If you want to travel along the coast in Maine, you’ll more than likely have to traverse at least some of its muddy flats and brackish marshes, part of more than 150,000 acres of tidal wetlands that speckle the boundary between land and sea.

Crossing wetlands tends to be a mucky, messy business. That’s why, over the centuries, Mainers have built more than a thousand roads, bridges, railroads, dams and trails through and over them.

Increasingly, however, those crossings are running into a problem: 90% of them aren’t letting the tide ebb and flow and under them the way it should.

That’s creating a lot of issues for humans and the environment alike, altering the historical balance of saltwater and freshwater and putting low-lying roads at increased risk of flooding during storms and high tides.

“Wetlands provide significant ecosystem services,” said Jacob Aman, stewardship director at the Wells Reserve at Laudholm, “buffering against coastal storms and waves, protecting upland areas and developed areas, capturing floodwaters, capturing nutrients from polluted runoff.” They’re nurseries for baby lobsters, great at storing carbon, and a stopover point for migratory birds.

But without good tidal flow, both the infrastructure and the ecological functions in a marsh are at risk. That’s why, late last month, a group of more than 30 organizations, headed by the Department of Marine Resources’ Maine Coastal Program, released a 100-page long guide on how to make those tidal crossings more resilient.

The document occasionally veers into the technical but is still accessible, aimed at municipal staff, engineers, road owners and anyone else who’s “interested in helping to replace tidal road culverts and bridges with safe, climate-resilient crossings.”

The manual starts by explaining why wetlands are important (they blunt impact of waves, floods, and storms, stabilize shorelines, help maintain water quality, capture carbon, provide species habitats, and look beautiful, to name just a few) and then delves into how we’ve used them over time.

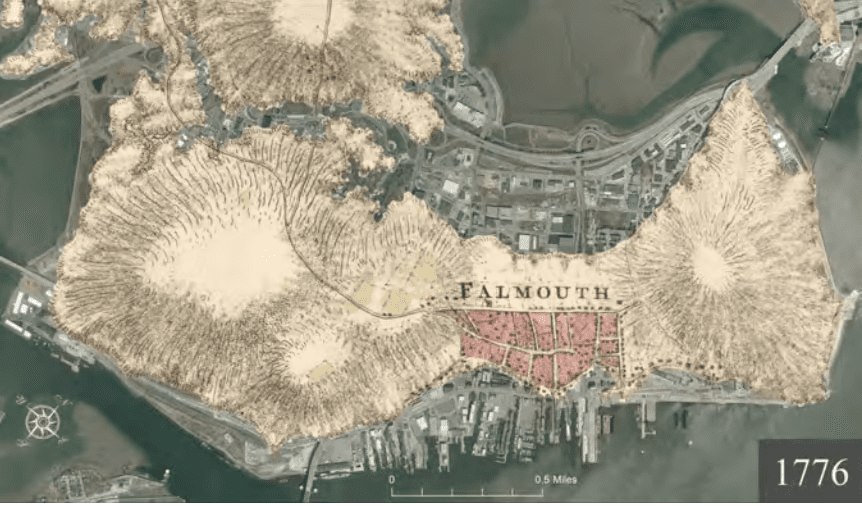

Maine’s coastal wetlands have been dammed, flooded, drained, farmed for hay, and filled; as far as scientists are aware, not a single one has been left untouched, said Tatia Bauer, a regional steward with Maine Coast Heritage Trust.

Much of the Portland peninsula, including nearly all of Commercial Street, was once wetland before being filled in in the 1850s. Those little wooden nubs you occasionally see in wetlands, like these ones in the Nonesuch River? They’re remnants of platforms for drying salt hay, one of the primary historical agricultural uses of the state’s tidal marshes.

As anyone who has ever had the joy of participating in a road association knows, roads are expensive to manage, even more so if they cross a place where the ocean was once and wants to be again. Most smaller culverts (spanning less than 10 feet) are owned and maintained by towns or private landowners. The Maine Department of Transportation is typically at least partially responsible for longer bridges, generally those over 20 feet.

The first step in managing a road that floods or blocks tidal flow to a marsh is to study it. Where does it flood? Where will it flood as sea levels rise? Does it lead to critical infrastructure, like a hospital, wastewater treatment plant, or power substation? It is the only access point? Does it provide access to other important community assets, like a working waterfront, schools, businesses, or residences? Is it part of a coastal evacuation route? What species are threatened by the inability of water to flow freely?

Any kind of changes should be done slowly and thoughtfully, said Jeremy Gabrielson, Senior Conservation and Community Planner at Maine Coast Heritage Trust, one of the organizations involved in the guide’s creation. It’s important to understand not just what’s under the bridge or culvert but also what’s upstream.

“If you change that tidal elevation too quickly it can have pretty significant impacts on upstream infrastructure,” he said.

The guidelines go above and beyond what’s necessary to meet state regulations, and are instead geared not only to making road crossings in wetlands safe and less prone to flooding, but also to ensuring the marshes, and the animals that live there, can thrive in a changing climate.

“The goal,” said Gabrielson, “is to design crossings in a way that’s going to be as ecologically responsive as possible.”