to keep our word and (return),” he said.

Veazie is the fourth Thorndike fire chief in two years. After the previous chief stepped down, Veazie, as the next highest-ranking member, became the interim chief in April.

No one else was willing to take on the role.

“I told the town that I will remain the fire chief for as long as they need me to be the fire chief, or until they find somebody better suited for the position,” he said. “I will, at that point, relinquish my position as chief, and I will step back into my shoes as second command.”

Veazie sees himself as the man leading men into the fire, not standing outside giving orders.

But with just five members and three firefighters, it may be a long time before he has the opportunity to do so.

To merge, or not

Earlier this year, the town of Thorndike approached Unity with the idea of merging their fire departments.

Under the proposal, Thorndike’s fire station would become a substation for the Unity department, and the town would pay Unity each year for coverage.

“It was, in my opinion, a last-resort solution used as the first option,” Veazie said.

According to Reginald Cunningham, a member of the town planning board and Thorndike fire department, the town did not go through with the merger for financial reasons. It would cost more to pay Unity to cover the town than retain its own volunteer fire department, he said.

While Selectman Jeff Trafton partially agreed, he said the situation was more complicated. The merger would have cost Thorndike more than the department’s current annual budget of roughly $35,000, but town residents would have benefited from improved service.

“Doing it the way we’re doing it now is cheaper, but I don’t want to continue doing it the way we’re doing it now,” he said. “We’re going to have to spend more money on fire protection.”

Trafton believes that regionalization is the future.

“Waldo County taxpayers are paying too much as a whole for their fire service,” he said. “If the towns could come together and form regional fire departments – it’s been done all across the country – we could all save money and we would all have service, 24/7.”

Can’t do without volunteer firefighters

As it is, the Thorndike fire department is barely hanging on. If it loses more than one or two of its five members, it will be forced to shut down, Veazie said.

“It would no longer be safe for us to try to operate as a fire department,” he added. “I am running with the five members that I have on my roster at the moment. I am running a bare-bones crew.”

Without mutual aid, the department would not be able to adequately respond to many calls, let alone serious emergencies.

“Thank God the other fire departments around us help us because if we have a house fire right now, we don’t have the manpower to fight (it). Those towns come over and help us for free,” Trafton said.

Recruitment is Thorndike’s primary concern, but replacing outdated equipment is a close second.

Thorndike plans to start paying firefighters $13 or $14 an hour to respond to emergency calls, similar to neighboring departments, Trafton said. Thorndike currently has a stipend system: Volunteers receive between $200 to $300 annually; the fire chief receives $3,000 and the assistant chief, $1,500.

Trafton and Vealzie hope payment will incentivize community members to join the department. The town is also working to purchase a new fire truck, a second initiative Trafton believes could encourage recruitment.