When the Maine Climate Council convened for an emergency meeting after destructive flooding across the state in December and January, they looked to a neighboring state for advice on resiliency.

Officials from Vermont spoke about their experience in July 2023, when as much as nine inches of rain fell on the Green Mountain State over two days, causing catastrophic flooding on par with Tropical Storm Irene in 2011.

Vermont’s lessons for Maine were all about flood management — clearing development and infrastructure out of floodplains to allow rivers to swell and ebb naturally without causing damage, for example.

Officials spoke about culvert and wetland restorations, which will help absorb and accommodate floodwaters from storms that scientists say are growing more intense as the planet warms.

Maine’s winter weather disasters this past season had major effects on the power grid, road infrastructure and working waterfronts, all of which were in focus at the Climate Council’s special meeting and in the advice from Vermont.

But what about the vulnerable infrastructure inside our homes and businesses? Just as they offer opportunities to “future-proof” roads, bridges and culverts, these increasingly common flood disasters could play a key role in the local energy transition as moments of mass need for climate-friendly improvements.

I spent the past several weeks talking to Vermonters about this for a story for Energy News Network.

“They’re ripping out drywall, they’re having to update systems — this is the time to make sure that you do it properly,” said Steve Casey, the supply chain engagement manager for Efficiency Vermont, a quasi-governmental efficiency utility that serves the state.

Just as Vermont saw better outcomes last summer for roads and bridges it upgraded after Irene, communities that had adopted rules to keep critical energy infrastructure out of home basements saw less of that damage, officials said.

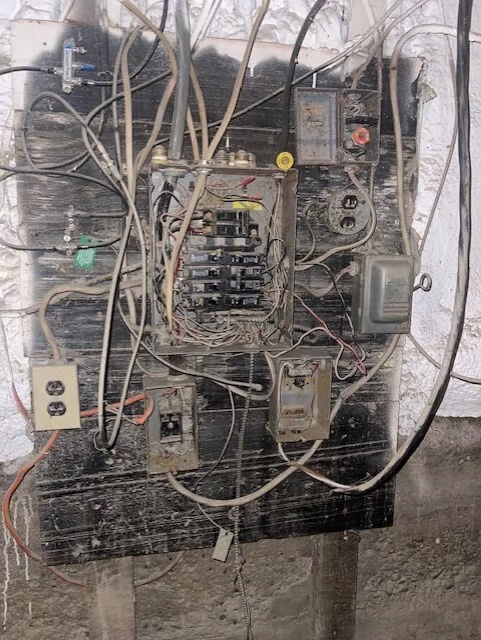

But this was not the norm. Many people lost electrical panels or heating systems and needed new ones. Yet Efficiency Vermont saw relatively slow uptake on the generous emergency rebates offered in the wake of the floods.

The challenges Vermont encountered in trying to prioritize energy upgrades in the wake of its disaster are some of the same obstacles facing this entire transition, especially for low-income people: a lack of up-front cash to cover projects before rebates; shortages of contractors and materials; a tangle of technologies, advice and aid programs that’s overwhelming even under the best of circumstances.

And these were not the best of circumstances. The winter heating season was fast-approaching in Vermont after the July floods. And unlike after Irene, there was very little spare housing stock where people could relocate.

“In 2023, July, people had to get into their homes as quickly as possible,” said Sue Minter, who leads Capstone Community Action in central Vermont. “You always have to have life and safety first…. (So) we couldn’t do the transition work (then), but that doesn’t mean we won’t.”

Minter was the deputy secretary of Vermont’s Agency of Transportation 13 years ago, when Irene hit the state with similar flooding to last summer’s disaster. As Vermont’s Irene recovery officer, she dealt with hundreds of miles of washed-out roads and bridges, federal disaster aid bureaucracy and more.

“Rebuilding a phone is not the same as rebuilding a bridge, because people’s lives are so impacted,” Minter said. But the principle is the same: “When you know you’re in an emergency, and you know everything has been destroyed, you also know it’s an opportunity to innovate … to rebuild differently.”

Now, Minter’s group and many partners, including Vermont utilities, are beginning a “phase two” of this work, literally revisiting affected homeowners they worked with last summer to circle back on their energy priorities.

It’s a post-disaster version of the social safety net and continuous support that seems required in this transition at every turn, especially in rural, low-income communities like Maine’s and Vermont’s.

“The households that are still in significant need at this stage were vulnerable households to begin with,” said Steve Casey. “We do have this repeating situation where flood events kind of just exacerbate some vulnerabilities for certain households.”

As Maine looks to become more resilient to similar disasters, it could take lessons from Vermont in this long view of energy upgrades as part of restoration.