During the growing season, I periodically join a crew of volunteers on a local farm, harvesting crates of vegetables headed for food banks. It lifts our spirits knowing that all this beautiful, wholesome produce will reach the tables of those who need it.

But in our larger food system, 30 to 40 percent of what is produced never gets eaten. And all the resources that went into its growth — seeds, water, soil nutrients, energy, labor — are wasted too.

Eliminating this staggering loss could cut by half the number of Americans facing food insecurity. In Maine, where one in five children face hunger, it could transform untold lives.

The food wasted by consumers’ costs the average U.S. household an estimated $1,866 per year as of 2020, a figure that has undoubtedly risen due to the pandemic and increased oil prices.

Nearly all of the uneaten food ends up in landfills, where it can sit for two decades or more generating methane, a potent greenhouse gas. When climate impacts from production to disposal are measured, food waste accounts for 8 percent of global greenhouse emissions.

According to the scientific nonprofit Project Drawdown, cutting food waste is a top strategy to limit emissions. (Inexplicably, food waste got only a passing reference in Maine’s climate action plan, but it could still be added to the recommended community resilience actions that the state is supporting through grants.)

Redirecting food to hungry people would do far more than cut greenhouse gas emissions and increase food security. It would improve public health, save on municipal waste disposal costs, slow the expansion of landfills, and reduce water waste. With so many potential benefits and such universal relevance (everyone eats), tackling food waste should be a state priority.

The need for faster progress

When I first wrote about this topic in 2015, it seemed like the tide might be turning with the advent of composting businesses, the construction of an anaerobic digester in Exeter, movies like Just Eat It, a growing network of local food councils, and pilot programs in supermarkets to sell imperfect produce.

But then momentum seemed to flag. Some of those pilots ended, and other New England states moved ahead of Maine in crafting bans on landfill disposal of organic waste.

It’s hard to track how much progress Maine has made in recent years because the state lacks adequate staff to gather solid data on food use, diversion and disposal. The only reliable waste characterization studies date back to 2011, just before former Gov. Paul LePage abolished the State Planning Office. At that time, 27 percent of baggable household waste was food.

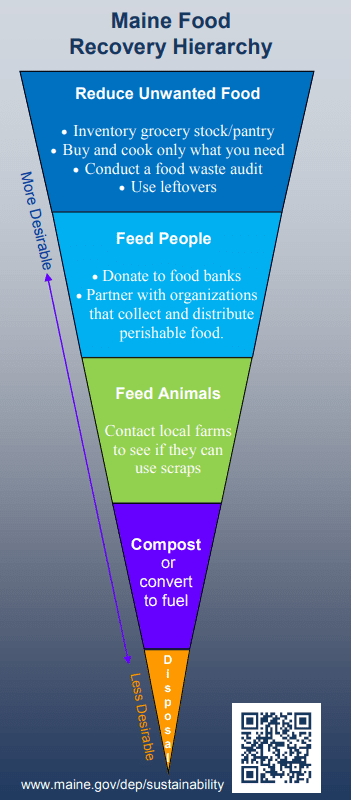

Almost no food should be landfilled or incinerated, according to the Maine Department of Environmental Protection’s food recovery hierarchy (see figure). The highest and best use of food is feeding hungry people. Animals are next, with inedible food scraps appropriate for composting or anaerobic digestion. The top tier of the pyramid deserves primary attention: preventing food waste (the proverbial “waste not, want not” tradition once revered in Maine).

Even diversion of once-edible food to anaerobic digestion “still represents a loss when compared to waste prevention,” said Travis Blackmer, an economist at the University of Maine, making the metrics of “success” in food waste reduction difficult to track. “Waste prevention is nearly impossible to measure in the aggregate,” he added, “so researchers focus on measuring what is diverted from disposal.”

According to Ryan Parker, Maine program associate director for FoodCorps, much of what is shipped to the anaerobic digester in Exeter is unopened, unused food that ought to be distributed locally to humans and livestock.

“It’s incredibly inefficient and makes zero sense,” he said. “We haven’t done anything to move things up to the higher levels of the (food recovery) hierarchy… The top tier is where we should be focusing.”

Susanne Lee, who leads Food Rescue MAINE — a program to end food waste established by the University of Maine’s Mitchell Center for Sustainability Solutions in 2019 — is working on that task and many others in collaboration with students, municipalities, businesses and nonprofits. They have identified a need for more food-processing infrastructure around Maine. In response, the university is developing a Maine Food System GIS map to help the state identify suitable processing locations.

Lee would also like to see Maine employ a widely used food rescue software system to help manage the dynamic mix of available food and volunteers willing to transport it. But any new approach, she noted, “needs to be community-based,” embraced by the volunteers who operate local food banks.

Building local resilience

Despite Maine’s thriving local food movement, little attention goes to returning food scraps to local soils — minimizing reliance on outside fertilizers and insulating communities from price shocks in waste hauling and disposal fees.

Skowhegan, for example, runs a municipal composting operation that gathers food scraps from local schools and residents to mix with yard waste. Bryan Belliveau, the town’s waste management supervisor, urges other communities to consider composting, given there are “only plusses to doing it; there are no negatives.”

Alongside generating compost valued at $40 to $60 per ton, municipalities could realize annual savings on waste disposal fees ranging from $5,000 per year for the smallest towns to $60,000 for cities like Augusta or Waterville, the Mitchell Center estimates. As hauling costs and fertilizer costs rise with higher fuel prices, the economics of local composting improve even more.

The Maine DEP offers grants for communities seeking to divert food waste, and U.S. Rep. Chellie Pingree has proposed federal bills that would provide grants for school and community initiatives to reduce food waste, and would create at the U.S. Department of Agriculture a grant and loan program supporting both large-scale and community-based composting.

To encourage more communities to reduce food waste and increase food recycling, the Mitchell Center’s Food Rescue MAINE will work this year with the Maine Department of Environmental Protection to offer regional meetings around the state. Details will be announced at a virtual Food Waste Solutions Summit on April 15. “There are so many factors that make now the time to embrace this approach,” Lee observed.

Revisioning food

Efforts like Food Rescue MAINE are helping, but the state needs policies to further accelerate progress. “Carrots and education aren’t going to fix the problem by themselves,” Parker observed.

Fortunately, states like Vermont have demonstrated viable models, like a food scraps ban, first applied to larger generators and then in 2020 extended to all households. The staged implementation gave Vermont time to scale up composting infrastructure and do the outreach needed to ensure broad voluntary compliance. As the ban took effect, food donations tripled.

Mainers, like residents of Vermont, value food equity, cost savings and healthy soils so there should be broad support for policies that reorient our food system to ensure edible food is consumed and scraps are used productively.

To get there, we need to recover more than just food. We must revive the ethic earlier generations had — recognizing that natural cycles are free of waste, and honoring food as the gift of a generous Earth.