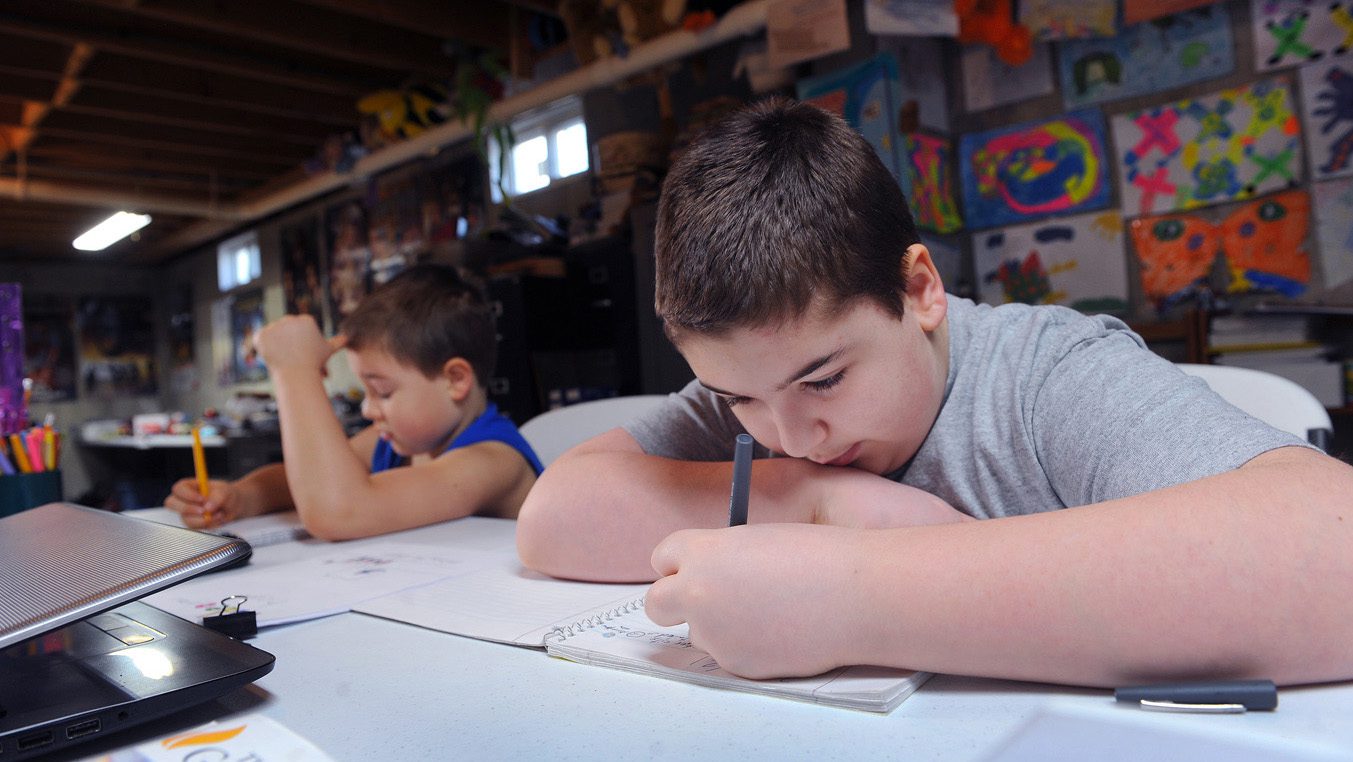

Fourth-grader Vaughn Hurd paced the floor of his basement in Morrill as he considered a math question posed by his mom, Angela. Stumped for a moment as he multiplied, Vaughn continued to walk in circles before triumphantly declaring, “72.”

“Good,” Angela Hurd said. Then she posed another equation.

“Just moving around helps me think,” Vaughn said. “In public school I couldn’t do that. I had to sit at a desk.”

