Editor’s Note: The following story first appeared in The Maine Monitor’s free environmental newsletter, Climate Monitor, that is delivered to inboxes every Friday morning. Sign up for the free newsletter to get important environmental news by registering at this link.

The Kennebec River in Augusta and Hallowell saw near-record-high flooding earlier this week as inches of rain fell across Maine and New Hampshire.

According to the National Weather Service, the Kennebec crested at just over 20 feet at the downtown Augusta gauge early Tuesday morning. Social media posts, like the one pictured above, show how the swollen river overtopped its banks and spilled onto adjacent roads before starting to recede.

The Kennebec River gauge in neighboring Hallowell recorded a crest of 16.6 feet around the same time, well above the other highs on record in that spot (though this data is more limited, as this gauge does not have year-round forecasting).

“That flood in Hallowell was particularly impactful. Some water got into some first-floor buildings,” said meteorologist Jon Palmer in the NWS’s Gray office (check out Spectrum reporter Susan Cover’s photos of that flooding).

“Across Kennebec County — just a lot of high water, water in the floodplain, low-lying areas,” Palmer said. “(We had) 4-6 inches of rain overnight Sunday night. That’s a lot of rain for our area.”

Rain and river flooding, especially dangerous flash flooding, are inextricably linked, especially in developed places with more hard surfaces that don’t quickly absorb stormwater runoff. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration says on its severe weather basics page that flooding kills more people in the U.S. every year than tornadoes, hurricanes or lightning.

“Flash floods occur when heavy rainfall exceeds the ability of the ground to absorb it,” NOAA says. “They also occur when water fills normally dry creeks or streams or enough water accumulates for streams to overtop their banks, causing rapid rises of water in a short amount of time.”

It’s important to emphasize that no one weather event can be attributed to climate change without complex modeling to see whether it would have happened the same way in a world that didn’t have rising levels of greenhouse gas emissions trapping heat in the atmosphere.

But research does show that climate change is causing rainfall to increase in quantity and intensity across the country and especially in the Northeast.

“Further increases in rainfall intensity are expected (in the coming decades), with increases in precipitation expected during the winter and spring with little change in the summer,” scientists wrote in the Northeast chapter of the 2018 National Climate Assessment, or NCA. (The next installment in this series is due out this year.)

The Kennebec Journal’s editorial board took this up in the aftermath of this week’s rains, writing on Wednesday: “Like it or not, the climate crisis is coming. For those on the Maine coast and along our tidal rivers, it is already here. If we in Maine don’t do our part in limiting its effect on our communities, how can we ask anyone else to do theirs?”

Data from the Maine Climate Office shows that in 2022, the state saw nearly 8 inches more rain as compared to the average for the last century. The largest anomaly in increased rainfall has been recorded in the fall season.

Most of Western Maine got a month’s worth of rain in the past week, the NWS said on Twitter Thursday.

Increased temperatures cause more moisture in the air, but that’s not the only factor that drives spring river flooding. Maine’s shifting seasonal timing and snow patterns also play a role. In fact, per the NCA, an increasing pattern of earlier snowmelt and a shorter snow season may lead to lower spring stream flows, which could help mitigate flooding.

This ties in to the effects of the rain we saw this week. Palmer, the meteorologist, said this event’s relatively mild impacts are partly explained by its later-spring timing, which came after the bulk of the spring snowmelt.

“We did luck out that this happened now and not earlier in the spring, where we had a really deep snowpack. The impacts could have been significantly worse,” he said. “When you combine snowmelt on top of this amount of precipitation, that would probably prompt a lot of rivers to at least go into moderate (flood) stage and maybe into major stage too.”

