The local radio ad had a particular appeal as it played over the airwaves early this summer.

“We’re all trying our best to give you the service you expect and the vacation you’ve been wishing for, for the past couple of years,” the radio spot went. “Thanks so much for your understanding.”

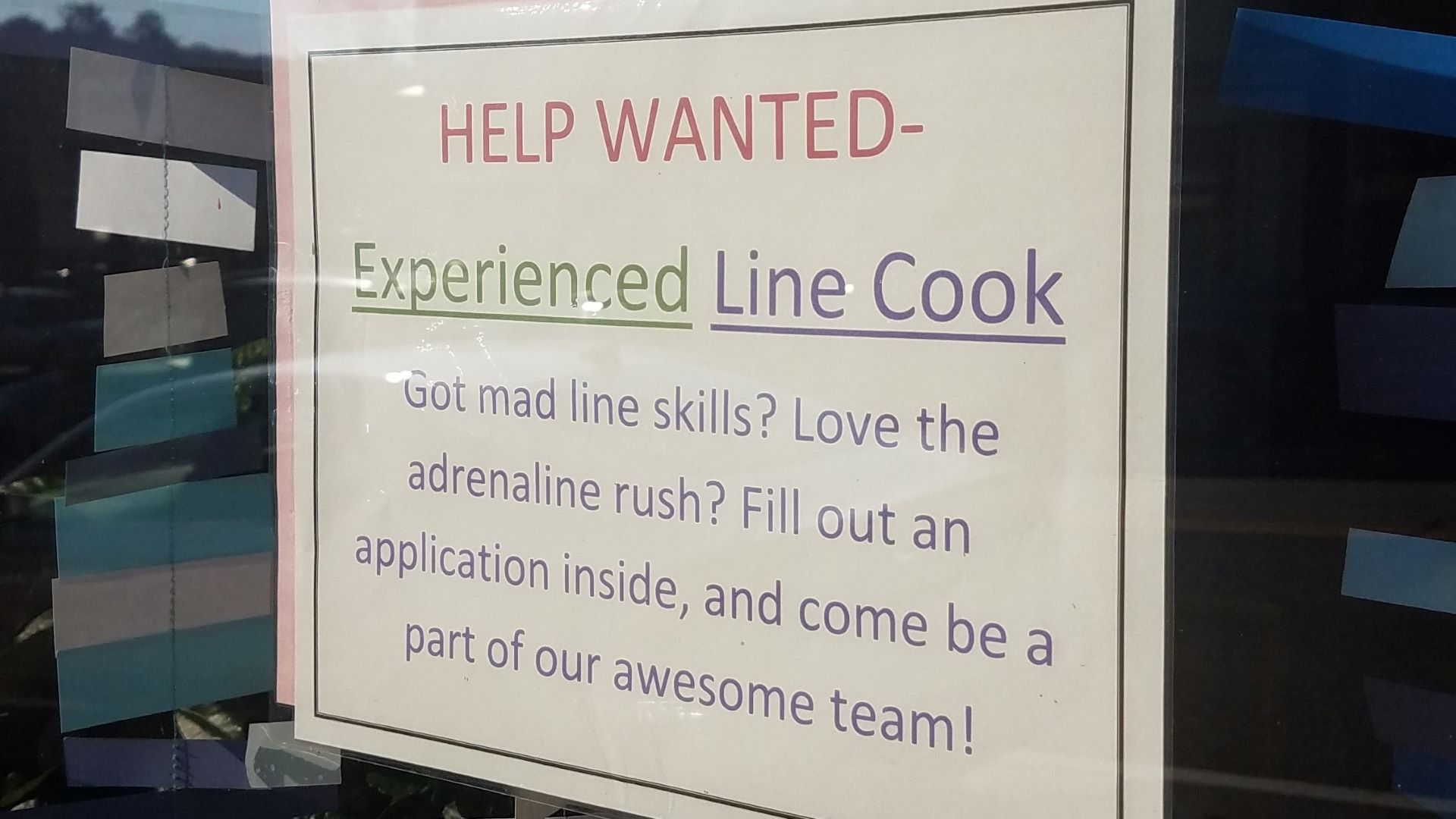

All across town, the point was driven home by the countless “Help Wanted” signs staked into grassy verges, lettered across bulletin boards and hanging in store windows.

This was Ellsworth, gateway to Down East Maine, as it braced for what would be a nonstop onslaught of tourists through September, largely fueled by visitors to Acadia National Park.

“(The 2021 tourism season) was absolutely a blow-the-doors-off record,” said Gretchen Wilson, executive director of the Ellsworth Area Chamber of Commerce.

In September alone, 667,392 visitors were recorded at Acadia, part of the 3.99 million visits through the first nine months of the year.

Wilson knew something was up when she began hearing early this year that campgrounds and bed and breakfasts were getting early reservations. People started coming during April vacation, she said. Bed and breakfast owners started saying in May and June they were booked through October.

But along with the tourist surge came a dearth of staff that swept through the hospitality industry.

It prompted Wilson to write a pair of ads to air on WNSX Star 97.7, an FM station in Ellsworth. She also created a “Be Kind” flyer distributed throughout the region, asking people to do just that — be kind — in the face of what would likely lie ahead: long lines, delays, and lodging and restaurant non-availabilities.

For Wilson, the writing was on the wall pre-COVID, in 2019, another big tourism year that showed a precarious labor situation. To manage post-COVID 2021, businesses would need more staff than they had in 2019. The new staff never came. Maine simply fell into a larger picture.