Vaughn had been “begging” his mom to homeschool him for a couple years, but Hurd said she didn’t feel quite ready to take on the challenge. And she hoped her younger son, first-grader Sheridan, would remain in public school for a few more years so she could first adjust to homeschooling Vaughn.

Then the COVID-19 pandemic shuttered the doors of public schools, suddenly sending students home to learn from worksheets and Zoom lessons last March. Hurd, a former high school English teacher, said public school teachers did their best to make remote learning work, but the situation was “a disaster.” Teachers simplified lessons to avoid extra stress for students, Hurd said, but she worried her sons’ education would stall.

The experience convinced the Hurds to join the families of nearly 11,500 other Maine students who registered for homeschooling during the 2020-21 school year.

There’s been a roughly 71 percent increase in the number of recorded homeschool students this year compared to the previous school year, according to the Maine Department of Education.

Homeschool enrollment this year has been difficult for the agency to track, said spokeswoman Kelli Deveaux. Unlike previous years, parents have opted in and out of homeschooling since September as COVID-19 cases fluctuated. The Department of Education also moved to a virtual records system in 2019, and some families may have been duplicated or did not re-enroll in the new system that year, Deveaux said.

Officials are not yet sure what effect the rise of homeschooling will have on Maine students’ academic performances or whether it could change the state’s approach to education in the long term. But Hurd said she’s seen “huge growth” in her kids’ reading, comprehension and math skills. They do well on traditional testing and increasingly connect what they’ve learned to other materials or subjects.

Waldoboro resident Naomi McPhee said her two boys, ages 6 and 7, are much less stressed now that she is homeschooling them. She pulled them out of public school as soon as COVID-19 arrived because she didn’t think they would adapt well to the changes during the pandemic, which has killed more than 740 Mainers.

McPhee bases her teaching methods on what each boy likes to do. One loves to bake so she has him practice English while reading the recipe, science while learning about the ingredients and math while measuring each item. If the boys want to play outside, then it becomes gym class. Even a trip to the grocery store is an opportunity to practice adding prices.

“Every day when these kids do something, they’re learning,” McPhee said. “And they don’t need to sit down in a classroom with a book, especially if you have hands-on kiddos.”

The cost of leaving public schools

While the number of registered homeschool students in Maine shot up this year, the practice was gaining popularity before the pandemic. The number of registered homeschool students in Maine increased nearly 27 percent between 2016 and 2020, from 5,441 to 6,887.

During that time, public school enrollment declined less than 1 percent, from about 182,000 to 180,300. This fall, 8,000 fewer students enrolled, although they may not have all turned to homeschooling.

Public school may not be the right fit for kids who have special needs, health issues or don’t feel challenged enough, said Kathy Green, founder of Homeschoolers of Maine, a nonprofit that organizes resources, workshops and field trips. Often there are a number of reasons families consider homeschooling and COVID-19 may have been the “last straw” this year.

Some worry that if families continue to pull out of public schools, it could jeopardize state funding. To account for the impact of COVID-19 on student enrollment, Maine made a one-time adjustment to its funding formula for the 2021-22 school year. Kindergarten through fifth grade saw the greatest dip in enrollment, so the state lowered the elementary level student-to-teacher ratio used as a basis for its funding calculation. Lowering the ratio will give a bump in funding.

The greater concern is the societal impact of children leaving public school, according to Flynn Ross, an associate professor and chairwoman of the Teacher Education Department at the University of Southern Maine.

Academic performance can be “approximated” in homeschool, she said, but public school also provides students with social interaction, support for mental and physical health and exposure to new ideas.

“So on traditional standardized test scores, you may not see much difference,” Ross said. “But on higher-order thinking and understanding perspectives other than your own family, the impact can be tremendous.”

Ross said a lot of families contacted her over the summer asking if her students were available to tutor their children in a small pod. Most of those families were wealthy and had working parents struggling with the remote learning structure, but could hire private instructors, giving their kids an advantage and posing an equity challenge.

But Ross doesn’t expect the sharp increase in homeschooling to continue: “If anything, we’ve demonstrated (during COVID-19) how important in-person learning is.”