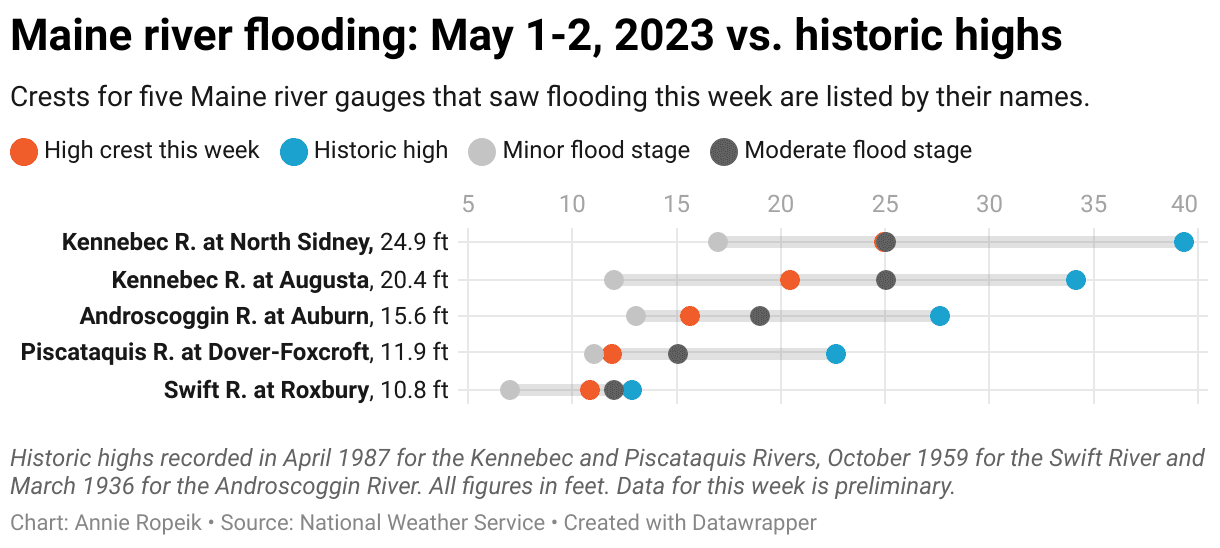

Many of Maine’s highest river levels on record came in spring 1987, an event fueled by a combination of rain and snowmelt, according to the NWS. Spring 1936 is another example, where high snowpack under a stalled rain system caused destructive ice jam floods and set records throughout New England.

In early March, the Maine River Flow Advisory Commission put out its annual assessment of these spring melt hazards — and found few to report. There was less river ice than normal for that time of year, said commission co-chair Nicholas Stasulis of the U.S. Geological Survey in a news release, owing to high stream flows in the fall and early winter and high temperatures in January.

RELATED: Storms expected to become more frequent, damaging as sea levels rise

Inland or coastal flooding at any time of year can wash out roads, overwhelm culverts and affect recreation infrastructure. Even New Hampshire’s Kancamagus Highway and the Mount Washington Auto Road took damage in this week’s heavy rain and, at those higher elevations, snow. Maine ATV trails will remain closed through Memorial Day thanks to the rain in an extension of mud season.

Floodwaters threaten people as well as infrastructure. Wardens rescued a woman from a half-submerged car along the Crooked River in Waterford as the rain fell on Monday night. Remember — turn around, don’t drown.

Maine’s 2020 climate plan said the state would seek federal approval this year for a climate-focused update to its Hazard Mitigation Plan. The climate resilience and infrastructure aspects in the climate plan itself focused largely on coastal flooding, including the official requirement that state construction projects plan for 1.5 feet of sea level rise by 2050 and 4 feet by 2100.

The climate plan also acknowledged the risks of riverine and rain-driven flooding places like Central Maine. The plan included expanded grant programs for fixing undersized and flood-prone culverts and creating other “climate-ready infrastructure” — a concept I covered a few years ago in New Hampshire, on a flood-prone salt marsh crossing I drove often.

In an update last December, the state highlighted a grant-funded stormwater overhaul slated for construction this year in flood-prone Winslow (page 51), which sits across the Kennebec River from Waterville. The state’s report said parts of the town, where the decades-old drainage system had “reached the end of its useful life,” were liable to flood in anything over 2 inches of rain per hour.

If you live near a stream crossing that frequently floods in heavy rains, check the list of state grants announced in March to upgrade undersized culverts. Flooding, as we’re seeing with these rain-driven river floods, is not just a coastal issue. More of these projects will be needed as Maine continues to get wetter.

To read the full edition of this newsletter, see Climate Monitor: Putting this week’s river flooding in context.

Reach Annie Ropeik with story ideas at: moc.l1751540774iamg@1751540774kiepo1751540774ra1751540774.