Nationally, the labor shortage has been in headlines for months as the pandemic continued, and it shows no signs of abating. The U.S. labor market has been buffeted from multiple directions:

● Resignations, averaging 4 million every month since the spring of 2021, and hitting 4.4 million in September (3% of the workforce), breaking August’s record of 4.3 million. The ongoing trend, chronicled by the U.S. Labor Department, gave 2021 a new nickname: the Great Resignation.

● Retirements, up to 3.6 million, way more than the 1.5 million expected between February 2020 and June 2021.

● Women leaving the workforce, and unappealing jobs, to care for children and/or other relatives.

● Fewer immigrant “guest worker” visas due to closed borders or delayed border openings.

● Increase in self-employment as COVID made people realize how fragile and short life really is.

At Manny’s Greek Grill in Ellsworth’s Mill Mall, the result in 2021 was not enough staff to handle the business.

“We were overwhelmed,” said Stacy Roguski, who owns the restaurant with her husband, Manny Kaminaris. “There just didn’t seem to be enough people who wanted to work.”

Manny’s has been a small establishment since opening in 2017, usually with three or four employees working each shift, including Kaminaris.

“When he’s not there, it’s closed,” said Roguski, who also teaches at Trenton Elementary School. Last summer, she and other family helped out, with a high school student and one other employee. There was “not a breath” to be had on Saturdays because they were so busy, Roguski said. Customers told them there was nowhere to eat in the area because other restaurants, facing their own staff shortages, limited their hours or closed on weekends.

Low pay, not enough housing

With the highest median age in the nation, Maine has its own hurdles.

Besides the struggle to fill jobs, there is an affordable-housing crisis, particularly in tourism-driven regions. The real estate frenzy, with homes selling at record rates and dollar amounts, has put even more strain on affordable housing – including homes where hospitality workers can live while they work.

Alarms about Maine’s demographic challenges have been going off for more than a decade, said John Dorrer, a labor economist who spent more than 40 years focused on Maine’s economy, labor market and work force. He was director of the Center for Workforce Research and Information in the Maine Department of Labor from 2004-11, and works at the national level, including previously as director of Labor Market Research at Jobs for the Future.

For 10 to 12 years, the evidence of slow population growth and an aging population has been well-known, Dorrer said.

“Few things other than demographics have as predictable consequences,” Dorrer said. “But as long as employers were getting by with established labor market practices, there was little attention given to future consequences.”

COVID-19 brought long-simmering vulnerabilities to a head. Dorrer said underinvestment in employment services and training assistance “stranded” low-wage workers.

“Furthermore,” he said, “wage stagnation over a prolonged period has held these same workers back at a time of growing income and wealth inequality. To a large degree, both our public policies, along with business policies and practices, have failed to give the needed attention to the low skill-low pay labor market that has now been exposed as ‘essential.’ ”

Dorrer said an opportunity to alter the state’s trajectory lies in the more than $4.5 billion of federal COVID relief funds coming to Maine.

“The key to charting new strategies will depend on strengthening the partnerships and relationships between the public and private sectors to get behind a ‘best for Maine’ approach,” he said. “This will require paying serious attention to sustainable funding of such strategies, and how we reform our tax structure to pay for the new ‘infrastructure.’ ”

It also will require a different message to students other than “go to college,” he said.

“We need to elevate the labor market literacy of students, parents and teachers so they can make better decisions about investing in their future. We need new forms of organization to represent the interests of workers. Unions served an important purpose but may no longer be the right vehicle.”

Looking at life differently

Matt Flynn, the owner of Express Employment Professionals in Portland, said he also saw labor issues before the pandemic.

“People aren’t as desperate as they were before,” Flynn said. They are looking at more than a paycheck when deciding where to work.

Employers need to show there is a benefit to working with them, said Flynn, whose company matches businesses with employees. “There are companies out there that are promoting the life balance thing. It’s got to be a two-way street.”

Greg Dugal, director of government affairs for Hospitality Maine, a nonprofit trade group, agreed the industry challenges — including housing, child care, retirements, wages and benefits — existed in a lesser degree in 2019.

“It is also a sizable demographic shift, which the prognosticators believed would be catastrophic,” Dugal said. “People like me are aging out of the workforce. It may or may not have occurred on its own, but the pandemic really added many additional wrinkles.”

Despite the hurdles, projections show 2021 will pass 2019’s $4.3 billion in taxable restaurant and lodging sales. But Dugal said the industry cannot sustain itself without strategies to address the problems.

“There is no question that guest worker programs and immigration reform are also key to the success of the American economy moving forward,” he said.

As the bulk of the summer and fall tourism season winds down, things are ramping up at winter hot spots.

Sugarloaf, like the Ellsworth region last spring, is seeing a spike in advance bookings.

“Our lodging reservations are pacing ahead of previous years, and advanced purchase of products like season passes, ticket packs and online lift tickets are pacing ahead as well,” said Ethan Austin, the resort’s director of marketing.

Austin said their employee numbers and job applicants are roughly on par with previous years. “Our workforce grows from about 250 in the summer to roughly 900 in the winter,” he said.

The growing challenge for Sugarloaf and the Carrabassett Valley region lies in housing.

“There have been significant changes to the local real estate and seasonal rental market over the past year and a half that have accelerated some challenges we were already seeing in regard to housing for seasonal staff,” Austin said.

The challenge snowballed with the pandemic.

“It is certainly playing into the staffing situation, and is something we are working hard to address,” Austin said. “There is a regional committee working on the issue that we are a part of, and we are working on plans to construct our own employee housing in the coming years. Currently we are working with numerous local property owners to help secure housing for our staff in various ways, including leases of local lodging properties for our staff, and even upfront seasonal rent payments to local landlords for our staff members.”