‘Meeting students in variable ways’

The Windham-Raymond school district experienced one of the state’s largest jumps in registered homeschooled kids, which increased from 47 to 129 this year, according to the Department of Education. That number could have been even higher if the school district hadn’t created an option for students to continue public school fully remote during the pandemic, according to Christine Hesler, the district’s director of curriculum, instruction and assessment.

Currently 351 kindergarten through eighth-grade students and 100 high school students are enrolled in the fully remote option. It was initially created to accommodate teachers who could not return to in-person instruction due to medical concerns around COVID-19.

Superintendents in other parts of the state, including Aroostook, Hancock and York counties, are finding success with similar programs, and are talking about ways to continue offering remote schooling even after the pandemic, said Deveaux, the Department of Education spokeswoman.

“It’s not just about the funding. It’s about the options and meeting students in some variable ways,” Deveaux said. “I think that this remote instruction option is one of those gems that are going to come out of this pandemic and remain.”

Maine received a $16.9 million innovation grant from the federal Department of Education to design examples of remote and hybrid instruction, including models that could continue after the pandemic.

In Windham-Raymond, they grouped kids by grade and taught the same curriculum as in-person but fully remote. Instructors also found creative ways to keep students engaged, such as building bridges and rollercoasters at home, Hesler said.

“It’s just hard because if you listen to the news, all you hear is remote education is failing,” Hesler said. “And yet these teachers have turned those students’ days into really a different experience than it was this spring. They’re having fun.”

Hesler said the district is already seeing some homeschool families “trickling back” to remote public school, and some remote families coming back into the hybrid model.

‘They were ready before I was’

The Hurds, however, plan to homeschool even after the pandemic. They’ll continue until at least middle school, but the boys say they want to homeschool straight through high school.

For Vaughn, the best part about homeschool is he’s never late to class. He only has to walk downstairs to begin his day.

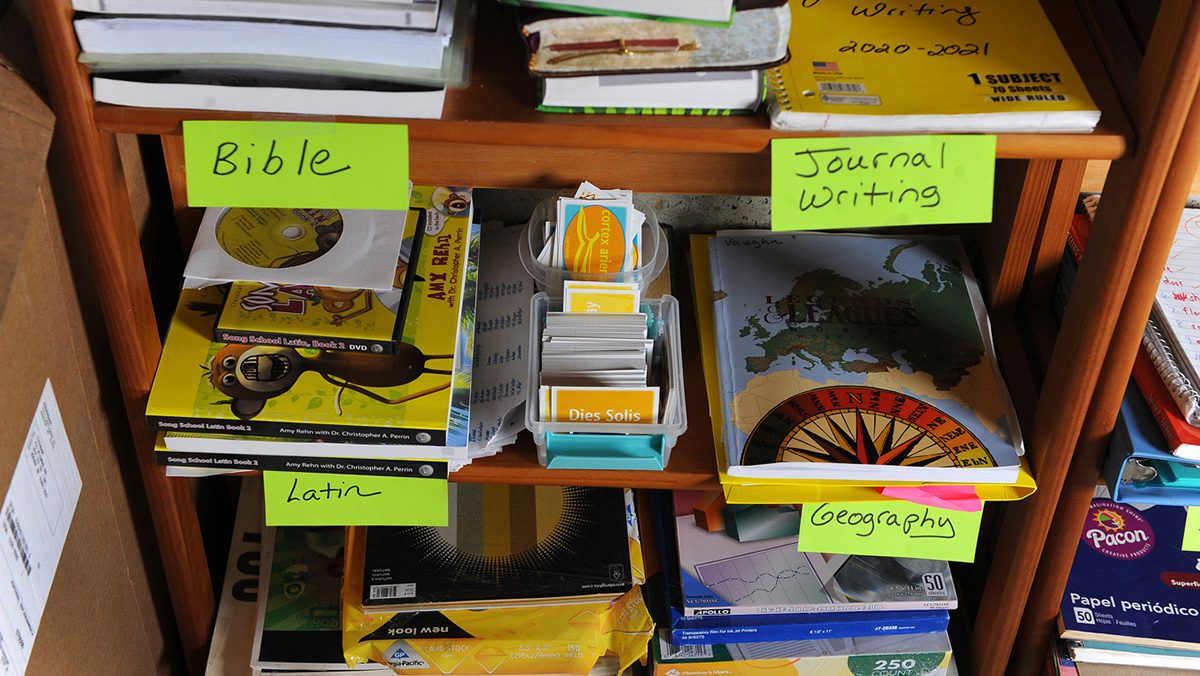

In many other ways, though, school in the Hurd household is structured similarly to public school. They follow a block schedule alternating on Green Days and White Days with half-hour and hour-long lessons in math, grammar, writing, penmanship, vocabulary, botany, Biblical literature, history, geography, Latin, human anatomy, reading, music and physical education. The boys do some lessons together and some independently.

A plywood wall in the Hurds’ basement is decorated with Latin words, posters of the human anatomy, maps, vocabulary words and drawings of historical figures like Justinian the Great and Johann Sebastian Bach. A red curtain divides the learning area from the play area, which is overflowing with Legos and trucks.

Vaughn said he likes homeschool because he doesn’t have to dwell on topics he already understands. Instead of being bound to the curriculum for a specific grade, “I get to move up and down levels,” he said.

Vaughn, 10, proudly displayed a picture book he made based on the videogame Minecraft and a stop-motion movie out of Legos. He aspires to become an engineer.

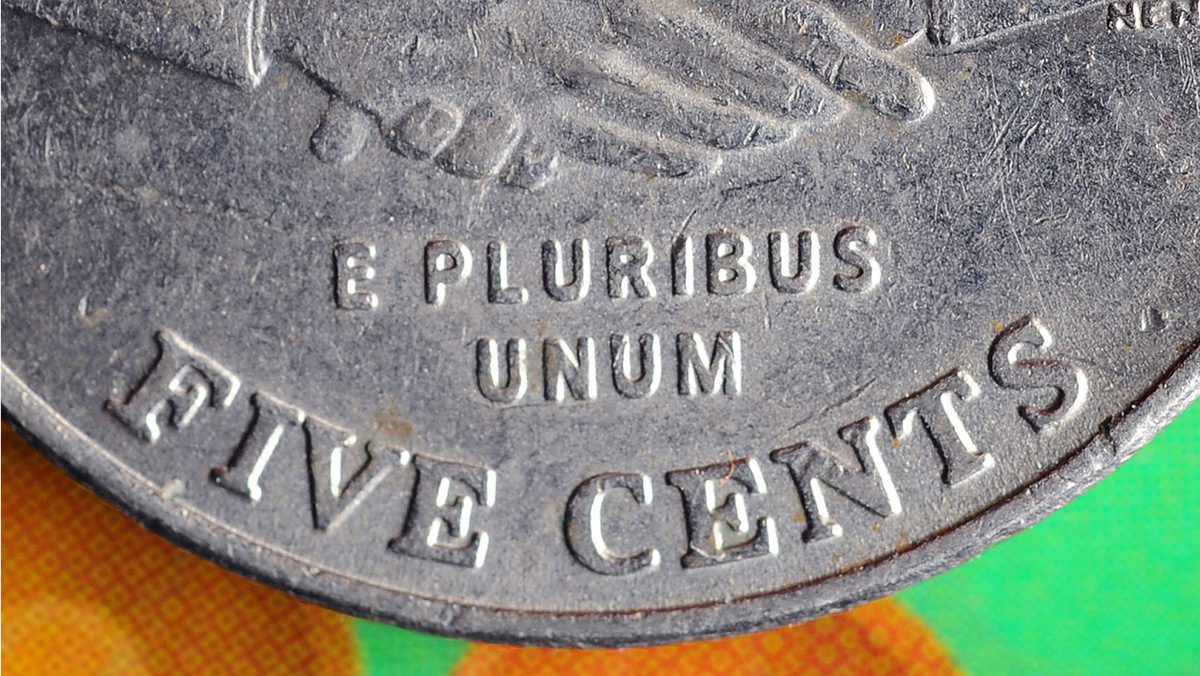

Sheridan, 7, reads novels and takes his spelling quizzes while sliding back and forth on a skateboard. He was excited to recognize the Latin he’d learned in the tiny inscribed words on a nickel: E pluribus unum. “Out of many, one,” he translated.

Hurd quit her job as an English teacher a year before the pandemic in part due to a medical issue but also because she was preparing to homeschool her kids. But she still was nervous to take on the job.

“They were ready before I was,” Hurd said.

She doesn’t see homeschooling as “an antithesis” of public education. Rather, there should be multiple options for schooling.

“I’m not anti-public education at all,” Hurd said. “I’m very much for public education. I think it’s a necessity for a civilized society.”

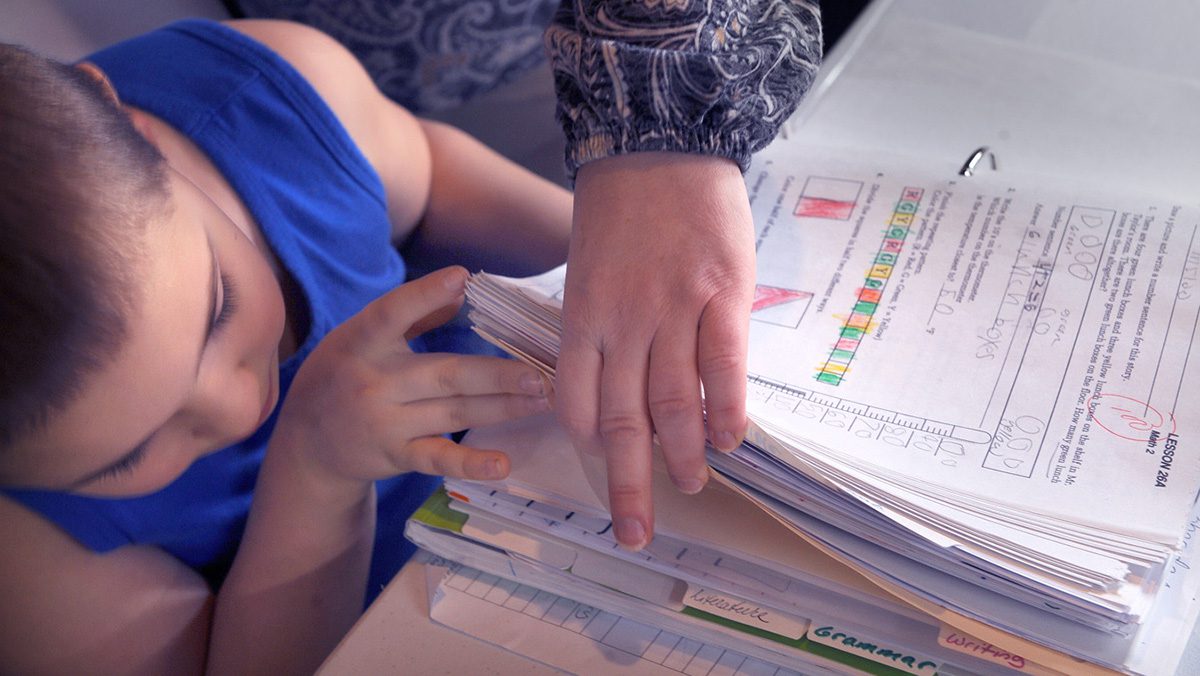

Sometimes she wonders whether she’s accomplishing anything. Then she looks at the boys’ portfolios and sees how far they’ve come in handwriting, sentence structure and history knowledge.

Just as she used to do as a teacher, Angela Hurd takes notes throughout the year on what works and what doesn’t. She’s confident next year will be even better: “This is my dry run for homeschool.”